By The Landlord

“He who binds to himself a joy

Does the winged life destroy;

But he who kisses the joy as it flies

Lives in eternity's sun rise.” – William Blake, Eternity

"Eternity's a terrible thought. I mean, where's it all going to end?" – Tom Stoppard

“Dearly beloved.

We are gathered here today

To get through this thing called life.

Electric word – life.

It means forever and that's a mighty long time." – Prince

"Great art is an instant arrested in eternity." – James Huneker

“In eternity there is no time, only an instant long enough for a joke.” – Hermann Hesse, Steppenwolf

Round and round it goes. Perhaps eternity serves a contradictory paradox that, if anything, at least is endlessly creative. But also destructive. Nothing lasts forever, we all know that, but the idea of eternity just seems to stick around, like BBC Radio 4’s The Archers, Willy Wonka’s Everlasting Gobstoppers, or that tin of plum tomatoes in the back of your cupboard.

The idea perhaps first gripped humanity when we began to see the sun rise every morning, and, gradually becoming eternally grateful for that repetition, we began to worship it, which sort of makes sense in a brutal young world. Perhaps more so than the idea of heaven and hell, the afterlife and every action the name of whatever god figure or religious concepts followed, most often as hiding what was more often form of social control.

But while all of our lives are a mere fart in the wind, it’s an irresistible idea that something of us might remain, whether that’s in our genes passed on to children and beyond, or something we’ve made that marks out our existence, or as the super-rich might concentrate their efforts in some form of cryogenics for some future re-awakening, just as the pharaohs would have their wealth buried with them in the tomb. But, from everlasting love, to endlessness, the forevermore, permanence, perpetuity, to infinity and beyond, perhaps something is preserved forever, however long that may be, in the form and idea and lyrics of song.

Making a permanent mark is idea that perhaps gripped Australian Arthur Stace more than most. From 1932-1967, walking around the city at night, he wrote the word ‘Eternity’ in various locations around the streets in of Sydney an estimated half a million times with flowery copperplate style. Where had that idea come from? His background was difficult, marred by an experience of ongoing impermanence. His parents were alcoholics, and his sisters ran a brothel, and he became a petty criminal, a ward of the state, an alcoholic, later a solider, but then devout Christian after hearing a Baptist preacher’s sermon about where eternity might be spent. So he spent the rest of his days, or indeed nights, writing it down everywhere, many times narrowly escaping arrest for defacing public property.

Arthur Stace, graffiti addict and eternity obsessive

But ironically, many years after his death, Mr Eternity’s mark was replicated on the Sydney Harbour Bridge during the 2000 Olympics.

Stace lives on on the Sydney Harbour Bridge in 2000

The idea, and obsession with eternity has been around a lot longer than that, and in many forms. The endless knot or eternal knot is one such longstranding symbol, in Sanskrit: śrīvatsa; in Chinese: 盘长结 or 盤長) is a important symbol in Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism. In the later various interpretations include the endless cycle of suffering of birth, death and rebirth, and the inter-twining of wisdom and compassion.

One of many forms of the Endless or Eternal Knot

Meanwhile, classical philosophy defines eternity as what exists outside time. “Eternity is said not to be an extension of time but an absence of time,” wrote Graham Greene in his novel The End of the Affair. So such a definition might include supernatural beings, gods and forces, while sempiternity corresponds to the infinitely temporal, non-metaphoric definitions, as recited in requiem prayers for the dead. Thomas Hobbes, that key figure in the 17th-century Age of Enlightenment philosophy, drew on the classical distinction to put forward metaphysical hypotheses such as "eternity is a permanent Now”. You could say that’s debate that goes on and on, like entropy.

In that same century the Italian painter Guido Cagnacci captured a number of ideas around eternity with his work depicting an allegorical woman holding up an hourglass, her elbow above a human skull as well a clutching two flowers in maturity, one of which is a dandelion clock seed head, which serve as reminders of transience. Circling around her head as a dubious halo is the ouroboros, snake swallowing its own tail, which circles back to my piece before Christmas about the repeated omnishambles of 2021. If nothing else is permanent, certainly human error might be.

Guido Cagnacci’s 1670 depiction of many ideas of eternity

Jonathan Swift’s timeless 1726 satire Gulliver’s Travels touches on many such ideas, including that of the Strulbrugg, humans in the nation of Luggnagg who are born seemingly normal, but are in fact immortal, though unlike the glamorous gods, they continue to age, and become tortuously infirm, blind and incontinent. What a may to, er, not go.

And her, in a allegorical map "The 3 Roads to Eternity" inspired by the Bible’s Matthew 7:13-14 is a the work of woodcutter Georgin François, made in 1825. It’s oddly medieval, depicting the variously infinite cycles of paths that lead to heaven or hell.

The infinite treadmill to heaven and hell in "The 3 Roads to Eternity" by Georgin François

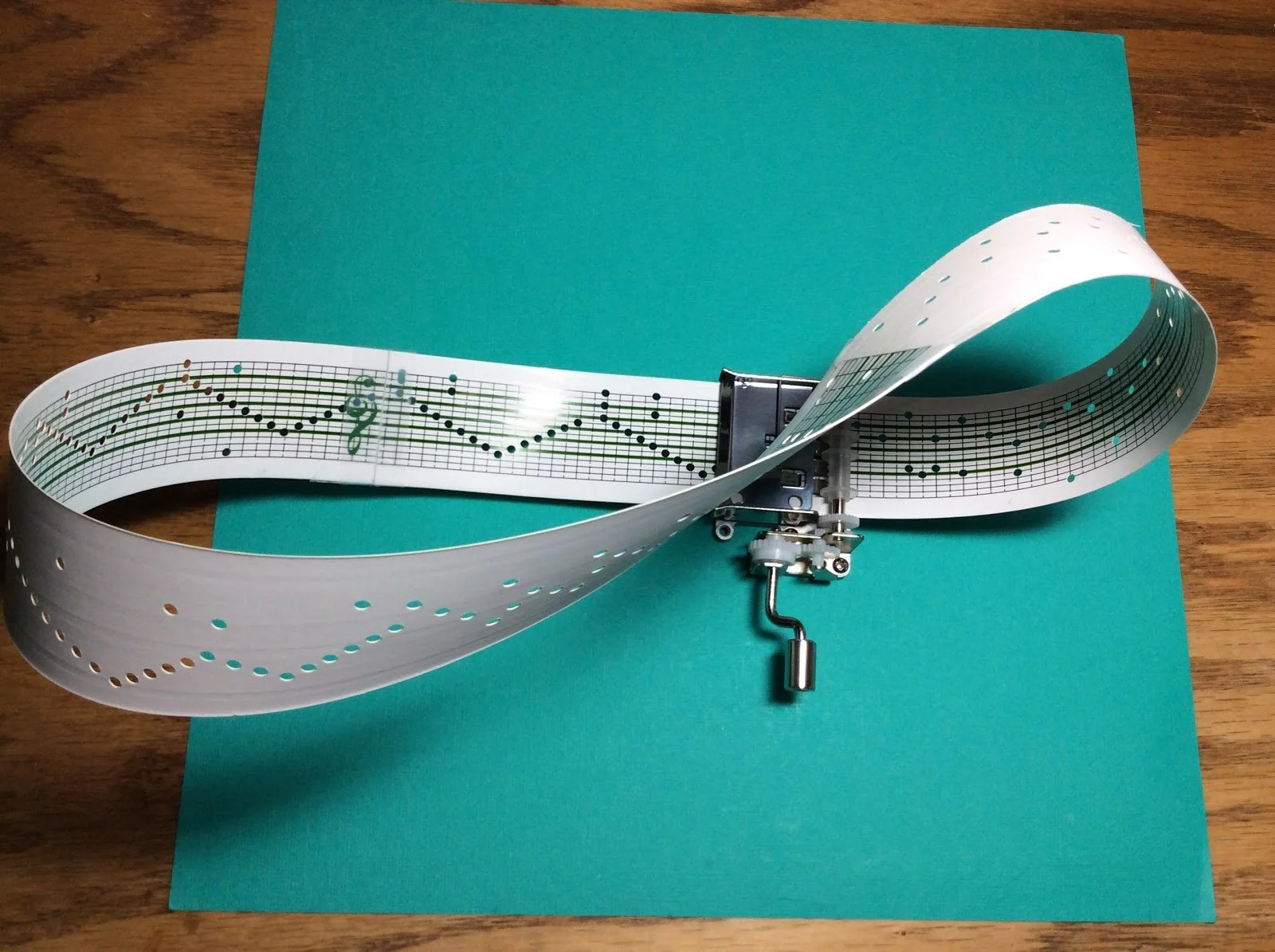

In various contexts, that non-stop cycle is something that pervades, not least in the more sophisticated form of the work of Escher, or the mathematical Möbius strip, a surface with only one side and only one boundary curve, attributed independently to the German mathematicians Johann Benedict Listing and August Ferdinand Möbius in 1858, though similar structures can be seen in Roman mosaics in the second century AD.

The world goes round, as a marble on a Möbius

All of these ideas collide very neatly in that fabulous book by Douglas Hofstadter’s 1979 book Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid, mentioned before more than once here, bringing together mathematics, art and music in a lively, witty fusion.

Explaining more about the genius of JS Bach in this respect, here’s mathematician Marcus Du Sautoy on a Numberfile video:

Is music, conceptually, at least, eternal? Another sphere of this idea comes in the form of musica universalis, also called music of the spheres or harmony of the spheres, that philosophical concept that regards proportions in the movements of celestial bodies, sun, moon, and planets – as a form of music. The theory came from Ancient Greece via Pythagorus, and was later developed by 16th-century astronomer Johannes Kepler, who did not believe this so-called music to be audible, but felt that it could nevertheless be heard by the soul. And before Kepler, Shakespeare also touched on this idea in The Merchant of Venice, in reference to

… the floor of heaven … inlaid with patines of bright gold:

There's not the smallest orb which thou behold'st

But in his motion like an angel sings,

Still quiring to the young-eyed cherubins;

Such harmony is in immortal souls;

But whilst this muddy vesture of decay

Doth grossly close it in, we cannot hear it.”

Perhaps then there’s also room for later musical interpretations of the Music of the Spheres, such as the work of early 20th-century Danish composer Rued Langgaard.

This is a topic that, of course, goes on, and inevitably there’s a near-infinite crowd coming into the Bar to say more about it. Where might these various people find common ground on the idea of eternity. First up, American 19th-century preacher Edwin Hubbell Chapin slaps his bible and stands on a table, loudly announcing, rather musically that:

“Every action of our lives touches on some chord that will vibrate in eternity.”

But not everyone agrees on the idea of a religious eternity. “Nobody could stand an eternity of Heaven,” shouts George Bernard Shaw, banging on the table, and quoting from Man and Superman.

Taking a gentler tone, musician Conor Oberst pipes up: “You can only really understand good if you have bad, so the idea of heaven or anything that happens for eternity, even if it's nice, I can't imagine it being nice forever. Even the idea of forever is kind of ridiculous.”

“Well,” says a swivel-eyed Bette Davis, “I am doomed to an eternity of compulsive work. No set goal achieved satisfies. Success only breeds a new goal. The golden apple devoured has seeds. It is endless.”

Work, love, heaven, hell. How can all this take shape? Through science? “Scientists are peeping toms at the keyhole of eternity,” says Arthur Koestler.

How else can eternity be expressed? “A photograph can be an instant of life captured for eternity that will never cease looking back at you,” suggests Brigitte Bardot, perusing some snaps of her former beauty in its prime.

Flannery O'Connor meanwhile tries to identify the difficulty of the concept of eternity. “The writer operates at a peculiar crossroads where time and place and eternity somehow meet. His problem is to find that location.”

But Gustave Flaubert, quoting from Madame Bovary, tries to grasp some of it through the prism of love: “And she felt as though she had been there, on that bench, for an eternity. For an infinity of passion can be contained in one minute, like a crowd in a small space.”

But where is that situated? Christopher Wren reckons: “Architecture aims at Eternity.” And while many of his great buildings still stand in London, will they do so forever? “Venice is eternity itself,” says Joseph Brodsky, but won’t that beautiful city sink under the sea?

But there’s some continuance to all of the contributions to this very disparate group of Bar punters. Here’s regular Friedrich Nietzsche, who interesting uses a description that reminds of the Möbius band:

“Everything goes, everything comes back; eternally rolls the wheel of being. Everything dies, everything blossoms again; eternally runs the year of being. Everything breaks, everything is joined anew; eternally the same House of Being is built. Everything parts, everything greets every other thing again; eternally the ring of being remains faithful to itself. In every Now, being begins; round every Here rolls the sphere There. The centre is everywhere. Bent is the path of eternity.”

Fellow philosopher Henry David Thoreau meanwhile likens eternity to a river:

“Time is but the stream I go a-fishing in. I drink at it; but while I drink I see the sandy bottom and detect how shallow it is. Its thin current slides away, but eternity remains.”

There seems to be a gathering momentum now that the idea of eternity is not within the individual, but in their surroundings, of nature’s cycle in constant renewal brought along by the inevitable.

“From my rotting body, flowers shall grow and I am in them, and that is eternity,” says the painter Edvard Munch.

“Death is the golden key that opens the palace of eternity,” suggests John Milton.

“The day which we fear as our last is but the birthday of eternity,“ adds Lucius Seneca.

“Forget yourself. Become one with eternity. Become part of your environment,” adds Japanese artist, Yayoi Kusama, famous for her infinite dots.

“What nature delivers to us is never stale. Because what nature creates has eternity in it,” says the writer Isaac Bashevis Singer.

William Blake, a bit of a scary, wide-eyed, and all too inspired figure for many to handle, says that the forces of nature are a bit too much for most to feel: “The roaring of lions, the howling of wolves, the raging of the stormy sea, and the destructive sword, are portions of eternity, too great for the eye of man.”

Let’s end with a vivid few lines from the poet John Clare:

“Hill tops like hot iron glitter bright in the sun,

And the rivers we're eyeing burn to gold as they run;

Burning hot is the ground, liquid gold is the air;

Whoever looks round sees eternity there.”

So then taking the musical baton, and us eternally onwards in endless cycle song, I’m delighted to welcome back to the chair, the most excellent ajostu! Place you song nominations in comments below in time for deadline on Monday at 11pm UK time (even eternity has to close eventually) for playlists published next week. To infinity, and beyond!

The same old song? Möbius music box

New to comment? It is quick and easy. You just need to login to Disqus once. All is explained in About/FAQs ...

Fancy a turn behind the pumps at The Song Bar? Care to choose a playlist from songs nominated and write something about it? Then feel free to contact The Song Bar here, or try the usual email address. Also please follow us social media: Song Bar Twitter, Song Bar Facebook. Song Bar YouTube, and Song Bar Instagram. Please subscribe, follow and share.

Song Bar is non-profit and is simply about sharing great music. We don’t do clickbait or advertisements. Please make any donation to help keep the Bar running: