By The Landlord

"If chocolate could sing, it would sound like the double bass." – Gary Karr

:Creativity is more than just being different. Anybody can plan weird; that's easy. What's hard is to be as simple as Bach. Making the simple, awesomely simple, that's creativity. Bach is how buildings got taller. It's how we got to the moon.” – Charles Mingus

“The bass, no matter what kind of music you're playing, it just enhances the sound and makes everything sound more beautiful and full. When the bass stops, the bottom kind of drops out of everything.” – Charlie Haden

A clasp of fingers on my neck,

a rasping straight across my chest,

jittered spasms, shock supine,

reverberant and quivering spine,

shuddered body, wood and ground,

pinching, slapping, sinews wound,

muscles stretch to full surround,

then ease to deep, soft, warmer sound.

That dream sometimes. Floats in my face.

Recurs that I'm a double bass.

But enough about my fevered, food-fuelled night imagination. It's time to play with this week's theme, on an instrument that sounds, in my mind, like somewhere between a rich, shiny, black coal seam, and thick, dark, chocolate ice-cream. Heavy, deep, mellow, mighty, rich, sustained, sombre and strong, it's the deepest, big daddy elephant at the back of the orchestra, but also in any jazz club, the elegant, six-foot tall figure standing at the bar.

The electric bass of course is everywhere, but the upright, or double bass has a distinctive other sound, softer somehow, more delicate, expressive, and it also has the more sustained, added element of being bowed as well as strings plucked. Classical and jazz may be initial go-to areas, but the double bass is a badass in many other genres, from blues to rock'n'roll, rockabilly, psychobilly, country, bluegrass, tango, folk, postpunk, proto-punk, hip hop and, of course, pop.

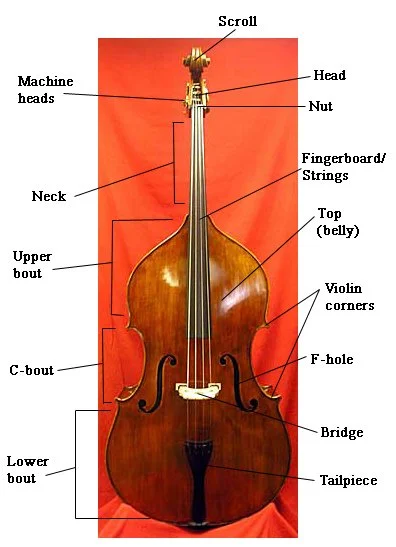

Double bass parts

So this week we're looking for instrument pieces or songs where the double bass plays a prominent role, either with a fabulous bass line, solo or a sound so integral that the song would not work without it. So this is not about the electric bass guitar, but the acoustic double bass, but of course slimmer upright touring models with pickups can also count.

So where did it all begin? Scholars argue as to whether it was originally a member of the viol or violin family but the key thing is that's it's distinctive from the other members of a orchestra or string quartet because its notes are not a fifth apart, but a fourth, those notes being E, A, D, and G, just like the bottom four notes of a guitar, and it is an octave more more lower than its cousin the cello. There are also less common five- and six-string versions, with a higher C and/or a lower B. Bass players often read sheet music that shows the notes to be an octave higher because the actual notes they play would disappear below the staff.

The double bass is a highly versatile instrument, with a whole range of sounds from bowing (arco) and plucking (pizzicato) finger techniques with a variety of French and Italian names, such as, with approximate definitions, détaché (separated notes) legato (smooth) staccato (short and sharp) spiccato (bounced with the bow, martelé (hammered) tremolo (trembling by pressing and wobbling fingers), sautillé (played rapidly in the middle of the bow) and many more.

There's no need to identify these techniques individually but it would be good to have a range of double bass sounds across nominations.

Alcoa aluminium version …

These techniques are also used on the cello, but the bass, not only deeper in pitch, tends to have strings get a particularly strong thwacking, originally with gut strings, but often also nylon in later instruments. Bass string plucking had a distinctive thumping sound in the early 20th century jazz and more of a twanging a rockabilly and 1950s rock’n’roll arrived.

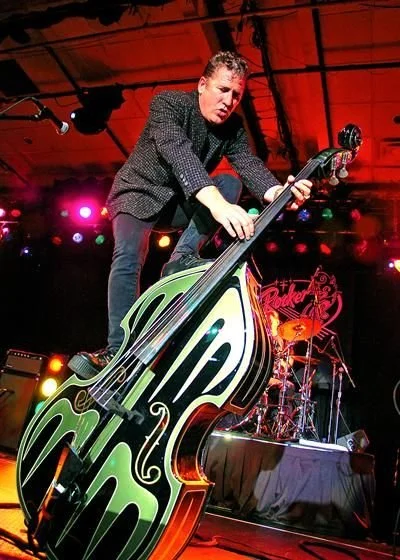

The double bass as a classical instrument may be associated with a more genteel performance style, but when I first moved to London, I caught a rockabilly band in a Hackney venue sadly no longer in existence, called The Trolley Stop, which featured a circular snooker table. But during one performance, the bass player, particularly vigorous and with the excitable technique of standing on the corners next to instruments’ F-hole, thwacked his strings so violently that the neck snapped and the whole instrument exploded in a chaos of spruce, steel, arms, legs, nylon and maple.

The standing technique can go horribly wrong …

Joseph Haydn is thought to have written the first concerto for double bass in 1763, but there’s a huge range since, with many of the most famous composers, including Beethoven and Mozart letting it get the occasional limelight, as well as Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf, Johann Baptist Vanhal, Franz Anton Hoffmeister, Leopold Kozeluch, Anton Zimmermann, Antonio Capuzzi, Wenzel Pichl and Johannes Matthias Sperger.

The 18th century also saw many stars of the instrument, including Josef Kämpfer, Friedrich Pischelberger, Johannes Mathias Sperger and Johann Hindle, but the biggest pioneer who really put it on the map, who revolutionised bowing and fingering techniques and standardised the fourths tuning, was the eccentric, colourful Italian Domenico Dragonetti.

Domenico Dragonetti (left) in 1843 with Robert Lindley and Charles Lucas

Dragonetti (1763–1846) changed double bass forever. He used a different Italian bow with an unusual outward curve and was much shorter (50cm) than the typical straight bow used by French or other players. This, along with his personality, gave him the extra drive to play complicated passages with clarity and volume, and he became the Paganini of instrument, influencing all around him. Carlo Lipinski, a famed cellist of his day described it as ‘fuoco celeste’ (divine fire).

Dragonetti’s revolutionary ‘overhand’ technique, leaning over the instrument to press the strings with more control and power, also gave him a sound like no other player, a style, he said let the player be “the true mediator of taste and expression”.

Dragonetti was the first of a whole line of great virtuoso players, including Giovanni Bottesini (1821–1889) Franz Simandl (1840–1912), Edouard Nanny (1872–1943). Serge Koussevitzky (1874–1951), leading all way up to 20th-century greats François Rabbath, Gary Karr, and Edgar Meyer.

Charles Mingus

But of course the other great strand of the players belongs to he jazz world, from which there are many to use as stating points, from Willie Dixon to Jimmie Blanton, Ray Brown to the great avant-garde Dane Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen, not to mention that giant Charles Mingus, as much known for his compositions and social campaigning as his bass playing, Bob Cranshaw, who played with saxophonist Sonny Rollins, and virtuosos of the electric bass who have commonly crossed over into the upright – Jaco Pastorius and Stanley Clarke.

Jimmie Blanton, for example, was known for his great solos, but upright is the beating heart of the lower register and has an integral role as a complementary instrument. Let’s hear from Ray Brown about how that work best:

But for further inspiration, let’s have some solo samples from Willie Dixon, Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen, and contemporary player Nenad Vasilic, here showing off the sheer beauty of instrument, with slow-motion string wobble and the piece "Ti bi hteo pesmom da ti kazem” somehow also drowning out and transcending the noise of motorway traffic.

Finally though, there’s also room, if you can find examples, for alternative upright bass instruments from other cultures, such as the Mongolian box-shaped, throat-singing accompaniment Ikh khnurr, recently highlighted as a Word of the Week entry,

Or the extraordinary sight and sound of the octobass or octobasse, that rare, extra big monster version of the double bass, first built in 1850 in Paris by the French luthier Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume (1798–1875). A specimen in the collection of the Musée de la Musique in Paris measures a whopping 3.48 metres (11 ft 5 in) in height, and comes with levers to control the strings.

Here’s a demonstration of the instrument that makes a sound so low it’s like a bellowing elephant in a bad mood first thing in the morning and you can see the vibration of the strings, almost in its own dimension.

So then, how low can you go? Conducting the orchestra this week with your nominations is the excellent Loud Atlas! Please suggest your songs or pieces in comments below for deadline on Monday at 11pm UK time and playlists published next week. It’s all about the bass …

New to comment? It is quick and easy. You just need to login to Disqus once. All is explained in About/FAQs ...

Fancy a turn behind the pumps at The Song Bar? Care to choose a playlist from songs nominated and write something about it? Then feel free to contact The Song Bar here, or try the usual email address. Also please follow us social media: Song Bar Twitter, Song Bar Facebook. Song Bar YouTube, and Song Bar Instagram. Please subscribe, follow and share.

Song Bar is non-profit and is simply about sharing great music. We don’t do clickbait or advertisements. Please make any donation to help keep the Bar running: