By The Landlord

“When I started learning the cello, I fell in love with the instrument because it seemed like a voice – my voice.” – Mstislav Rostropovich

“Then ceased the quivering strain, and swift returned

Into its depths the secret of each heart;” – Richard Watson Gilder

“I am a singer, first and foremost, but the medium happens to be the cello.” – Kevin Olusola

“Playing lifts you out of yourself into a delirious place.” – Jacqueline du Pré

It gets me every time. I first became aware of its sound, and a particular performance, as a young kid. I must have randomly caught a key moment on a TV programme on our black-and-white 1970s telly.

What happened? Was it the purity, the rising swell of emotion, the perfect timing and convergence of melody and orchestration, the performer's lost-in-the-moment movements, their eyes, head, neck, arms fully in throws of playing, the thrust of bow, and the passionate vibrato quiver of fingers on the cello neck? Or perhaps it was because this famously stirring piece was inspired by the tragedy of war, and the player, who was just 22 in this clip from 1967, had darkness looming in her own life. She had to stop performing just six years later, her career cut short by crippling multiple sclerosis, becoming wheelchair bound and dying at 42.

It's of course, Elgar's Cello Concerto, with the London Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Daniel Barenboim in 1967, with the incomparable Jacqueline du Pré. Here she is, and it's somewhere between the 2:20 and 2:50 mark on this video that my eyes always start to well up:

Music can do that to you. And more than most instruments, perhaps that's because, regularly pointed out, the cello is so much like a human voice transmitted through resonant wood, fingers, strings and bow. Du Pré may have been playing a 1673 Stradivarius, and other greats of the instrument might have access to perfect luthier creations of the likes of Nicolò Amati, or Nicolò Gagliano and their families, Guadagnini, Guarneri, or others of that golden17th-century era made from magically resonant wood formed in the mini ice age and perfectly crafted, but what comes out is unique to the player, from years of practice, pressure of their fingers, every sinew, and emotion expressed.

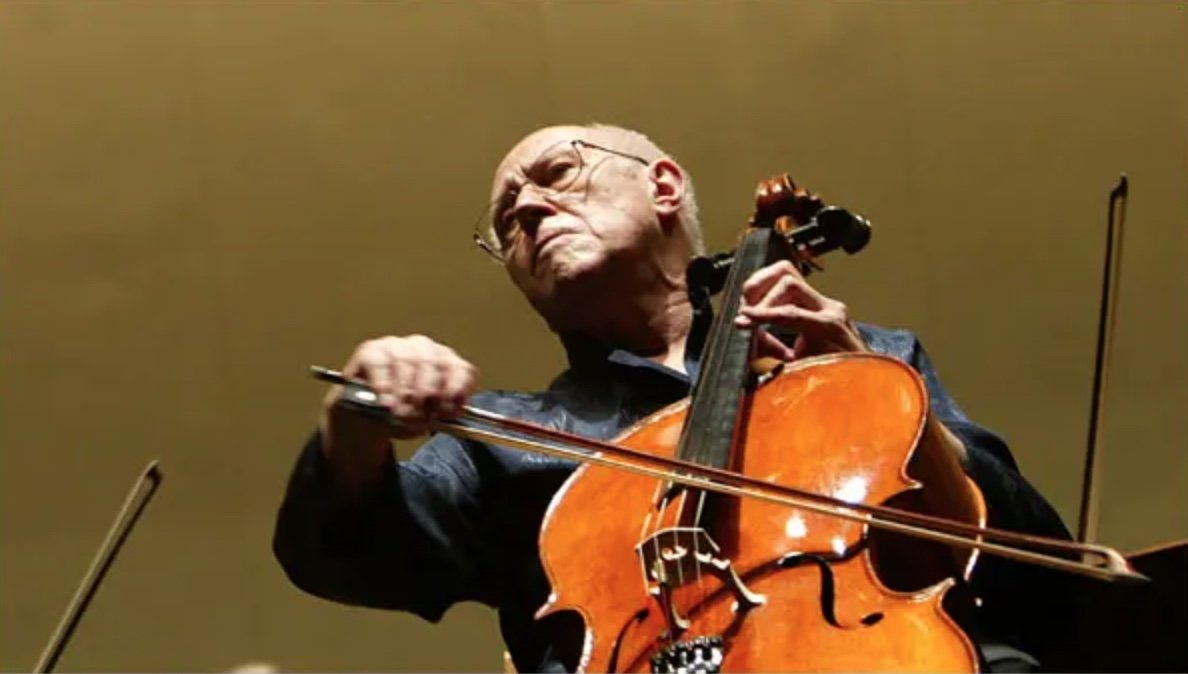

There are many great players, from Pablo Casals to Yo-Yo Ma, the hirsute Mischa Maisky, János Starker to Alisa Weilerstein and others. But Russia’s Mstislav Rostropovich (1927-2007), also a conductor and human rights activist, is widely seen as among the greatest of the greats, and also had a distinctively warm, bronzed sound and was especially lauded for his interpretations of established pieces. He declared that “the cello is a hero because of its register - its tenor voice. It is a masculine instrument, whereas the violin is feminine because of its soprano pitch. When the cello enters in the Dvorak Concerto, it is like a great orator.”

Mstislav Rostropovich

And with autumn falling, and the advent of beautiful browns, yellows, and reds all around, the time feels ripe for the dark wood of this resonant instrument be be voiced.

So then, with melodies chords, long notes or short staccato, this week we're all about the cello, not just in classical pieces but in music of all kinds where the instrument plays a strong, influential and essential part and perhaps also, if the instrument is played, where it might also feature in lyrics.

Contemporary player Slovenian-Croatian Luka Šulić says: “The cello is such a versatile instrument. It can rock like the hardest rock guitar, and it can sing like the human voice. We couldn't do what we do without the classical training. It's a hard instrument to play. There are no frets, and it takes finesse and technique.”

Talking of technique, here's an excellent explanation of the some of the subtleties of bowing technique by singer-songwriter and player Nan Kemberling:

Used widely since the 16th- and 17th-centuries, a mainstay of the classical genre, this instrument then, short also known as a violoncello, a baroque favourite and part of the the viola da braccio family, which includes, among others, the violin and viola, and shares the same perfect fifths tuning of the latter (C-G-D-A) except an octave lower, is fretless, bowed and plucked and is played sitting down, with an endpin to the floor.

But what is it about the instrument that reaches into indefinable, deep emotions? Eric Siblin, author of an intriguing music history about lost Bach manuscripts and Spanish culture, The Cello Suites: J.S. Bach, Pablo Casals, and the Search for a Baroque Masterpiece, says: “Playing the cello did feel nicely neolithic, or at least a civilized way to process the primitive.”

In more of his poem, The Cello, the 19th-century poet Richard Watson Gilder captures that strange melancholic quality in which listeners are visibly altered by the sound:

When late I heard the trembling cello play,

In every face I read sad memories

That from dark, secret chambers where they lay

Rose, and looked forth from melancholy eyes.

So every mournful thought found there a tone

To match despondence: sorrow knew its mate;

Ill fortune sighed, and mute despair made moan;

And one deep chord gave answer, “Late,— too late.”

Then ceased the quivering strain, and swift returned

Into its depths the secret of each heart;

Each face took on its mask, where lately burned

A spirit charmed to sight by music’s art;

But unto one who caught that inner flame

No face of all can ever seem the same.

All kinds of musicians, better known for other genres and instruments have possessed a cello in their youth. That includes Deep Purple's Ritchie Blackmore, who switched to the guitar, but was forced to learn classical at first. He tells us “you have to give your whole life to a cello. When I realized that, I went back to the guitar and just turned the volume up a bit louder.”

The cello is a classical instrument, but has been used extensively in pop, folk, rock and other genres from the Ink Spots to The Beatles to The Beach Boys, Pink Floyd to ELO, Nick Drake to Talk Talk to Smashing Pumpkins to Sigur Rós, Radiohead to Oasis to Arcade Fire, and there are many contemporary groups who use the instrument in punchy styles, covering heavy metal or other genres to make take it from the sensual to the sexy, such as Finland's Apocalyptica, to Pittburgh's Cello Fury or the “celloboxing” style of American Kevin Olusola. But what pieces and songs and other artists? But with you and where does the instrument features prominently and effectively? That's all down to you.

But while many bands add cello, and other orchestral strings to swell their sound when they become successful with a bigger budget, and to add a more "grown-up" or "sophisticated" sonic element, are there also bands for whom the cello has been integral from the beginning and add something new to its oeuvre?

Cross-genre musician Michael Bacon, brother of the actor Kevin, has used the instrument with an unusual Beatles connection. He explains: “I love the name Stella McCartney. It's a beautiful name the way it rolls off the tongue. A couple of years ago, I wrote a cello concerto and used that as the basis for the rhythmic and melodic structure of the main motif of the cello part.”

The cello might also feature in many film or TV score suggestions. Here's composer Ramin Djawadi: “With Game of Thrones, the most dominant instrument would definitely be the cello. That's something I just felt really captured the mood of the show very well. It has a big range. It can play really low. It can play high. And it has a dark sound."

But in popular culture,for some reason the cello is an uneasy and strange bedfellow. It sits (or stands) with shifting associations, variously portrayed as a high-brow instrument of pretentious sophistication, sometimes one of comic absurdity, to one of suppressed to open-legged, hair-tossing passion. When portrayed in film here are examples of all three, starting with the stylised and pretentious, is Tony Scott's debut 1983 movie The Hunger. an erotic vampire horror flick starring Catherine Deneuve and Susan Sarandon, and David Bowie, during that strange period of his illustrious career, here possibly miming some Schubert:

This next clip seems to both elevate and parody the instrument, as shown in Caro et Jeunet masterfully strange French release, Delicatessen (1991) in this love duet with a musical saw:

We've had the foreplay, now for the real deal and another scene again with Susan Sarandon (what was it about the cello in 1980s films?) in which the sheer explosive passion of Dvorak's concerto seems to get the better of her when she gets musically excited by a devilish Jack Nicholson in that dark 1987 comedy The Witches of Eastwick. This dubbed Czech version only seems to heighten the erotic absurdity:

So then, from sublime to the ridiculous to song and beyond, it's over to you to celebrate the range and sound of the cello. With bow in hand, and internet browser in the other, I hand over the instrument to the discerning eyes and ears of Loud Atlas who will pick from your suggestions. Deadline is 11pm on Monday UK time with playlists published next week.

Which cello number will you pick …?

New to comment? It is quick and easy. You just need to login to Disqus once. All is explained in About/FAQs ...

Fancy a turn behind the pumps at The Song Bar? Care to choose a playlist from songs nominated and write something about it? Then feel free to contact The Song Bar here, or try the usual email address. Also please follow us social media: Song Bar Twitter, Song Bar Facebook. Song Bar YouTube, and Song Bar Instagram. Please subscribe, follow and share.

Song Bar is non-profit and is simply about sharing great music. We don’t do clickbait or advertisements. Please make any donation to help keep the Bar running: