By The Landlord

“All things are poisons, for there is nothing without poisonous qualities. It is only the dose which makes a thing poison.” – Paracelsus

“Hide not thy poison with such sugar'd words;

Lay not thy hands on me; forbear, I say;

Their touch affrights me as a serpent's sting.” – Shakespeare, Henry VI, Part 2

“Let all the poison that lurks in the mud, hatch out.” – Robert Graves, I, Claudius

“Alas! they had been friends in youth; but whispering tongues can poison truth.” – Samuel Taylor Coleridge

“There are poisons that blind you, and poisons that open your eyes.” – August Strindberg, The Ghost Sonata

“Fie on these dealers in poison, say I: can they not keep to the old honest way of cutting throats, without introducing such abominable innovations from Italy?” – Thomas de Quincey, On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts

“To poison a nation, poison its stories. A demoralised nation tells demoralised stories to itself.” – Ben Okri

“Everybody's got their poison, and mine is sugar.” – Derrick Rose

Nancy Astor: “Sir, if you were my husband, I’d put poison in your tea.”

Winston Churchill: “Madame, if you were my wife, I would drink it.”

So, what’s yours? That apparent, albeit witty, caustic exchange between the first female MP and the cigar-toting Prime Minister may be apocryphal. The gag was first published in around at the end of the the 19th century in various newspapers, such as the The Listener, The Boston Transcript cited in the New York Tribune and others, then in 1900 the humorist Marshall Pinckney Wilder claimed it as his own. But that’s rumour and gossip for you. We can all mix in a little poison into words, and as Churchill put it elsewhere: “Politics are very much like war. We may even have to use poison gas at times.”

But more on that later. This week it’s time to delve deep in the deliciously destructive, dark, colourful world of poison and its toxic tales, from the gradually harmful to the downright deadly substances, natural or manufactured, that remorselessly reek internal violence. It might involve deadly animals, plants and chemicals, infamous poisoners or the famously poisoned. The more specific and detailed the better, but it could also spread through the veins and organs of society into more metaphorical venom.

Poisons stretch far back into history, myth and mystery, in literature, art and music, stories packed with murderous tales, tragic accident, or mass suicide, from Plato’s telling of how Socrates took hemlock, much to most people’s alarm, accepting the pitfalls of democracy in a death sentence, to centuries of scheming political overthrow and hidden acts of vengeance. From various overthrown Persian kings to Xu Pingjun, the first empresses of China’s Emperor Xuan, the alleged poisoning of Roman Emperor Claudius by his wife Agrippina, centuries later, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI from eating poisonous mushrooms, various slippings into drink by Lucrezia Borgia, to controlled deaths by ignominious cyanide capsule by the doomed Hitler and Eva, Göring, Himmler, and the Goebbels family.

Poison captures a range of emotions and associations, of cowardice and sacrifice, subterfuge and violence, horribly slow or fast suffering, but sometimes also an easier exit. It is both natural and yet wholly unnatural.

Russia’s history shows that country to be specialist in the field. Grigori Rasputin was slipped oodles of potassium cyanide, but that didn’t even work, so his assassins’ attempts ended up a bit less subtle. But it certainly did on many others including Nikolay Khokhlov, poisoned by radioactive thallium in Germany in 1957 for refusing to work as a KGB assassin or Alexander Litvinenko, poisoned by radioactive polonium-210 after an incident in London that could come straight from some James Bond movie.

Some however, have luckly survived poisoning attempts, such as journalist Anna Politkovskaya, Ukraine’s Viktor Yushchenko (dioxin), ex-KGB colonel Viktor Kalashnikov (mercury), and with the barely detectable Novichok, opposition leader Alexei Navalny during a flight from Tomsk to Moscow, and Sergei and Yulia Skripal, the Russian former double-agent and his daughter in, of all places, Salisbury, Wiltshire in 2018, possibly perpetrated by two visitors from abroad who, when interviewed claimed they simply visited the city just “to see the famous cathedral”. To say this is all a bit dodgy is putin’ it mildly.

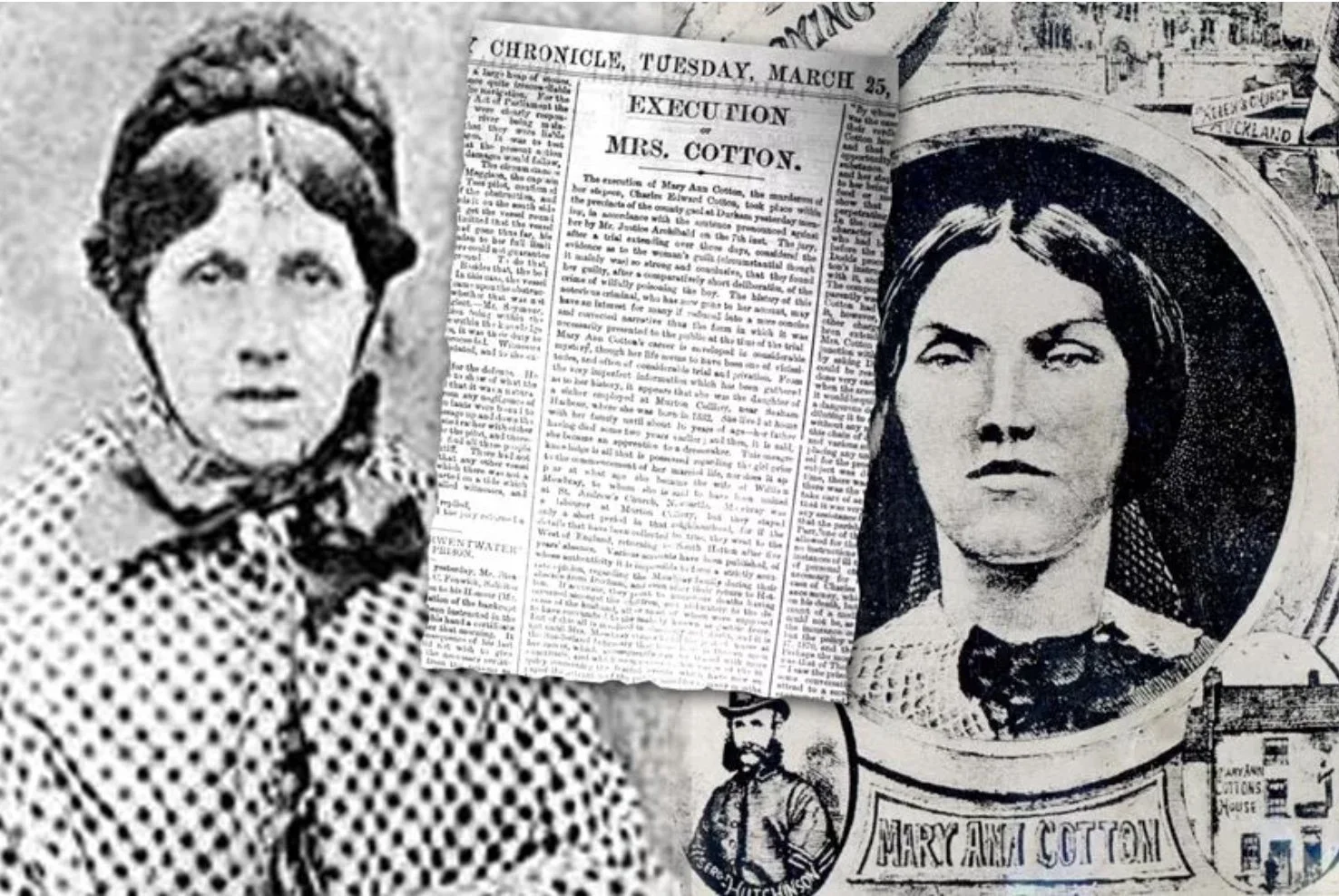

But the impressively ruthless Russian range of poisonings is nothing new. History has seen many famous poisoners quietly getting rid of enemies, rivals and family members, from Mary Ann Cotton, the so-called original black widow, who killed four husbands for the insurance money and at least eight children in the process, with arsenic her method of choice. Detective techniques were slow to catch up with her sly, subtle focus, but she was eventually sentenced to hang in 1873, when a nursery rhyme about her did the rounds …

Mary Ann Cotton, she's dead and she's rotten

Lying in bed with her eyes wide open.

Sing, sing, oh what should I sing?

Mary Ann Cotton, she's tied up with string.

Where, where? Up in the air.

Selling black puddings, a penny a pair.

Mary Ann Cotton

Poisoning’s power comes from it’s slow invisibility. In the Tori Telfer’s book, Lady Killers: Deadly Women Throughout History, the author discusses the nature of this murderous method:

“Poison is for weaklings, they say. The English poet Phineas Fletcher (1582-1650) may have been the first to coin the term “coward's weapon,” but the opinion has not dissipated in the centuries since; even a character in George R. R. Martin’s Game of Thrones recently sniped that poison was a gutless way to kill. Poison is sneaky, it’s slow, and you can poison someone without spilling a drop of their blood or awkwardly making eye contact with them midimpalement. As such, it doesn’t get a lot of cred for being scary. Poisoners simply don’t terrify people the way, say, disembowlers do.

But that’s unfair, because poisoning requires advance planning and the stomach for a drawn-out death scene. You need to look into your victim’s trusting eyes day after day as you slowly snuff out their life. You have to play the role of nurse or parent or lover while you sustain your murderous intent at a pitch that would be unbearable for many of those who’ve shot a gun or swung a sword. You’ve got to mop up your victim’s vomit and act sympathetic when they beg for water. While they scream that their insides are on fire, you must steel yourself against the dreadful sight of encroaching death and give them another sip of the fatal drink. A coward’s weapon? Not so much. Poison is the weapon of the emotionless, the sociopathic, and the truly cruel.”

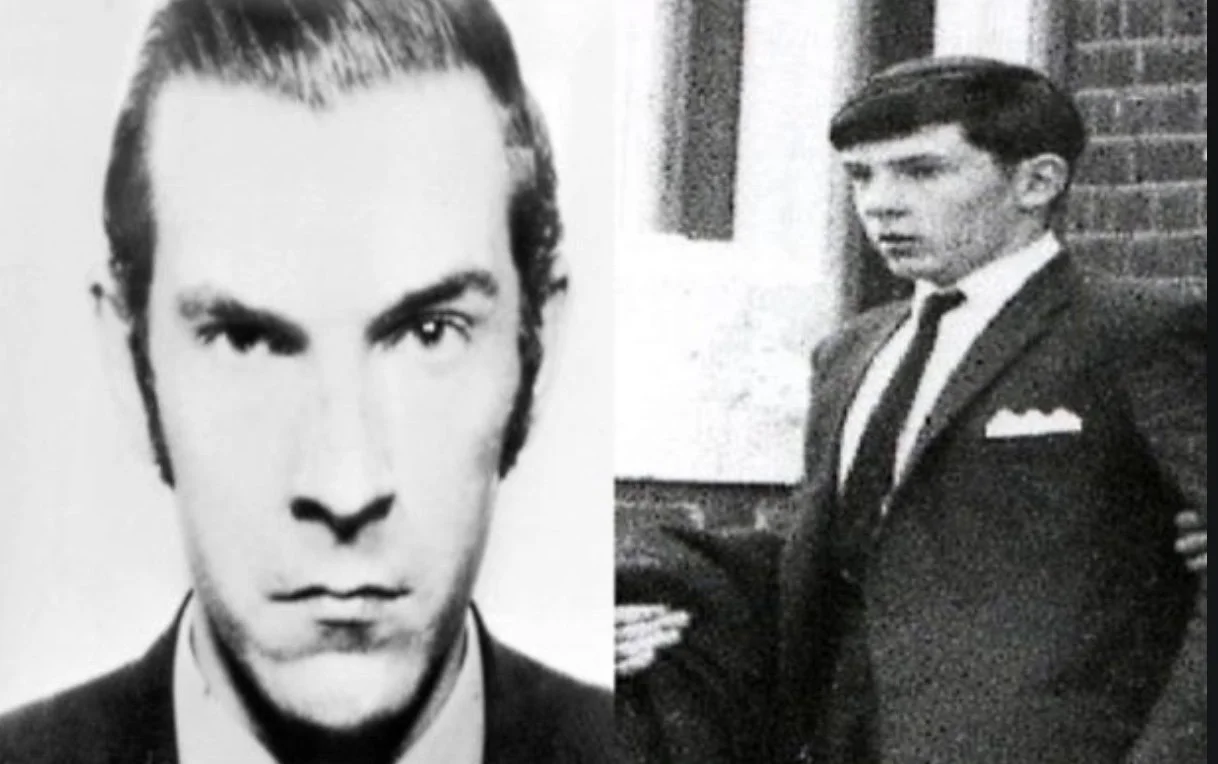

And while Cotton’s campaign was ruthless, it was not nearly as inventive as at of Graham Frederick Young (1947–1990), also known as the Teacup Poisoner and the St Albans Poisoner, a highly disturbed but certainly resourceful individual who had an obsession with the chemistry of killing. Among his declared heroes was the notorious Victorian poisoner William Palmer (1824 –1856) as well as Hitler and he also had a huge interest in black magic. He ended up in Broadmoor Hospital aged 14, but that didn’t stop him wreaking havoc to the internal organs of his victims, initially his stepmother and sister, variously using antimony acquired from a local chemist, then belladonna (also known as deadly nightshade), and in Broadmoor, he was suspected of killing a fellow inmate by using cyanide created from plentiful laurel bushes in the grounds. His story is long and complicated but certainly has a running theme. Harpic was later found in tea urn, and in a much later case, thallium acetate turned up in the drink of various victims’ tea. He was convicted of two murders and two attempted murders, but was almost certainly more unprovenly prolific. His story was dramatised in the film The Young Poisoner's Handbook (1995).

Chemical romance: poison obsessive Graham Young

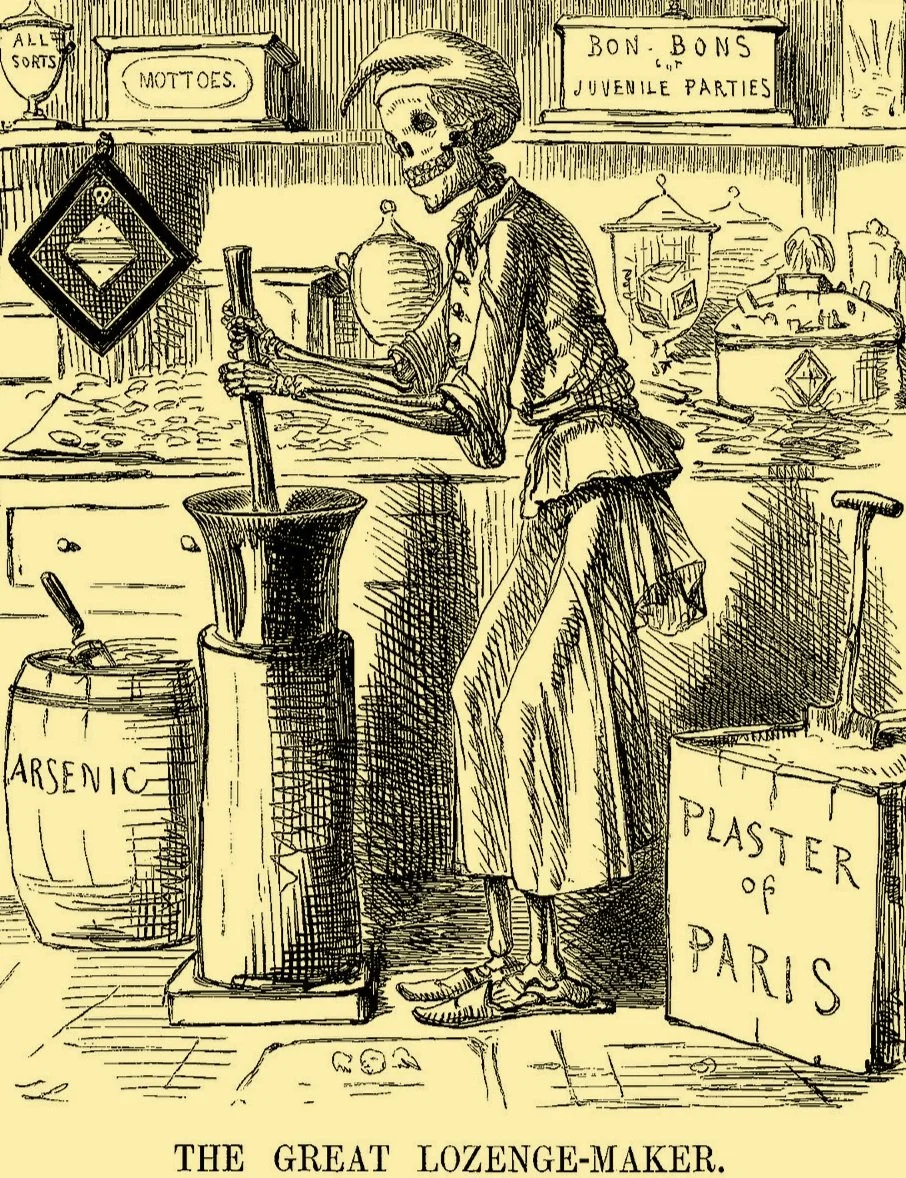

Poisonings don’t just come individually, but sometimes en masse and with greater causes of corruption or incompetance. In 1858, there was the strange case of the Bradford sweets poisonings which affected more than 200 people and killed 21, when William Hardaker, known to locals as “Humbug Billy”, sold peppermint humbugs from a stall in the Greenmarket in Bradford, West Yorkshire, where somehow arsenic got mixed up in the sugar.

The Bradford Streets Poisonning of 1858

Mass poisoning have happened in many forms, on purpose or otherwise. There’s the infamous Peoples Temple cult of 1978, in which more than 900 died by cyanide-laced punch, from the orders of Jim Jones.

But then also the other more accidental, but corrupt and preventable disasters, such as the 1971 Iraq poison grain disaster when at least 650 people died after eating methylmercury-treated grain intended for seeding. But not much can be worse than the 1984 Bhopal disaster in India, when accidental release of poisonous gas from a pesticide plant in India that killed over 10,000 people. Pesticides are a slow-motion killer, causing cancer across the world but here was evidence of it happening far more dramatically.

Poison dart frog, Ranitomeya amazonica

Perhaps your song suggestions might touch on more natural causes of death from the animals kingdom, from the snakes, spiders and more who have evolved defence and hunting mechanisms. From these there is certainly a colourful cast list, such as the saw-scaled viper, the king cobra, the banded krait, black mamba, or beaked sea snake. Perhaps who might peer carefully at the golden dart frog, Brazilian wandering spider, various stonefish, the blue-ringed octopus, the marble cone snail, or perhaps deadliest of all, the inland taipan (Oxyuranus microlepidotus) also called, appropriately, the fierce snake, which delivers a mix of scary neurotoxins, procoagulants, and myotoxins that paralyse and damage muscles, inhibit breathing, cause haemorraging in blood vessels and tissues.

Warning colours: banded krait

Top of the toxic list? The taipan may be physically evolved that way, but surely nothing is more poisonous than man. “Human brutes, like other beasts, find snares and poison in the provision of life, and are allured by their appetites to their destruction,” wrote Jonathan Swift in that fiercest of biting social satires, Gulliver’s Travels.

And here’s Pliny The Elder: “We rest not contented with natural poisons, but betake ourselves to many mixtures and compositions artificial, made even with our own hands. But what say you to this? Are not men themselves mere poisons by nature? For these slanderers and backbiters in the world, what do they else but launch poison out of their black tongues, like hideous serpents?”

We could go deep into the environmental leaking into lakes and rivers and seas, but let’s hear from various Bar visitors on all sorts of even wider form of poisoning, from the mind to the wider world.

“Resentment is like drinking poison and waiting for the other person to die,” declares Saint Augustine.

“Unforgiveness is like drinking poison yourself and waiting for the other person to die,” adds Marianne Williamson.

“Christianity gave Eros poison to drink; he did not die of it, certainly, but degenerated to Vice,” adds Friedrich Nietzsche, holding his copy of Beyond Good and Evil.

An ongoing theme is that the malevolent machinations of politics is a particularly poisoned chalice for both users and used.

“In every tyrant's heart there springs in the end this poison, that he cannot trust a friend,” says Aeschylus.

“Power is poison. Its effect on presidents had always been tragic,” adds Henry Adams.

But not just presidents and not just metaphorically. Here’s Noam Chomsky: “In 1961, the United States began chemical warfare in Vietnam, South Vietnam, chemical warfare to destroy crops and livestock. That went on for seven years. The level of poison - they used the most extreme carcinogen known: dioxin. And this went on for years.”

“The American fascist would prefer not to use violence. His method is to poison the channels of public information,” declares Henry A. Wallace, a remark ever more prescient when you look at many of the right-wing media outlets at large today.

“The idea of some people being less than people is poison to any society and needs to be named as such in order to halt its spread before it turns the soul of a society septic,” writes Richard Flanagan.

Some might argue that modern mass consumerism, or indeed food consumption is a slow form of poison in itself. Here’s M.J. Carter, in the food manufacturing industry book, The Devil's Feast:

“For decades, chalk and alum have been added to bread, and burnt corn and peas ground up to make coffee. Vinegar is rendered sharper by the addition of sulphuric acid, arrowroot is added to milk to thicken it, mustard is eked out with flour, strychnine is added to beer for bitterness and green vitriol to encourage a foaming head. And these are but the harmless manipulations…. Strychnine and vitriol in beer? … And in gin too. Enough to impart hallucinations and a nasty disruption of the bowels. And I have seen far worse: indianberry – very toxic – added to beer to make it more intoxicating. Custard flavoured with laurel – a mortal poison; pepper made from floor sweepings, comfits from china clay. Double Gloucester cheese coloured with red lead. Lead, copper, mercury, arsenic – deadly, all – they are everywhere. I myself can attest that lead salts taste quite delicious … would you rather be hungry or dead?”

Here’s looking at yew …

But let’s now finish off this poison menu with some entertaining examples from film and fiction. Poison plots are as ripe as any, running from Shakespeare the modern day. Hamlet’s entire fate is triggered by the poisoning of his father. Romeo takes poison when he thinks Juliet as died ahead of him, but it is also the entire family feud that has triggered this toxicity:

“There is thy gold, worse poison to men's souls,

Doing more murder in this loathsome world,

Than these poor compounds that thou mayst not sell.”

“Poetry… it consumed Sappho’s young years, it nourished Goethe’s old age. Drug, the Greeks called it, both poison and medicine,” writes Umberto Eco in Foucault's Pendulum. But what lyrical poison comes up in sung.

Any sightings of Poison Ivy? Will anyone take a bit of the poison apple in Snow White, or murders in Agatha Christie, Gustave Flaubert, Alexandre Dumas or Arthur Conan Doyle and his Sherlock Holmes cases?

Some poisonings, are, dare I say, quite dramatically exciting. In the Game of Thrones series of books, George RR Martin incidentally, also writes about an antidote: “Laughter is poison to fear.”

But there are no antidotes to the shock and blood-curdlingly satisfying revenge enacted when the psychopathic King Joffrey takes a greedy glug of dodgy wine in this superb series climax clincher (spoiler alert if you still haven’t seen it). Note the laced irony of various buildup lines and the sheer gut-twisting surprise of it all.

Joffrey gets a little bit choked up in Game of Thrones

But on a more darkly comedic note, there are few more entertaining poison-themed films that 1944’s Arsenic and Old Lace, an early Cary Grant classic in which he plays Mortimer, returning to live with Abby and Martha, the elderly aunts who raised him in the old family home. Searching for the notes for his next book, Mortimer finds a corpse hidden in the window seat. But to his shock, Abby and Martha cheerfully explain that they are responsible, that as serial murderers (although they don’t call it so), they administer to lonely old bachelors by ending their "suffering". They post a Room for Rent sign to attract victims, then serve a glass of elderberry wine spiked with arsenic, strychnine, and cyanide while getting acquainted with friendly parlour conversation. How very civilised, but what will Mortimer do about it?

So then, what poisonous examples in music might lure in your listening pleasure? Might they be literally be about toxins or take a wider meaning? Colourful and specific is best, but poison of some kind must be key.

Carefully examining all the evidence is this week’s chief chemist of sharp senses and musical taste – DiscoMonster! Deadly nightshade deadline is 11pm UK time on Monday. Place your poisonous examples in the comments tray below for playlists published next week. So, what’s yours?

New to comment? It is quick and easy. You just need to login to Disqus once. All is explained in About/FAQs ...

Fancy a turn behind the pumps at The Song Bar? Care to choose a playlist from songs nominated and write something about it? Then feel free to contact The Song Bar here, or try the usual email address. Also please follow us social media: Song Bar Twitter, Song Bar Facebook. Song Bar YouTube, and Song Bar Instagram. Please subscribe, follow and share.

Song Bar is non-profit and is simply about sharing great music. We don’t do clickbait or advertisements. Please make any donation to help keep the Bar running: