By The Landlord

“A heap of broken images, where the sun beats,

And the dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief,

And the dry stone no sound of water …

I will show you fear in a handful of dust.” – T.S. Eliot, The Waste Land

“Being alone on the moors is scary; as the rain clouds settle in, it makes you realise your place in nature.” – Dave Davies (The Kinks)

“My sister Emily loved the moors … She found in the bleak solitude many and dear delights; and not the least and best-loved was – liberty.” – Charlotte Brontë

It is barren, deserted, destroyed, infertile, unkempt, neglected, toxic, eroded, unused, overgrown, sparse, bleak, of limited vegetation or biodiversity, and might be wild and green, or industrial grey or urban brownfield. But strangely, whether it’s scrub moorland or heath, barren lands or badlands, concrete covered in broken glass inhabited only by few sprouting nettles, such places make up a strange place in culture, and lay a fertile ground for if nothing else, creativity.

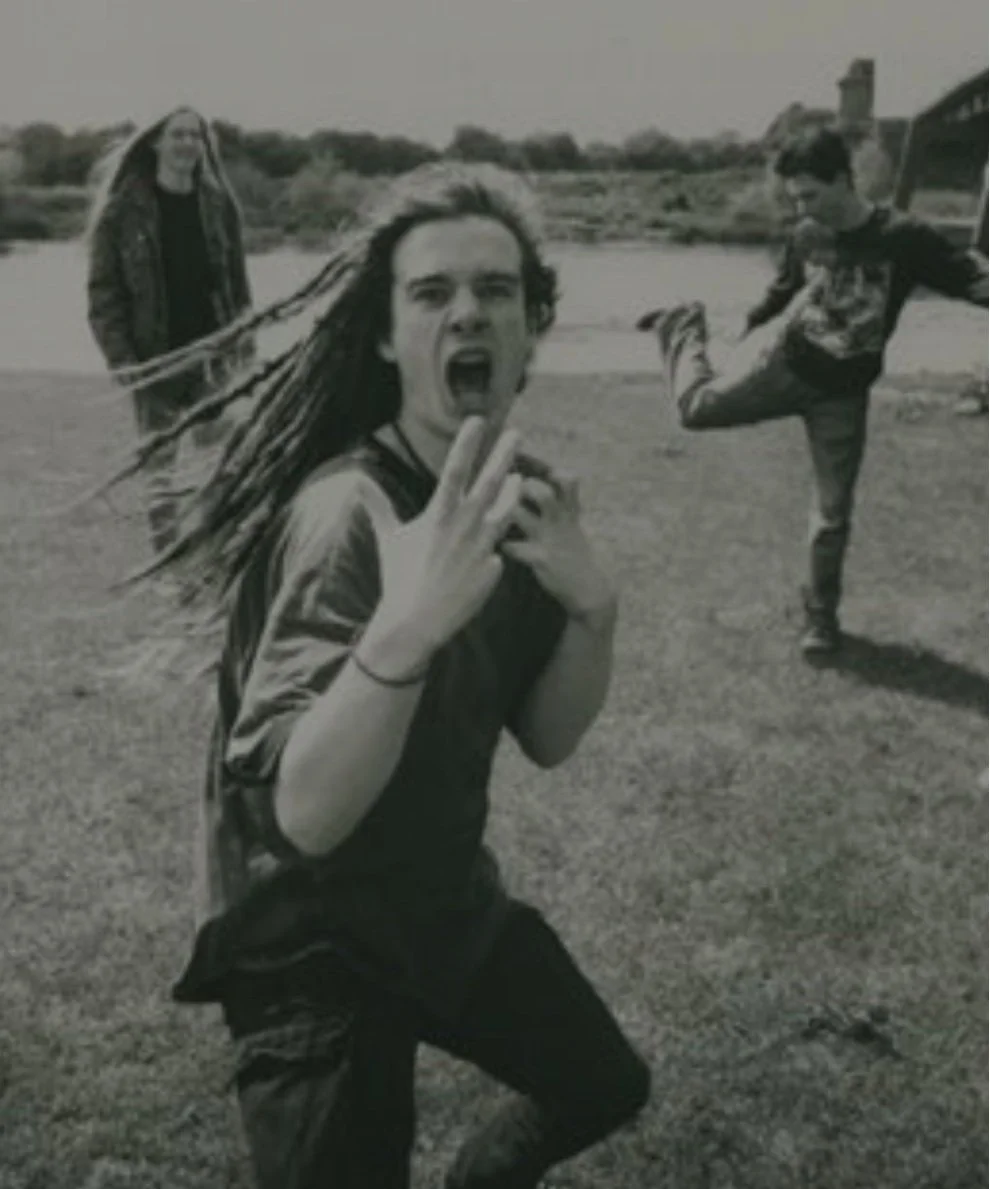

Wastelands are your classic location for bands to stand, trying to look cool for their album covers or publicity shots, and poets, especially in the 60s, 70s and 80s, to be pictured, hands in pockets, with the rain lashing down, for the covers of poetry books. Wastelands appear to be a canvas for ideas, for rebels to push against the norm and also of course, a place to get wasted. So this week it’s time to capture them when featured in song, either as the main subject, or prominently in lyrics, either in a literal or metaphorical context.

Toxic wasteland, a well of human destruction in water and ground

With seasonal scorched grass to eroded soul from flooding across the globe, and even more crucially devastation of Amazonian rainforest clearance and mining, wasteland and waste ground is a vicious cycle and a growing sight in our destructive modern world, and ongoing symptom of man-made climate change. But while the soil itself may cease to produce anything, there are other byproducts of this subject.

One person’s wasteland is another’s fertile seedbed of ideas, a breeding for the imagination in books, film, art and song. They are a setting for the unpredictable, the wild, the fearful, the strange and dystopian, and outside of lyrics, here then are a few bases for inspiration that from which others may have sprung.

Emily Bronte’s 1847 novel Wuthering Heights may follow the fates of the Lintons and Earnshaws and their adopted, wild but bullied son Heathcliff, but living within him, is the primary character of the wild, barren North Yorkshire Moors. Here is a brutal, barren beauty where only the toughest can survive, or indeed where the dead are wont to haunt.

The bleak Yorkshire moors that inspired Emily Brontë

Building on that Arthur Conan Doyle also used the backdrop of Devon’s Dartmoor for his Hound of The Baskervilles Sherlock Holmes-series novel, first serialised in 1901-02’s Strand Magazine, a dark, wild, hostile place out of which the apparently diabolical, supernatural creature emanates:

"...it was a huge creature, luminous, ghastly, and spectral. I have cross-examined these men, one of them a hard-headed countryman, one a farrier, and one a moorland farmer, who all tell the same story of this dreadful apparition, exactly corresponding to the hell-hound of the legend. I assure you that there is a reign of terror in the district, and that it is a hardy man who will cross the moor at night."

This beast story is echoed in John Landis’s fabulous 1981 movie American Werewolf in London, where the haplessly careless American tourists, after visiting the hostile Slaughtered Lamb pub, decide to ignore a local’s advice to “Keep away from the moors...stay on the road.”

"Keep away from the moors”: American Werewolf in London

Some might associate moorland with death, not least the Saddleworth Moors murders also captured in song, but that’s not the association for everyone. But just as Charlotte Brontë highlights her sister Emily’s love of the Yorkshire moors, not everyone finds them a place to fear. Scottish vet James Herriot, author of the popular All Creatures Great And Small series, described this area as the source of “ the peace which I always found in the silence and emptiness of the moors filled me utterly”.

Wasteland works in different, extreme ways. This year also happens to be the 100th anniversary of T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, that strangely evocative, and currently topical, epic poem, inspired by aftermath of the destruction of the First World War, a signpost of decay and change. It references everything from Ovid Metamorpheses to Dante’s Divine Comedy, Shakespeare, Buddhism, Hindu Upanishads, and a huge number of popular songs. It captures an era and melancholy mood of modernist decay and erosion, as song lyrics float up from the wilderness from many sources, including, the rather topical London Bridge is Falling Down, Harrigan by George M. Cohan (1907), The Maid of the Mill by Hamilton Aidé and Stephen Adams, My Evaline by Mae Anwerda Sloane (1901), Cubanola Glide by Vincent Bryan and Harry von Tilzer (1909), songs from Shakespeare plays and more. Out of this particular Waste Land of decay and death comes an at times delirious wellspring of music.

“I think we are in rats’ alley

Where the dead men lost their bones.”

“I sat upon the shore

Fishing, with the arid plain behind me

Shall I at least set my lands in order?

London Bridge is falling down falling down falling down.”

“These fragments I have shored against my ruins.”

It’s hard to draw an exact line between what is a wasteland and what is simply natural geography, so this week’s topic might also, arguably, include swamps, fens, bushland and deserts, though the later, as well as sand, have been covered before as a song topic. Perhaps a useful way in is to imagine that the land was once more fertile, but has since gone into decline either by natural or unnatural causes, and has undergone a process of being ‘wasted’.

Badlands in particular may be a potent backdrop for song, as they are a form dry terrain where softer sedimentary rocks and clay-rich soils have been extensively eroded, no-go areas difficult to navigate by foot, unsuitable for agriculture, uninhabitable where only the mad or bad or outcast might go. The Bible, of course, tells how Jesus spent 40 days and nights in a badlands desert-style hostile wilderness, and these are areas stories of outcasts, bandits and anyone hiding or on the run. So songs set in badlands might include anywhere from Argentina’s Valle de la Luna (Valley of the Moon), Big Muddy Badlands in Saskatchewan, notorious as a hideout for outlaws, or many such areas such as Badlands National Park in South Dakota, Henry Mountains area in Utah, Hell's Half-Acre in Natrona County, Wyoming and more, often dramatically rocky, unfertile, hostile places.

Hell's Half-Acre, Wyoming

There are many examples of badlands in American film, but perhaps none better than Terrence Malick’s 1973 directorial debut staring Martin Sheen as killer Kit Carruthers and his girlfriend Sissy Spacek as Holly Sargis, a couple on the run who hide out, living in a car, in the wilds of Montana, but where of course things end badly, in a terrifically acted and bleakly powerful film with a fabulous soundtrack:

Outlaw terrain: on the run in Montana, in Badlands (1973) with Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek

Wastelands are the backdrop for human destruction as much as naturally occurring terrain, and they are an ideal for settings of eco-meltdown, the dystopian, and post-apocalyptic. The most obvious example are the Mad Max movies, set in a violent, resource-scarce world. It began as as brilliant low-budget film, and became an at times ridiculously over-the-top franchise, though by 2015’s Mad Max: Fury Road is an astonish feat of breathless, stunt-filled dystopian film-making:

But not all wasteland-setting creations car chase blood and fury. Terrain Vague (Waste Land) is a poignant and powerful 1960 French film directed by Marcel Carné based on the novel Tomboy by Hal Ellson, set on a newly built HLM (habitation à loyer modéré - low-cost housing estate) wasteland and brownfield site that provides refuge to a rebellious gang of young people escaping life in the Paris suburbs. There, in a setting ruled by the chief tomboy, Dan, they share secrets, stolen goods and submit to strict rituals of the clan, blood rites of passage and feats of jumping blindfolded.

Urban outcasts: Terrain Vague (Marcel Carné, 1960)

But not all wastelands are places where humans inflict violence on each other or must be part of a gang. Waste Land is a 2010 British-Brazilian documentary film directed by Lucy Walker about artist Vik Muniz, who travels to the world's largest landfill, Jardim Gramacho outside Rio de Janeiro, to collaborate with a lively group of catadores of recyclable materials transforming refuse into contemporary art.

You can also watch the wonderful full documentary here:

And so we go full circle in the wasteland - from destruction and decay – to creativity. But now to close, and for your entertainment, here’s a gallery I’ve created of bands, some more obvious than others, posing in variously cliched, moody, mean, or strangely self-conscious ways in, dark, dusty or dank wasteland settings. Why do so many of them do this? Maybe the wasteland is the place for the rock’n’roll rebel. Click on the images below. You might spot a famous figure or two.

And so, it’s time to turn then to recycle your own materials – years of collecting music – into this week’s topic. Please place your wasteland-related songs in comments below. Picking through them for treasure, I’m delighted to welcome back to the guest guru’s chair, George Boyland! Deadline is 11pm on Monday for playlists published next week. Waste not, want for nought.

New to comment? It is quick and easy. You just need to login to Disqus once. All is explained in About/FAQs ...

Fancy a turn behind the pumps at The Song Bar? Care to choose a playlist from songs nominated and write something about it? Then feel free to contact The Song Bar here, or try the usual email address. Also please follow us social media: Song Bar Twitter, Song Bar Facebook. Song Bar YouTube, and Song Bar Instagram. Please subscribe, follow and share.

Song Bar is non-profit and is simply about sharing great music. We don’t do clickbait or advertisements. Please make any donation to help keep the Bar running: