By The Landlord

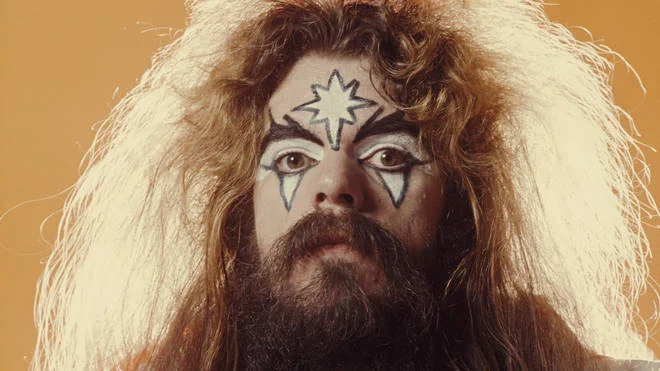

Birmingham’s legendary songwriter and outlandish performer Roy Wood from The Move, ELO and Wizzard walks into a smart tailors in the 1970s and says:

“Alroit, mate. I’d like nice, broit, culer-ful suit, please.”

The tailor responds: “Certainly sir, and would you like a kipper tie with that?”

Wood says: “Oh yis! Thanks mate. Milk ’n’ two sugars.”

It’s a well-known joke about this area of the West Midlands, and one I’ve told in the past, adapting it to Noddy Holder of Slade when introducing songs with regional accents, but this week, as previously on Manchester, we’re concentrating on one particular area of the UK, one marked not only by a particular accent, but by a vibrant cultural identity and a perky sense of humour hewn in the chimney smoke and struggles of heavy industry and engineering from Britain’s second city, a cornerstone of wealth and production. While the same, in a different way, could be said of Birmingham, Alabama, it’s the English city and its surrounding areas that applies, and our topic is not only songs by artists from it, but especially sought after are those about its places and history.

Perhaps some of the extra ingredients of songs from the area might also include local slang, such as cob for a roll of bread, fittle for food or snap for a meal; ackee (money); blarting (crying or sobbing); yampy (someone who is daft or mad); “going round the Wrekin” (to go on a roundabout route or tell a rambling story, named after the Shropshire hill); clarting about (messing around), wammel (mongrel dog, from the Anglo-Saxon hwaemelec), babby (baby, from babban), mithered (bothered) from mythered; wussa (as in was – ‘I ay wussa off’) from wyrsa; and the vividly messy “never in a rain of pigs pudding”, meaning something that will never happen.

Bostin’, meaning amazing, brilliant or excellent, is a word believed to come from Anglo-Saxon, bosten, something to boast about. And Birmingham can boast many other particular qualities in its wonderful cultural diversity and rich output of music, comedy, theatre and cuisine as the best place for a balti, bar none. Posh food too? It’s also home to more Michelin-starred restaurants than anywhere else in the UK outside London.

When we think of this region, metal and heavy rock spring to mind, but there is much more to source, from folk and classical to reggae and ska, punk, postpunk, pop, hip hop and soul, with artists ranging from The Beat to Black Sabbath, The Move, The Moody Blues, Traffic, Dexys Midnight Runners, ELO, Felt, Spencer Davis Group & Stevie Winwood, Joan Armatrading, Roland Gift, Steel Pulse, Laura Mvula, Mike Skinner, Ocean Colour Scene, The Nightingales, UB40 and more.

Just a few of the contrasting musical artists coming from Birmingham

But what area are we actual talking about? Aside from main city, The Black Country is an area that is subject to slightly differing interpretations. The phrase is thought to date from the 1840s, from the heavy soot from industry or the thick coal seam close to the surface of the land that has fuelled mines, iron foundries, glass factories, brickworks and steel mills. The Black Country covers the West Midlands to include the boroughs of Dudley, Sandwell, Walsall and Wolverhampton, though the latter is a bone of contention.

It certainly includes West Bromwich, Coseley, Oldbury, Blackheath, Cradley Heath, Old Hill, Bilston, Dudley, Tipton, Wednesfield and parts of Halesowen, Wednesbury and Walsall, but some traditionalists consider it not to include Wolverhampton, Stourbridge and Smethwick or what used to be known as Warley. But if it is defined by the coal mines, Wolverhampton did have an 18th-century shallow coal mine. Either way, it’s time to blow away the soot and smoke, and follow the pathways of those many canal waterways from this and see what music pipes up.

Victorian scenes of The Black Country

The Black Country, an inspiration for many musicians and songs, has a mixture of industrial sprawl, but also natural beauty. Here’s how is was described in Francis Brett Young, 1924 novel, Cold Harbour:

“And as we stood there, a curious thing happened: a kind of window opened in the rain, just as if a cloud had been hitched aside like a curtain, and in the space between we saw a landscape that took our breath away. The high ground along which the road ran fell away through a black, woody belt, and beyond it, for more miles than you can imagine, lay the whole basin of the Black Country, clear, amazingly clear, with innumerable smokestacks rising out of it like the merchant shipping of the world laid up in an estuary at low tide, each chimney flying a great pennant of smoke that blew away eastward by the wind, and the whole scene bleared by the light of a sulphurous sunset. No one need ever tell me again that the Black Country isn't beautiful. In all Shropshire and Radnor we'd seen nothing to touch it for vastness and savagery. And then this apocalyptic light! It was like a landscape of the end of the world, and, curiously enough, though men had built the chimneys and fired the furnaces that fed the smoke, you felt that the magnificence of the scene owed nothing to them. Its beauty was singularly inhuman and its terror – for it was terrible, you know – elemental. It made me wonder why you people who were born and bred there ever write about anything else.”

The Bullring Bull

But what about the city of Birmingham itself. my relatively limited experience, for me Birmingham is foremost a place of multiculturalism. The last time I visited the city centre, aside from walking through the Bullring shopping centre that mixes modern architecture alongside Victorian traditional buildings, the city hall with the space-age Selfridges, the biggest impression was how Asian, black and white British cultures appear more integrated than I’ve ever witnessed elsewhere. For example, during a festival procession of teenage dancers, it was was just as common to see white kids wearing traditional sarees and performing moves from Pakistan as vice versa. It makes a mockery of Donald Trump’s ignorance, when during his 2015 presidential campaign trail, he described Birmingham as an exclusive Muslim area, intimating it to be a hotbed for terrorists. What nonsense. Birmingham is a prime example of how British culture can be mutually enriching, and this heritage has expressed in the great musical output for decades.

Stewart Lee

Birmingham people, perhaps through a mixture of hardship and opportunities rising and falling, as well as cultural mix, generally possess a fantastic sense of humour. My favourite standup, Stewart Lee, was shaped by his upbringing in the area. “I grew up in Solihull, on the edge of what was then the Birmingham conurbation. It was a good place to write comedy from. I didn't feel allegiance to anything. I didn't have working-class pride or upper-class superiority.

Native Brummie Jasper Carrott’s jokes about the area meanwhile are often targeted at his the poor history of this football team, Birmingham City. “You lose some, you draw some.” Milton Jones meanwhile jokes about less than glamorous reality of working in this busy place. “Did you hear about the Brummie who fought in Vietnam? He kept getting flashbacks about being in Birmingham.”

They sell fridges …. Selfridges building in Birmingham city centre

Birmingham’s pop music industry particularly began to spring, as in many places in Britain, in the 1960s. Jim Capaldi, drummer with Traffic, described how in his upbringing how influences from elsewhere helped informed the city to created originality. “This kind of music was just hitting England, so we were getting this following in clubs in Birmingham just cause we were trying to do something different.”

Traffic is also a known to be a key feature of the city, with it’s iconic, although to me nightmarish road intersections, popularly known as Spaghetti Junction.

Spaghetti Junction

Yet the area has been inspiration to much literature. JRR Tolkien based much of his ideas for Lord Of The Rings on the city and its blackened surroundings, perhaps including those forges for the fires of Mordor, but in particular The Shire, home to the Hobbits was inspired by the fields and mill at Sarehole, plus Perrott’s Folly and the Waterworks Tower in Edgbaston along with the University of Birmingham’s illuminated clock tower are all landmarks that inspired his books.

Perrott’s Folly - inspiration to JRR Tolkien’s Lord Of The RIngs

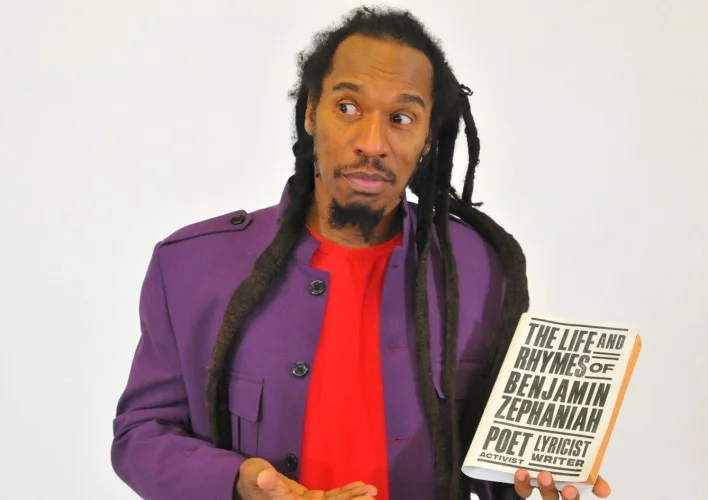

Other great literary notables, shaped in different ways by the city include David Lodge, Jim Crace, Roy Fisher and the poets WH Auden and Benjamin Zephaniah.

Benjamin Zephaniah

With its industrial history, Birmingham has also been home to many great movements and figures political insurgency, seeking workers’ rights in the face of exploitation. As Jim Crace put it. “The problems of the world are not going to be engaged with and solved in Faversham, they're going to be sorted out in cities like Birmingham.”

Most well-known and recently the city’s history has been captured in the gripping post-First World War TV drama series, Peaky Blinders, loosely based on a 19th-century real gang of criminals, who battle with the powers that be to control the city.

Peaky Blinders

But how will these week’s musical battles pan out? Keeping the peace, and placing a benign hand on the heavy industry of this week’s song nominations, I’m delighted to welcome this week’s guru, himself shaped in upbringing by the city, philipphilip99! Deadline for nominations is this coming Monday at last orders 11pm UK time, for playlists published on Wednesday. Alroit, give us a song now, will yow?

King Kong statue, Birmingham city centre, in the 1970s

New to comment? It is quick and easy. You just need to login to Disqus once. All is explained in About/FAQs ...

Fancy a turn behind the pumps at The Song Bar? Care to choose a playlist from songs nominated and write something about it? Then feel free to contact The Song Bar here, or try the usual email address. Also please follow us social media: Song Bar Twitter, Song Bar Facebook. Song Bar YouTube. Subscribe, follow and share.