… and other volumes

By The Landlord

“I used to be Snow White, but I drifted.” – Mae West

“If you want your children to be intelligent, read them fairy tales. If you want them to be more intelligent, read them more fairy tales.” – Albert Einstein

“You are the fairy tale told by your ancestors.” – Toba Beta, My Ancestor Was an Ancient Astronaut

“If there is one ‘constant’ in the structure and theme of the wonder tale, it is transformation.” – Jack Zipes, The Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales

“Miracles are made of wings you forgot were on your back.” – Fiadhnait Moser

“Every man's life is a fairy tale written by God's fingers.” – Hans Christian Andersen

“There is the great lesson of 'Beauty and the Beast,' that a thing must be loved before it is lovable.” – G.K. Chesterton

“Two forces create eternity – a fairy tale and a dream from the fairy tale …. The world is a fairy tale; we are its guardians.” – Dejan Stojanovic, The Sun Watches the Sun

“Were I asked, what is a fairytale? I should reply, Read Undine: that is a fairytale ... of all fairytales I know, I think Undine the most beautiful.” – George MacDonald, The Fantastic Imagination

“If you ever find yourself in the wrong story, leave.” – Mo Willems, Goldilocks and the Three Dinosaurs

“Fairy tales are more than true: not because they tell us that dragons exist, but because they tell us that dragons can be beaten.” – Neil Gaiman, Coraline

“Magic is a naughty beast … Snow came back, but she didn't come back right.” – Rob E. Boley, That Wicked Apple: Snow White & Even More Zombies

“I don't know these stories as well as they know me.” – Joan Gould

Once upon a time there was a song,

A song that did not know, in heart or mind,

To which town, or tribe, or group it did belong.

Was it a foundling, born of other kind?

It wandered forests, battled beasts,

Picked through streams of guitar strings,

Found magic apples, kingly feasts,

Fought orchestras of sharp violins,

It climbed a cloud, rode on dragons,

Slew a giant, slept with elves,

Wrestled dwarves on golden wagons,

Helped others how to be themselves.

Saw cruelty, lived violent tales,

Vivid, ancient, frightening,

Moral lessons of monstrous scales,

Imagination heightening,

Journeying to find a place,

Voyaged deep with slippy mermaids,

In mirror ball it found no face,

Yet treasure came in pirate trades.

On ships it stowed away awhile,

In disguise it joined some bands,

Played pop, rock, folk, near every style,

Even grew two huge jazz hands.

Met Ali Babas, Peter Pans,

Cinderellas, and Tom Thumbs,

Played surf guitar in front of fans

With Rumpelstiltskin on the drums.

Had fun with all the fairy folk,

But somehow, still, life was Grimm,

Made boat and cloak from a magic oak,

But simply could not quite fit in.

But then adrift, it found an island

Dreamed slowly through the mist,

And suddenly it found its kind –

Themed inside a Song Bar playlist.

So then, this week we enter the fantastical and possibly vast world of the fairytale (also sometimes written fairy tale). This worldwide tradition of folklore is perhaps best known as of European origin, with the Märchen collections and creations of Germany’s the brothers Grimm, Denmark’s Hans Christian Anderson, or the Australian scholar Joseph Jacobs who unearthed and published many of the English tales, but this genre stretches way back and along across India and far East Asia, the Americas, Africa and more. But what is a fairytale and how might it come up in song?

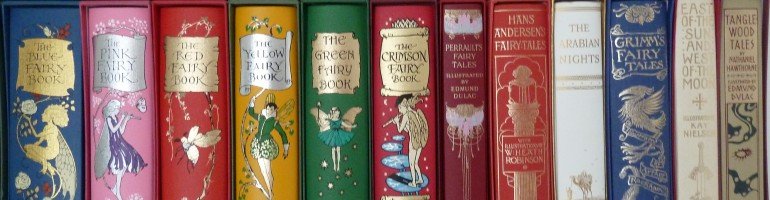

While they might combine or contain rhyme, fairytales more often short or longer prose children’s or folklore stories, and so differ from nursery rhymes, a topic which has come up here before, or indeed the more general topic of myths or mythical creatures. Nursery rhymes are also designed for for younger children, though traditionally may contain some of the same recurring underlying adult elements very prominent in fairytales – cruelty, fear, violence, ambition born from poverty or greed, but also redemption, adventure into fantasy with mythical creatures or animals anthropomorphised or combining with humans in some kind of meaningful encounter. The term fairytale derives from France – Madame D'Aulnoy's Conte de fées, first used in her collection in 1697, but many of the genre’s stories stretch back hundreds or not thousands of years, passed down initially via an oral tradition and closely tied in with song.

So to count for this week’s topic, the lyrics may refer in any way to a multitude of characters and stories in lyrics, or possibly even to the term itself. Yet in modern usage, a fairytale ending often has happy a connotation, though in traditional, established fairytales, it is clearly often not so. Love, of course, often does not end happily ever after. “Your American fairytales end that way. Real fairytales end in blood or tears,” writes author Luna Lindsey in Emerald City Dreamer.

So while the metaphorical princess might kiss the frog, who hopefully turns into her handsome prince, and all that this implies, characters also regularly get more than they bargained for, and the fairytale has variously been used to kill myth as much as create it.

A Gustave Doré illustration for Little Red Riding Hood

And there’s a vast debate about what constitutes a fairytale and how that fits into the bigger form of the a folk tale, and even a system of types of stories, or at least an attempt to define this, via the Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index (ATU Index), a a catalogue of folktale types used in folklore studies or originally composed in German by Finnish folklorist Antti Aarne in 1910. Types include repeated life lessons or story patterns, one, for example, how appearance can be deceptive, such as in Beauty and the Beast, from the original French tale La Belle et la Bête by novelist Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve and published in 1740.

And there’s an entire category of, yes, the Grateful Dead, a common theme often including that of a traveller who encounters a corpse or undead person who has not settled, and so helps to pay that person's debt and is later rewarded, such as in turn having their own life saved by a the soul of the dead person inside someone else or even an animal. Spooky.

The best known fairytale and characters may come up in many songs, but it would also be great to discover some lesser known ones. The Grimm tales, famously illustrated by Arthur Rackham, will undoubtedly figure, such as the original Sneewittchen, or Snow White, the Golden Goose, or Rumpelstiltskin, but how about the Town Musicians of Bremen (Die Bremer Stadtmusikanten), which tells the story of four ageing domestic animals, who after a lifetime of hard work are neglected and mistreated by their owners, escape and become town musicians in the city of Bremen. Though they never actually arrive in Bremen (but are celebrated in a statue there), they succeed in tricking and scaring off a band of robbers, capturing their spoils, and moving into their house. Impoverished musicians, eh? In the Aarne–Thompson index, this is known as type 130 ("Outcast animals find a new home”).

A bronze statue by Gerhard Marcks, erected in 1953, depicting the fairytale Bremen Town Musicians

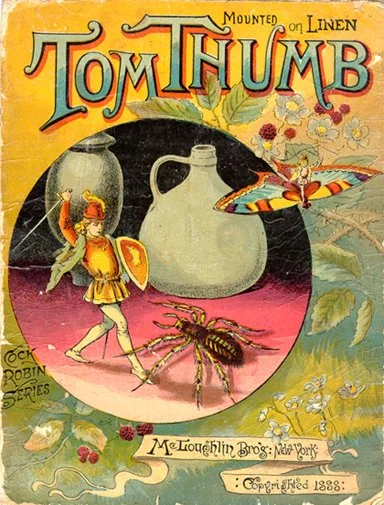

Then of course there’s England’s first printed fairytale – Tom Thumb. It was published in 1621. Tom is no bigger than his father's thumb, and is like the incredible shrinking man – his adventures include being swallowed by a cow, tangling with giants, and later becoming a favourite of King Arthur. Perhaps he was in part inspiration for the adventures of Lilliput in Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels. Tom is also referred earlier in 16th-century works such as Reginald Scot's Discovery of Witchcraft (1584), where Tom is cited as one of the supernatural folk employed by servant maids to frighten children (little devil) and his reputed home and grave is in Tattershall, Lincolnshire.

But your songs may refer to may other famous or other tales, such as many more collected and published by Joseph Jacobs, such as Jack and the Beanstalk, Three Little Pigs, or Dick Whittington and His Cat and many more. Or how about The Monkey's Paw, more of a horror short story by author W. W. Jacobs, where the paw grants three wishes but punishes those who misuse it. How many other versions of that are there? And then of course there’s Peter Pan; or, the Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up or Peter and Wendy, often known simply as Peter Pan, by J. M. Barrie, which began as a 1904 play and a 1911 novel. Or indeed arguably Lewis Carroll’s Alice Through the Looking Glass (and In Wonderland), could arguably be classed as a hugely popular, and surreal fairytale.

The variety of stories is vast and full of colour. From Africa, for example, The Nunda, Eater of People, a grim Swahili fairytale titled Sultan Majnun. The Arab world is rich source too, with Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves" (علي بابا والأربعون لصا) from One Thousand and One Nights. Sinbad the Sailor (السندباد البحري, ) is a fictional marine adventurer and the hero of a story-cycle of Middle Eastern origin. And there’s a rich selection of ales from Japan and China, such as The Magic Lotus Lantern from the Tang dynasty (618-607) or Japan’s The Cat’s Elopement, about the cats of two owners who escape and fall in love.

Northern Europe? How about Finland’s The Elf Maiden, or any number of other Nordic elven tales? Cinderella, Puss In Boots and Little Red Riding Hood meanwhile all have French origins. The Frog Princess is actually of Russian origin, among others, and is classified as “type 402, the animal bride” - of which there are quite a few.

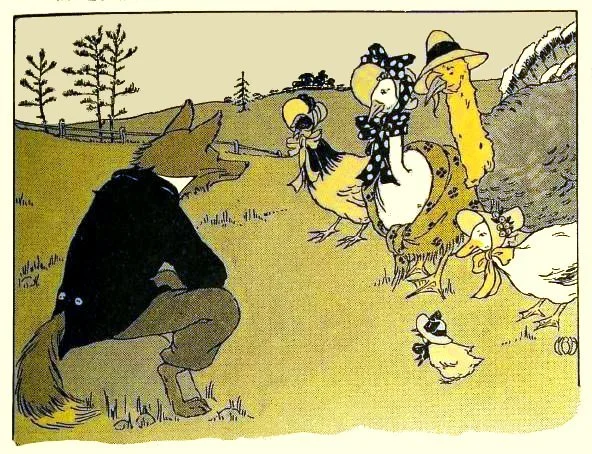

Henny Penny, meanwhile, first published in 1840, or Chicken Little or Chicken Licken in America, seems to have many sources, but all pertain to disaster, the bird in question believing that the world is about to end. ”The sky is falling” is a recurring phrase goes back nearly 3,000 years. Will it still persist in another three millennia, or is that wishful thinking?

Over egg-cited: Henny Penny, also known as Chicken Little (1916)

India is meanwhile rich in tiger fairytales, while Ireland, perhaps unsurprisingly, with a rich literary tradition, is one of the most prolific, what with leprechauns, and of course Oscar Wilde’s 1888 stories including The Happy Prince, The Nightingale and the Rose, The Selfish Giant, The Devoted Friend, and The Remarkable Rocket. Another Irish fairytale musical reference comes in the form of The Soul Cages by Thomas Keightley, but originally published in T. Crofton Croker's Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland (1825–28), about a male merrow (merman) inviting a local fisherman to his undersea home, where soul cages are his collection of human souls.

The United States is a relative beginner in creating original fairytales, but prolific in recreating them for vast commercial success, especially thought the medium of Disney. Yet there are also some key originals, such as L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful World of Oz which spawned the famous film. Also tasty is The Gingerbread Man (originally Boy) first published in 1875’s St Nicholas Magazine. But in the world of Disney, aside from the most famous and original, such as Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, there are many entertaining episodes from the Silly Symphonies series, including Three Little Pigs, The Big Bad Wolf, The Hare and the Tortoise, and here's Who Killed Cock Robin – a singer who slain by a mysterious arrow - but is the secret a sleazy Mae West figure as Jenny Wren, or a series of other vaudeville stereotypes? They all have a wondrous musicality:

This inspiring topic has attracted a huge variety of visitors from around the globe and through the expanse of time to the Bar, eager to add more perspectives.

“Snow White is an old fairy tale, so obviously the idea of vanity and obsession with youth is long-standing. With today's science, people have become crazy with trying to move their face around. It's bizarre,” says Hollywood star Julia Roberts, glancing in our mirror to check her hair, but presumably not having had any work done on her famously fine facial features.

Not all fairytales end happily, as we continually discover, if not ending in death, at least some form of profound life-shattering tragedy. But talking of which, Grace Kelly, who became a Hollywood star too, and literally married a prince, tells us: “I certainly don't think of my life as a fairy tale. I think of myself as a modern, contemporary woman who has had to deal with all kinds of problems that many women today have to deal with.”

Jack Zipes, author of The Brothers Grimm: From Enchanted Forests to the Modern World, has some key main points about the subject:

“Fairy tales since the beginning of recorded time, and perhaps earlier, have been “a means to conquer the terrors of mankind through metaphor. … Inevitably they find their way into the forest. It is there that they lose and find themselves. It is there that they gain a sense of what is to be done. The forest is always large, immense, great and mysterious. No one ever gains power over the forest, but the forest posses the power to change lives and alter destinies.”

Alexander Zick’s illustration for Snow White, originally Sneewittchen, and then Schneeweißchen

Another author on the this genre, Theodora Goss, with her book Red as Blood and White as Bone, adds that: “Fairy tales are another kind of Bible, for those who know how to read them.”

And the Bar is filled with even more famous authors of different eras who proclaim the genre to be important and powerful. “In a utilitarian age, of all other times, it is a matter of grave importance that fairy tales should be respected,” says Charles Dickens, quoting from Frauds on the Fairies, 1853.

“Folk art is, indeed, the oldest of the aristocracies of thought, and because it refuses what is passing and trivial, the merely clever and pretty, as certainly as the vulgar and insincere, and because it has gathered into itself the simplest and most unforgettable thoughts of the generations, it is the soil where all great art is rooted. Wherever it is spoken by the fireside, or sung by the roadside, or carved into the lintel, appreciation of the arts that a single mind gives unity and design to, spreads quickly when its hour is come,” adds William Butler Yeats, from The Celtic Twilight, and going deeper into the roots of the fairytale.

William Makepeace Thackeray now goes more into detail about some of the best known characters and talks about fairytales are important for his children’s education, including his daughter Ann: “There’s a great power of imagination about these little creatures, and a creative fancy and belief that is very curious to watch . . . I am sure that horrid matter-of-fact child-rearers . . . do away with the child's most beautiful privilege. I am determined that Anny shall have a very extensive and instructive store of learning in Tom Thumbs, Jack-the-Giant-Killers, etc.”

Maurice Sendak is most famous as the children’s author and illustrator of Where The Wild Things Are, but on his visit to the Bar reveals that there are very adult themes in the genre. “It’s something we've always known about fairy tales – they talk about incest, the Oedipus complex, about psychotic mothers, like those of Snow White and Hansel and Gretel, who throw their children out. They tell things about life which children know instinctively, and the pleasure and relief lie in finding these things expressed in language that children can live with. You can't eradicate these feelings – they exist and they're a great source of creative inspiration.”

And here’s Angela Carter, author of, among other great books, The Company of Wolves: “For most of human history, ‘literature', both fiction and poetry, has been narrated, not written — heard, not read. So fairy tales, folk tales, stories from the oral tradition, are all of them the most vital connection we have with the imaginations of the ordinary men and women whose labor created our world.”

And finally, here’s film directer Guillermo del Toro, creator of the powerful modern fairytale, Pan's Labyrinth: The Labyrinth of the Faun, describing the perspective of the child within the story: “Her mother said fairytales didn't have anything to do with the world, but Ofelia knew better. They had taught her everything about it.”

A clever modern take combining many fairytales in one by Deborah Allwright and Lou Carter

So then, it’s finally time to hand over the storyline to you, oh learned readers, for your songs that refer to or use fairytales in lyrics, storyline and style. And turning the great big book’s pages, I’m delighted to welcome back to the chair, Loud Atlas! Place your songs in comments below, for deadline on Monday night. Are you sitting comfortably?

New to comment? It is quick and easy. You just need to login to Disqus once. All is explained in About/FAQs ...

Fancy a turn behind the pumps at The Song Bar? Care to choose a playlist from songs nominated and write something about it? Then feel free to contact The Song Bar here, or try the usual email address. Also please follow us social media: Song Bar Twitter, Song Bar Facebook. Song Bar YouTube, and Song Bar Instagram. Please subscribe, follow and share.

Song Bar is non-profit and is simply about sharing great music. We don’t do clickbait or advertisements. Please make any donation to help keep the Bar running: