By The Landlord

“Coolness is the proper way you represent yourself to a human being.” – Robert Farris Thompson

“If you can keep your head when all about you

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you …” – Rudyard Kipling

“Let your soul stand cool and composed before a million universes.” – Walt Whitman

“I just can't believe that anyone would start a band just to make the scene and be cool and have chicks. I just can't believe it. I’d rather be dead than cool.” –Kurt Cobain

“For you know that it's a fool who plays it cool, by making his world a little colder.” – Paul McCartney

“Everyone knows that in most people's estimation, to do anything coolly is to do it genteelly.” – Herman Melville

“They call me Mr Tibbs!” (from The Heat of the Night)

“I am the me I choose to be … Acting isn't a game of "pretend." It's an exercise in being real.” - Sidney Poitier

Chill, phat, dope, sic. Yeet, fleek, sweet, lit. What's cool, mack daddio, what defines it?

Is it fad-ish and fleeting, or timelessly calm, and slow heart-beating? It’s easier to say what it is not, but within our language, cool is also, at times – hot.

In fashion and style, cool struts a thin line between brightly coloured bird, and on the other, the utterly absurd. Splendour of peacock, or dandy affectation of the pink-wigged Baroque? Certainly not poodle rock.

Cool is confident. Or is in nonchalant? Outrageously ooh-la-la? Or snobbishly sang-froid?

Zoot suits and spats, a jazz man who skilfully scats? Or just a flock of twats in wide-brimmed hats?

What’s in the house? A daring new dance, from a rhythm of Richard Strauss? Who’s taking the pulse? Is it time for the waltz?

A nation of gentlemen affect Byronic limp and cane? Trending buzzwords to click the inane?

Coolness is creative, exciting, inspiring. Yet attempts to become it are often misfiring.

This week then, we’re not measuring temperature, although it’s related, but the aesthetic, social, cultural and elusive state of coolness, and how it is captured lyrically or musically in song. What could possibly go right? Or wrong?

Coolness is tricky, a bit like chasing shadows. In a New Yorker article in 2013, titled "The Coolhunt”, cool is given three characteristics:

“The act of discovering what's cool is what causes cool to move on.”

“Cool cannot be manufactured, only observed.”

“[Cool] can only be observed by those who are themselves cool.”

Coolness though, most likely originally emanates, ironically, out of a very hot continent. And like most things human, that’s Africa, and its spreading diaspora.

Itutu is, as described by Robert Farris Thompson, professor of art history at Yale University, is translated as “mystic coolness”, one of the pillars of a religious philosophy created in the 15th century in West Africa, now Nigeria, particularly of cultures of the Yoruba people and might emanate from the love deity Òsun. It’s also naturally related to water, but that’s as much a metaphor.

In his book, Flash of the Spirit: African & Afro-American Art and Philosophy, Thompson describes itutu as covering various qualities. Physical beauty and style, but also the powers of conciliation and gentleness of character, generosity, grace, and the ability to defuse fights and disputes. Similarly Thompson cites the Gola people of Liberia, who define itutu as the ability to be mentally calm or detached, in an otherworldly or detached fashion from one's own difficult circumstances, to be nonchalant in situations where hot-headed emotion might otherwise take over.

So itutu covers key areas of an outer and inner existence. Of the former:

“The Yoruba assess everything aesthetically – from the taste of a yam to the qualities of a dye, to the dress and deportment of a woman or a man.”

And of the inner self:

“When a person comes under the influence of a spirit, his ordinary eyes swell to accommodate the inner eyes, the eyes of the god. He will then look very broadly across the whole of all the devotees…”

Original cool: bronze Yoruba sculpture from the 12th century

In the cool-and-calm-as-a-cucumber behavioural aspect of itutu, in a further essay, academic Scott Ainslie goes further on aspects known as Ashe and Iwa:

“When a person has successfully cultivated a greater vision of the world (Ashe), and if they have the inner will and strength of good character (Iwa) to bring that vision into being, their actions, their visage, their comportment and behaviour will begin to express an immutable nobility. They will carry themselves with dignity and modesty. They will be honest and neither unnecessarily or excessively humble or proud. Holding to their greater, inspired vision, they will be untroubled by irritations, large or small. These are remarkable external qualities that can be observed by the community at large. They are described as Itutu.”

As this philosophy an spread across the world, particularly when Africans were stolen into slavery, itutu, was, as we can imagine, something required in face of extreme adversity.

But of course the definition has evolved in many ways, from Haiti to the southern US states and beyond into communities and cultures in the bigger cities. Coolness seems originally a cultural perception as emanating from the oppressed and impoverished, as well as among gangsters and criminals, and ‘prison chic’, an attitude fostered by rebels and underdogs. Slaves and prisoners to bikers, open-rebellion dissidents to defiant, ironic, trend-seeking teenagers in the evolution of jazz, pop, rock and hip hop.

Coolness of course expresses itself in other cultures too, from deportment and style of Japanese samurai, or the Edo period with traditional aesthetic ideals of iki and sui.

It’s a concept that’s long been brewing in Europe, but less among the poor, more related to the affectations of the “aristocratic cool”, known as sprezzatura, depicted in the ambiguous detachment on the face of Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa, and particularly on Raphael's Portrait of Baldassare Castiglione, also in the Louvre, the portrait of a high-ranking Renaissance gentleman who has an attitude, and as we see, is almost shrugging with his eyes. Sprezzatura is about grandeur, self-confidence, and societal position, literally translating as disdain and detachment:

Cool or ridiculous? Sprezzatura displayed in the face of Baldassare Castiglione by Raphael

The word cool also comes up several times in Shakespeare, but largely related to calmness in the face of adversity, such as when Hamlet is asked to, “upon the heat and flame of thy distemper, sprinkle cool patience”.

But a starting point for coolness in the context of songs might be largely about the culture of the 20th century and beyond, and must surely cover lyrics and sound, from jazz and poetry and dance and fashion in Paris and Harlem, from the jazz greats of the 1950s, particularly Lester Young’s style, described as “a free-floating, wheeling and diving like a gull”, to the brilliant evolving sparseness of Miles Davis.

Lester Young

Calmness and style again intertwine. In that time, phrases like “keep your cool” and "chill", cover dual meanings. Ted Gioia writes in A History of Cool Jazz In 100 Tracks of a literal link:

“When the air in the smoke-filled nightclubs of that era became unbreathable, windows and doors were opened to allow some 'cool air' in from the outside to help clear away the suffocating air. By analogy, the slow and smooth jazz style that was typical for that late-night scene came to be called ‘cool’.”

So this tradition continued and continues, including the Blue Note revival and “Rebirth of the Cool” with rich jazz sampling that inspired so much hip-hop in the 1990s, with artists such as Digable Planets and their stage names Butterfly, Ladybug and Doodlebug. Flowing freely, like water, or moving freely like a creature, and being very comfortable in your own identity is surely a vital aspect of cool’s definition.

Digable Planets: Butterfly, Ladybug and Doodlebug

So what coolness might you find? To close, here are some further inspiration examples that seem to combine the many sides of its definition - from keeping calm to looking timelessly stylish:

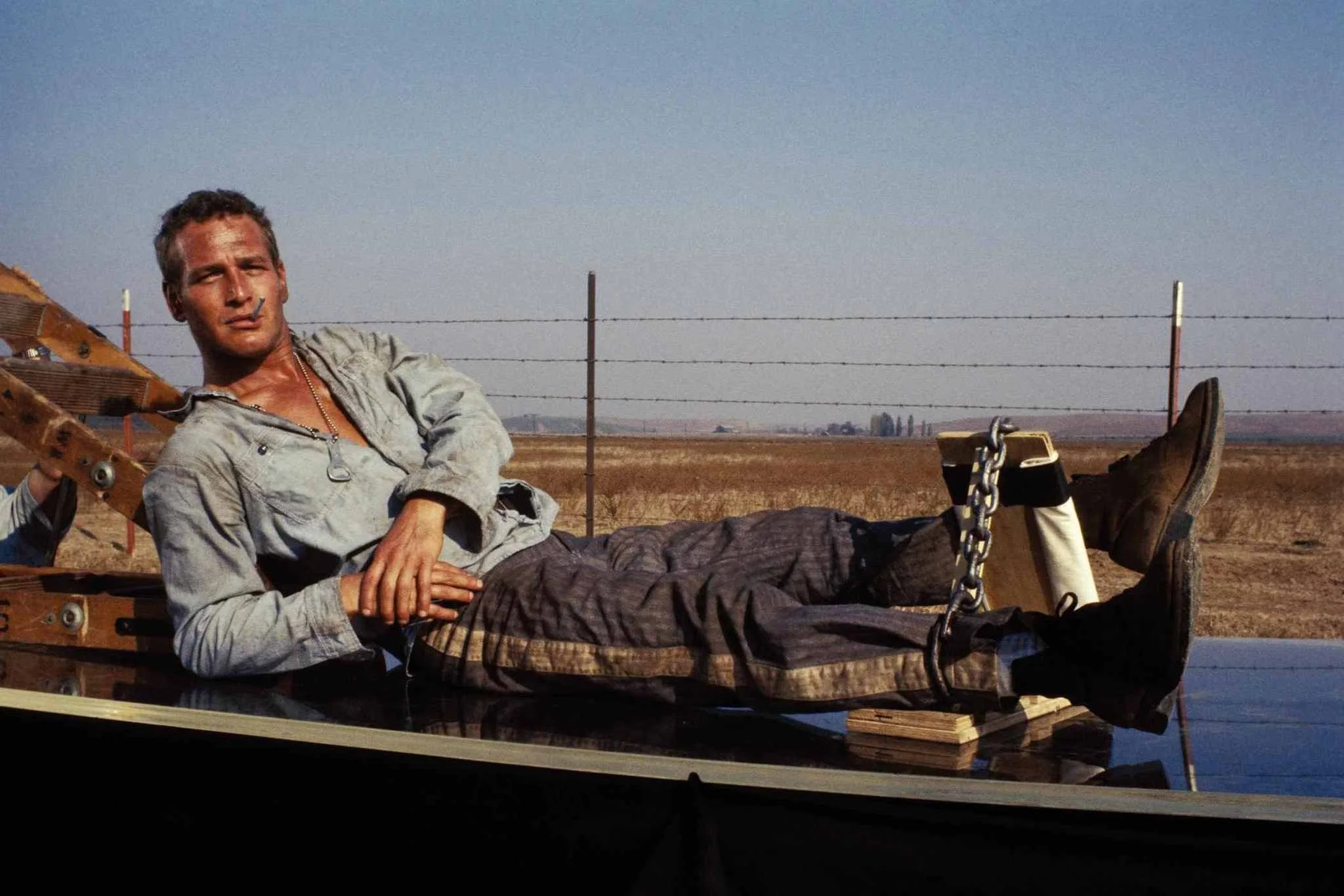

Rebellious prison chic: Cool Hand Luke

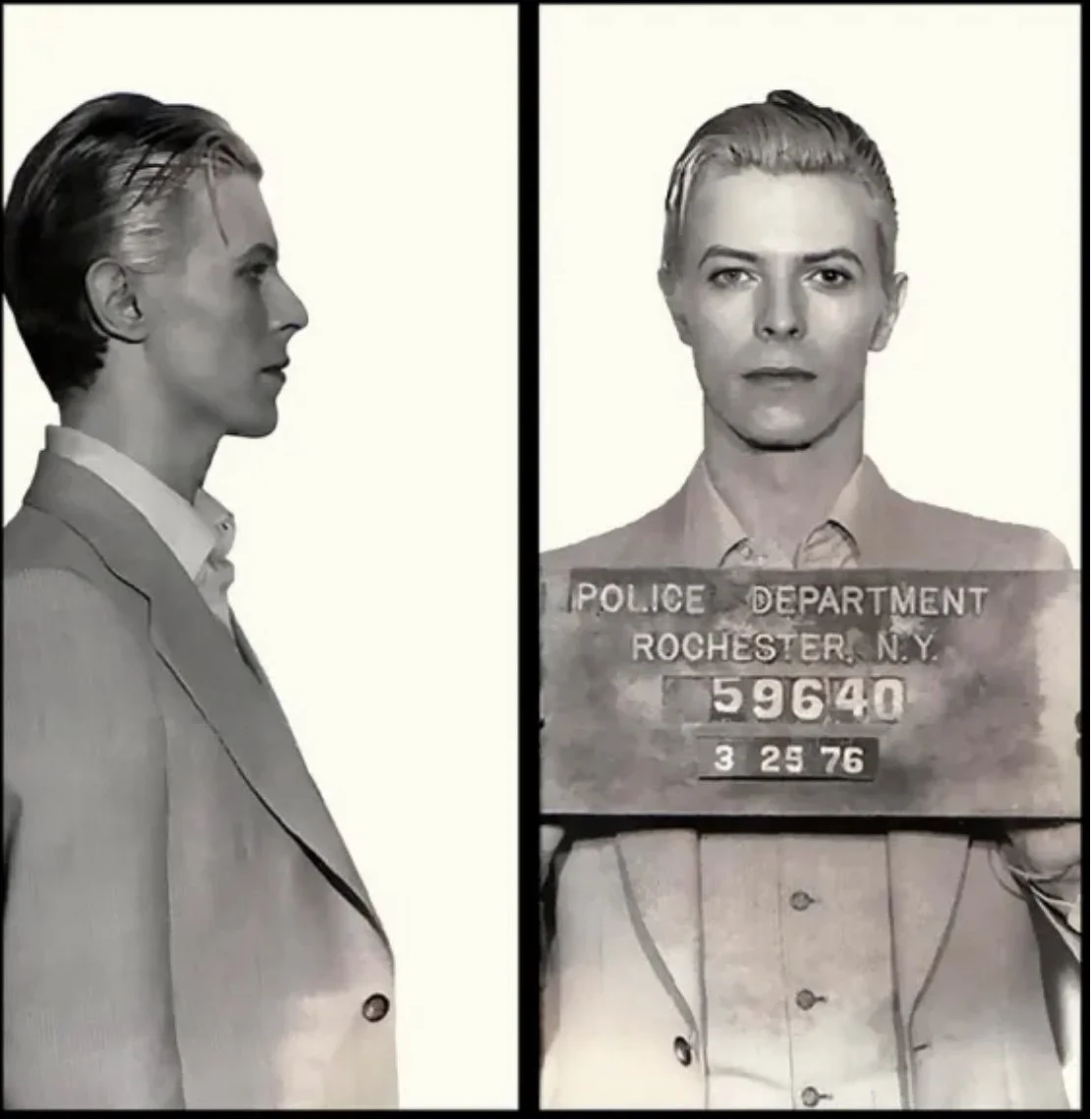

Flawless mugshot: David Bowie after a drugs-related arrest in 1976

Quentin Tarantino has traded off the idea of cool in many of his films. “Violence in real life is terrible; violence in movies can be cool. It's just another colour to work with.” Yet one of his key influences in that regard is surely the cool-headed Clint Eastwood at the climax of 1971’s Dirty Harry.

But above even Clint, arguably no one in the history of film has ever been a cooler cat than Sidney Poitier. Here he is in 1967’s The Heat of the Night, set in the heart of the deep south as a black police officer by chance having to investigate a murder. He faces off many times with Rod Steiger’s sheriff and his local racist police force, and then, in scenes that move from the cotton fields to the heat and moisture of a greenhouse, he encounters a certain Mr Endicott, leading to a moment that made a nation gasp. Check out also the ambiguous final look from the servant whose life must also be about keeping his cool:

Please then find your own definitions of cool in comments below. Keeping a cool head with no doubt many choices to make is the returning excellent regular, Loud Atlas. Deadline for nominations is Monday at 11pm (UK time) for playlists published next week. Now compose yourselves …

New to comment? It is quick and easy. You just need to login to Disqus once. All is explained in About/FAQs ...

Fancy a turn behind the pumps at The Song Bar? Care to choose a playlist from songs nominated and write something about it? Then feel free to contact The Song Bar here, or try the usual email address. Also please follow us social media: Song Bar Twitter, Song Bar Facebook. Song Bar YouTube, and Song Bar Instagram. Please subscribe, follow and share.

Song Bar is non-profit and is simply about sharing great music. We don’t do clickbait or advertisements. Please make any donation to help keep the Bar running: