By The Landlord

"A story should have a beginning, a middle and an end, but not necessarily in that order." – Jean-Luc Godard

"The art and science of asking questions is the source of all knowledge." – Thomas Berger

"Who questions much, shall learn much, and retain much." – Francis Bacon

"Judge a man by his questions rather than his answers." – Voltaire

"The wise man doesn't give the right answers, he poses the right questions." – Claude Levi-Strauss

“I’ve found you’ve got to look back at the old things and see them in a new light.” – John Coltrane

"You have to ask these questions: who pays the piper, and what is valuable in this life?" – Robert Plant

"Who can it be now?" – Colin Hay

"Where is my mind?" – Black Francis

A very famous person has died, someone who made a wide impact. There's media attention, much reflection, thoughts about the past, mourning, commentary, meet-and-greet, handshakes and waving. But we're not talking about the late Queen Elizabeth II, who, while widely respected for her lengthy service, faithfully worked all of her life to maintain the status quo. Instead, another acclaimed nonagenarian died this month, a pioneer who by contrast did much to challenge and change the way we see and think about the world. And they were not constantly in front of the camera, but behind it – the French director Jean-Luc Godard (3 December 1930 - 13 September 2022). So instead of royal waves from limousines, he was a leading light in the French New Wave of cinema.

Old waves: Elizabeth, Charles, Anne, Philip …

New Wave: Godard and Truffaut

But how might this reflect on this week's song theme? French New Wave (La Nouvelle Vague) inspired many methods to re-shape creativity not only in film, but beyond, in art, writing and music. It began by challenging the establishment in its world, the standard Hollywood 1950s big-money machine of smooth, safe, uniform storytelling. It rebooted the genre with a variety of techniques, a low-budget, can-do attitude, and above all by addressing the viewer’s perceptions with a series of visual and other forms of question about what they are seeing and understanding. But how?

Most obviously it replaced the familiar with unconventional forms of shot, angle and editing (almost anti-editing) using jump cuts to story, vision, sound and continuity, challenging and confusing the viewer by omission as much as insertion, fracturing narratives, but still maintaining a compelling story by pushing its boundaries.

New Wave also added in the figure of the director as auteur, forcing us to recognise their individual style by visual delivery. It mixed fiction with documentary and added in freeze frame moments, and character asides to the camera. It also carried something of the candle of French existentialism, philosophy focused on the meaning, or meaningless of life, its ongoing absurdity in a world of change, mixed emotions, confusion but sometimes droll humour. And through all of these methods it asked lots of questions, often without supplying any answers. That was, and is, the whole point.

It's not difficult to see how such a compelling, creative approach and ideas helped inspire so much pop music in the 60s and the decades that followed, the new blood that sought to kick against the cigar-toting, all-controlling execs of a lazy industry. And of course this topic can include the musicians who made innovative, sometimes strange, sometimes beautiful, sometimes stop-start, jump-cut improvised jazz of the 50s era, music that often went hand in hand and became the soundtrack to French New Wave itself.

But more of that in a while. First, just to clarify, this topic is not about music under the term ‘new wave’, a confusing, nebulous umbrella term often used to cover a whole swath of releases in pop music in the 1970s and 80s, post-punk to electro- or synth-pop. While music of that era, as well as later or before, may come up and qualify as matching this topic lyrically or musically, it's more useful this week to turn our attention towards songs that enigmatically or entertainingly pose questions.

But first, let's have a taste of what the French New Wave actually did. It gradually came about from the growing number of small Parisian post-war ciné-clubs in the late 1940s, where figures including Godard and François Truffaut, Éric Rohmer, Jacques Rivette, and Claude Chabrol, as well as a the slightly less prominent group known as the Left Bank directors – Alain Resnais, Agnès Varda, Jacques Demy and Chris Marker all gathered ideas for their work.

Shoot the Pianist (Tirez sur le pianiste, Francois Truffaut1960, starring Charles Aznavour

These figures didn't dismiss American, British or other directors out of hand. They still admired and referenced the likes of Orson Welles, John Ford, Alfred Hitchcock and Nicholas Ray among others, but they were seeking their own visual voice, and also the escape the big studio influence and interference.

Key films include Truffaut's 1959 coming-of-age drama, The 400 Blows about a runaway Parisian boy, and his 1961 drama Jules et Jim, Resnais' 1959 Hiroshima mon amour about the relationship between a French actress and Japanese architect, one that opens with a shocking piece of documentary footage after the atomic bomb of 1945. But perhaps most of all Godard's stunning debut and masterpiece, 1960's Breathless, or À bout de souffle, starring Jean Seberg and Jean-Paul Belmondo playing a young American woman and a restless French criminal rebel obsessed with trying to be like Humphrey Bogart. All of these films contain many innovative techniques constantly asking questions about reality, love, perception and existence.

But don't take my word for it, here's some more useful analysis clips from these and other films:

French New Wave didn't just influence pop music, it also of course influenced many other great non-French film directors, including Martin Scorsese, one of the greats who inextricably merges image with sound too.

And here's Scorsese himself on the influence of, for example, Jules et Jim:

While some music from the era of New Wave, of or even the soundtrack of these films might potentially qualify, this topic is pushing boundaries with questions. so songs related might come from any era. In 1961 Truffaut said that "the 'New Wave' is neither a movement, nor a school, nor a group, it's a quality." So you might want to start with the likes of film score composers Paul Misraki or Louis Malle, but also the American musicians who inspired them too, such as Miles Davis, John Coltrane and Bill Evans.

Jeanne Moreau with Miles Davis

Charlie Parker

But if challenging 50s and 60s jazz isn’t your bag, there are other ways to address this topic, simply by nominating songs that are all about questions in lyrics, plot or structure.

So then, there's a lot of chin scratching, wine pouring and coffee drinking in the Bar this week, as many tricky existential and other questions are posed. First, here's more from Godard and Truffaut, leading the debate:

Godard mischievously makes statements that deliberately serve to make others question them. “Every edit is a lie,” he says, but that’s because he prefers not to edit in the conventional sense.

But on the other hand, “Photography is truth. The cinema is truth twenty-four times per second,” so that’s where editing, or anti-editing can reveal more.

“Art attracts us only by what it reveals of our most secret self,” he adds. His art, his medium, is cinema, but again it’s double-edged as a world of everything and nothing. "I know nothing of life except through the cinema,” he offers, and yet “Cinema is the most beautiful fraud in the world.”

Questions, contractions, and difficulties, that’s always the pattern, far more than answers. “I prefer to work when there are people against whom I have to struggle,” he adds, and that’s a tension he needs, and yet he acknowledges another contradiction. “Well, I pity the French Cinema because it has no money. I pity the American Cinema because it has no ideas,” he says, with a smile.

And Truffaut is no less filled with mischief and paradox. “To be a film-maker, you are almost forced to be surrounded by contradictions... You must have talents of so many different kinds - talents that are contradictory.”

Here’s one mixing documentary as well as feature: “In love, women are professionals, men are amateurs.”

Perhaps that tension in the creative process comes from the clashing of egos not only between others, but within oneself. “Taste is a result of a thousand distastes.”

Truffaut’s prediction of his art form seemed to be incredibly prescient when it comes to the social media generation of the 21st century, those whose film, or indeed music careers are formed through the medium of YouTube or TikTok:

“The film of tomorrow will resemble the person who made it, and the number of spectators will be proportional to the number of friends the director has.”

Actor Edward Norton is also here, feeling in awe of these two cinematic giants. “The best films of any kind, narrative or documentary, provoke questions.”

The poet WH Auden broadens the topic by adding that “history is, strictly speaking, the study of questions.”

And Song Bar regular Albert Einstein says the same of science. “To raise new questions, new possibilities, to regard old problems from a new angle, requires creative imagination and marks real advance in science.”

But how might songs nominated raise questions? The easiest option might be to pick out titles and lyrics with phrases that include or suggest question marks, but that alone would be too formulaic. The song must also have an unanswered, or difficult-to-answer question implicit or explicit within it, or a series of questions running though its seam and theme, rather than just a planted phrase. What’s going on? How soon is now? Where did our love go? Three well-known examples, but are you still left with the this and even more questions unanswered? Bonus points for strange, humorous or highly original questions too.

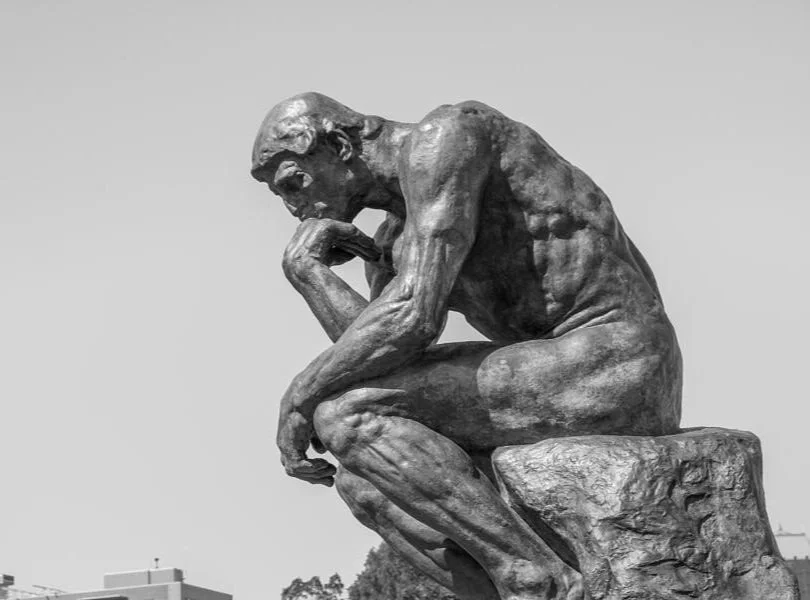

God or dog? Existentialists gather to ponder the big questions

Or indeed, another side of this topic might be works in which the music itself asks questions, structured or edited in a way to express that probing attitude, such as with sudden changes of pace, or key, or style, that in turn echo the French New Wave style of challenging the audience with unconventional forms and perceptions. There are many ways to interpret this.

Here’s innovative rapper Mos Def, commenting on the contractions and struggles between his interests and an industry that constantly moves towards a more commercial, non-creative direction.

“I can't control what people think. I'm not trying to manipulate people's thoughts or sentiments. I write all the time. You have to experience life, make observations, and ask questions. It's machine-like how things are run now in hip-hop, and my ambitions are different.”

But let’s close with two greats of the cinema and jazz worlds, echoing each other in asking questions of themselves and their audience:

More or less, I am always saying, ‘Give me more. Let’s do what has not been done.’” – Jean-Luc Godard

They teach you there’s a boundary line to music. But, man, there’s no boundary line to art.” – Charlie Parker

So then, it’s time to fill up the comments boxes with lyrical or musical questions. There may be few answers, except how in the form of playlists, chosen by our excellent guest guru this week, pejepeine! Place your suggestions below until the bell goes at 11pm on Monday for playlists published next week.

Parallel topics that also may inspire ideas, for example songs with and about ambiguity, and songs with intriguing narratives, as well as a much older and short list of some sample questions songs.

Posing questions …

New to comment? It is quick and easy. You just need to login to Disqus once. All is explained in About/FAQs ...

Fancy a turn behind the pumps at The Song Bar? Care to choose a playlist from songs nominated and write something about it? Then feel free to contact The Song Bar here, or try the usual email address. Also please follow us social media: Song Bar Twitter, Song Bar Facebook. Song Bar YouTube, and Song Bar Instagram. Please subscribe, follow and share.

Song Bar is non-profit and is simply about sharing great music. We don’t do clickbait or advertisements. Please make any donation to help keep the Bar running: