By The Landlord

“If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow and the squirrel's heart beat, and we should die of that roar which lies on the other side of silence.” - George Eliot, Middlemarch

"These go up to 11 … that's one louder." – Nigel Tufnel, This is Spinal Tap

Ssshh! What is that noise? Is it the massive clang of snowflake landing on snowflake, the clattering landing and whooshing suck of butterfly kissing a buttercup, or the scream of sunlight across the sky? And what's that? Is it the raucous rushing wind of the internet? Or if you listen very carefully, can you hear the bouncy glide of elephants across the lawn, or the soft, feathery caress of a wrecking ball plunging into a wall?

This week, as I stack up the woofers and tweeters in the bar's backroom sound system, I'm stockpiling the earplugs, but also the ear trumpets. Because what we can hear is all relative. But in particular what we're listening out for this time are songs that are neither all loud nor all soft, but display a range of, and contrasts in volume, mastering the control of decibel and frequency, bringing subtlety and surprises to our ears.

How might that be achieved? Well, that's music that shows dynamic control, by either individual instruments or a voice varying its natural volume, or by the structure or production of a song taking us across a metaphorical mountainous landscape of sound, or a flat beach that suddenly dips underwater, or from a near-silent glade to a blaring metropolis of sound. Or vice versa and any number of times to create a shape that's far from linear. And this could cover any genre, from classical symphony to climaxing dance music, from emotional soul and gospel to rumbling reggae, from stop-start punk to theatrical pop.

The human ear can hear only up to around 120 decibels before sound really distorts and becomes unbearable, and 160 dB would tear your eardrum. And at the lowest end just about 0 dB, and RMS sound pressure of 20 micropascals. Eh? Can't quite catch that. But whether you listen to music soft or loud on your own volume control, it's the range within the music that counts.

But while our ears are a hair trigger to sounds, your hearing is only as good as the equipment you use too, isn't it? So shall we go shopping for some? This is a cracking little film. Want to hear the "sigh of the conductor as the piccolo misses its entry"? Here's how:

Now that's what I call the serious listener. Lovely work, chaps. However, is there a danger that chin-scratching concern over frequency ranges, crossover units and have a soft spot for a tweeter than can actually supersede music taste? And while home audio equipment was on the rise in the late 1950s and 1960s, the 1980s was the real decade for hi-fidelity, when far more than the specialist music enthusiast could as never before stock up on stacks on graphic equalisers and the like. But it could also be a little bit daunting, especially if you went into a shop, as we discover in this clip from Not The Nine O'Clock News, long before Rowan Atkinson became better known for Blackadder or Mr Bean:

Of course if you're looking to go the extra mile, or perhaps just one notch, there's always Nigel Tufnel's amps in This is Spinal Tap. Thats one louder. And don't forget, the sustain on that guitar. Listen to it. I can't hear anything:

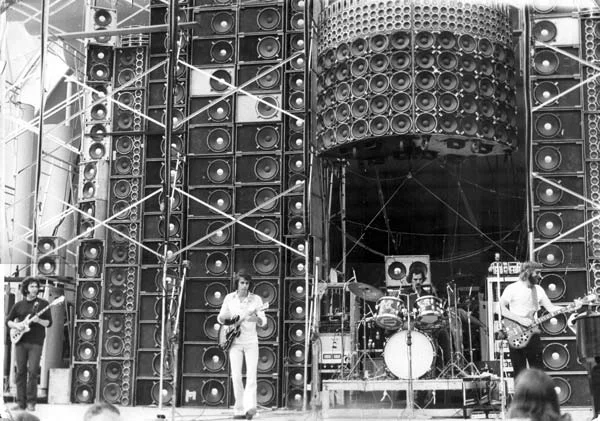

Or if that doesn't do the trick, how about the wall of sound created by The Grateful Dead in 1974:

Wall of sound: The Grateful Dead, 1974. Turn it up ...

There is much debate about which band has been the loudest in music history. From The Who to Deep Purple, Manowar to Kiss, Leftfield to My Bloody Valentine, some hitting a horrible 137db, it's all irrelevant. We all know it's Disaster Area from Douglas Adams's The Restaurant at the End of the Universe from The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy series. The audience listens from a specially-constructed concrete bunker some thirty miles from the stage, and the band plays its instruments by remote control from a spacecraft in orbit around the planet (or around a different planet).

Perhaps we should look more to the natural world about contrasting volumes than these intergalactic behemoths of rock. In the spectrum of hearing, humans are of course very limited, and we are merely minnows when it comes to creating sounds naturally. We’ve got nothing on the howler monkey, nor the greater bulldog bat, which has been recorded screaming at 140 dB as it hunts over lakes in Panama. Elephants’ rumbling can reach over 103db. The water boatman can produce 99 dB of sound by rubbing its penis across its abdomen. Handy!

Howler monkey

Snapping shrimps’ claws snap shut so fast they create a bubble with extremely low pressure. This means the bubble quickly bursts as it meets water outside it. When it does, it produces a shock wave measured at a whopping 200 dB. And who comes top. It’s not the blue whale, which can still call at the level of a jet engine at and ear-splitting 188 dB, but the sperm whale, whose clicks have been measured at 230 dB. A bit louder than your average click track.

But let’s take a more sensitive ear to hearing and remember that volume is also allied to frequency. From low to high sounds humans can generally on hear 20 to 20,000Hz, but cats, cows, ferrets, some dogs and porpoises much more, and bats and dolphins can hear up to 200,000Hz.

Shall we take a test? Put on your best headphones, and see if you can pick up any of these low rumblings:

How about this frequency range? Most of the higher stuff will be inaudible:

But now let’s take more perspectives on volume control with a series of guests now, as usual, visiting the bar. So to begin with, where is music going, is it getting louder or softer? “This is just the way it goes, says Suzi Quatro. “There's always a cycle with music – it goes up and it goes down, it goes risque and it goes back, it goes loud then it goes soft, then it goes rock and it goes pop.” Rock on, Suzi!

And here’s that deft Argentinian-Swedish indie folk singer-songwriter José González, known for his gentle, classical guitar playing, who reminds us that he used to be a hardcore rocker. “The music that I'm known for is quiet and gentle, although when I was growing up and as a teenager, I was playing the opposite - I was screaming and playing bass and those loud electric guitars.”

Meanwhile Depeche Mode’s Dave Gahan also calls for less loudness and more contrast: “I go to see some big shows of other bands, and I feel like I'm so bombarded and over-stimulated that I lose interest in the music. There has to be light and shade, and less stimulating moments. There has to be an arc to the show.”

But what about recording? Here’s the great songwriter and producer T Bone Burnett: "Record softly, and play back loud – and a whole other thing happens,” he advises, wisely.

Perhaps one way of finding songs for this week’s topic is to think of those that are best for testing speakers and headphones. The other week I met a representative of high-end audio specialist, Dynaudio, a Danish speaker maker that strives for such perfection that some of its products sell for tens, if not hundreds of thousands of euros. What music do they use to test for clients? Among others, one consistently reliable album is Lou Reed’s Berlin, I was told.

But now more bar guests arrive and they are taking us to other times and places and both these two prove that the power of the loud and quiet are just as important as each other. Here’s Oliver Wendell Holmes, the poet, physician and polymath: “The sound of a kiss is not so loud as that of a cannon, but its echo lasts a great deal longer.” But no one can follow the magnetic presence and undeniable authority of Catherine the Great, who has just swept into the bar with her entourage, has ordered the horses to be fed and watered, and demands several flagons of wine. I’ll get the vodka out too. “I like to praise and reward loudly, and to blame quietly.” Whatever you say, your majesty.

Finally though, let’s dip into some samples of potential music for this theme. On David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust album sleeve, the instruction is the “play at maximum volume”. Yet of course this doesn’t mean the music is all loud. In fact this masterpiece is full of volume contrasts, not easy to manage, but beautifully achieved. It Ain’t Easy, but he did it:

How about then also sampling the range and quality of a song performed by Esther Phillips, that not only does this, but also describes it in the title?

And finally, with the sudden, tragic and surprise news of the death of Chris Cornell, the frontman from Soundgarden and Audioslave, let’s listen to the appropriately named Black Hole Sun, for a song that shows extreme volume contrasts. Rest in peace.

So then, taking a turn, not only behind the bar, but also on the graphic equaliser and volume of this week’s playlists, I’m delighted to announce that we have a new guest controller. Please give a warm welcome to Rachel Courtney, aka uneasy listening, whose wonderful Philadelphia-based and topic-themed radio show can be found at uneasylistening.org. So get turning those knobs, put your music suggestions in comments below for the deadline 11pm UK time on Monday, in time for Rachel’s playlist to be published on Wednesday.

New to comment? It is quick and easy. You just need to login to Disqus once. All is explained in About/FAQs ...

Fancy a turn behind the pumps at The Song Bar? Care to choose a playlist from songs nominated and write something about it? Then feel free to contact The Song Bar here, or try the usual email address.