By The Landlord

“Breathless waltzes have only ever led girls into trouble.” – Sarah MacLean

"It is a real piece of art if you can make a waltz sound like it is the easiest piece of music to play, because it's really not." – André Rieu, Dutch violinist and composer

“Here ([n Vienna] waltzes are called works! And Strauss and Lanner, who play them for dancing, are called Kapellmeistern. This does not mean that everyone thinks like that; indeed, nearly everyone laughs about it; but only waltzes get printed.” – Frédéric Chopin

They say things come in threes, and that's often bad stuff. Only three? Where might we begin to choose from that list at the moment? We're certainly living in uncommon times, so perhaps this is as good a week as any to step out of what's known as musical common time, in other words four beats to the bar, or any related equivalent (eight or sixteen beats) one that has been the dominant rhythmic signature for western song and instrumental work to an alternative. Instead then, let's take different steps, not necessarily to dance in posh clothes, but to approach the movement of a song with another rhythm entirely. It’s rarer, but when you look into it, it's surprising how many famous songs use it. Not sure? It’s as straightforward as one, two, three …

It doesn't take much, if any music skill to spot a song in 3/4 or 6/8 time signature. You can just count on it, and feel it, whether fast or slow. And there is something differently pleasing about threes. Three things is a rhetorical device. The rule of three is a writing principle that suggests that a trio of events or characters is satisfying to the ear, more humorous or effective than other numbers – a perfect number as it’s said in Latin - “omne trium perfectum”. Three little birds; three little pigs; veni, vidi, vici (came, saw, conquered); shake, rattle’n’ roll; work, rest and play, higher, faster, stronger, liberté, égalité, fraternité, slip-slap-slop.

The waltz, the most obvious of three-time signature styles, derives its name from the German verb walzen, to roll. There’s something rather modern about that. So it has a natural movement to it, a rolling, swinging form of dance. It became a particularly popular form in the early 19th century. Franz Schubert, who in his prolific but short life wrote in many forms, included many waltzes such as the valses sentimentales and valses nobles, but they weren’t intended as serious pieces of music, just as something to dance and jig around with at home.

Frédéric Chopin had a different view. There are 18 surviving waltzes (five of which wrote as a child), along with his mazurkas and polonaises, also in the 3/4 time signature, and they were clearly not intended for dance and intended as serious compositional genres. Brahms, Ravel and Shostakovich are among many who adopted the waltz for higher-minded works.

Chopin also used the mazurka, from cultural region of Mazovia in Poland, to develop compositions from the rhythms of a Polish folk dance in triple meter, usually at a lively tempo – "strong accents unsystematically placed on the second or third beat".

Waltzes very much became the equivalent of rock’n’roll during early 19th-century Vienna, popularised in particular by Johann Strauss (the first) and Joseph Lanner, who was the equivalent of a dance band conductor. Another 19th-century figure, German Bohemian music critic Eduard Hanslick said of the time: "You cannot imagine the wild enthusiasm that these two men created in Vienna. Newspapers went into raptures over each new waltz, and innumerable articles appeared about Lanner and Strauss." The waltz was the way high society could get together and, at least in dance form, get it on.

Chopin meanwhile was appalled at the cheap popularism of the genre presented in this way: “Among the numerous pleasures of Vienna the hotel evenings are famous. During supper Strauss or Lanner play waltzes...After every waltz they get huge applause; and if they play a Quodlibet, or jumble of opera, song and dance, the hearers are so overjoyed that they don't know what to do with themselves. It shows the corrupt taste of the Viennese public,” he said with disgust.

But perhaps the most famous of all waltzes is not by the first Johann Strauss, but his son of the same name, who wrote The Blue Danube, originally "An der schönen, blauen Donau” in 1866. Strauss II really picked up the baton from his father and went for it. He composed over 500 waltzes, polkas, quadrilles, and other types of dance music, as well as several operettas and a ballet. And he had a quite fabulous beard too, another rocker of his day.

Johann Strauss II - beard and Blue Danube

Famous waltzes pieces have become popularised in many ways but perhaps most effectively in film. "I began to write a kind of waltz and in a little more than an hour I had the theme written,” said Maurice Jarre, the French composer of all the scores of David Lean's films from Lawrence of Arabia (1962) onwards, as well as scores for other directors including for The Train (1964) and those blockbusters Witness (1985), Fatal Attraction (1987) and Ghost (1990).

It’s almost impossible again to ignore the work of Stanley Kubrick in relation to film music, and it’s used to dazzling effect in how space craft and planetary bodies move in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968):

Perhaps even more astonishing is how Chopin’s Waltz Op. 64 No. 2 here:

… is used in the 1982 animated film Waltz With Bashir, to evoke a dance of death by a solider in the Lebanon War.

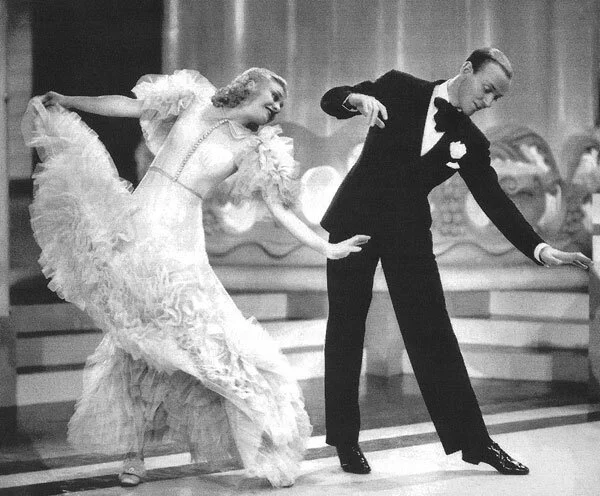

But in all films, perhaps the most dazzling use, and also subversion of the genre is by Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers in 1936’s Waltz in Swing Time, where in one sequence they take the standard waltz with music by Jerome Kern, speed it up, and add in lots of extra cross rhythms and tap. Ginger did all the same as Fred, but also backwards and in heels. Sheer genius.

The waltz and other three-four time signature versions were also taken up by many great songwriters of the early 20th century, such as Eric Coates, Robert Stolz, Ivor Novello, Richard Rodgers and Cole Porter. This was in many ways riding of the previous century’s first wave of pop music.

Jazz meanwhile did flirt with the waltz, but more often went its own way. There were popular piece such as the Missouri Waltz by Dan and Harvey’s Jazz Band (1918) and the "Jug Band Waltz" or the "Mississippi Waltz" by the Memphis Jug Band (1928), but jazz musicians preferred four or eight or 16 beats the bar, known as duple time, for the next few decades. But then came Thelonious Monk’s recording of Carolina Moon in 1952 and Sonny Rollins’s Valse Hot in 1956), taken up the triple meter for a whole new era of jazz.

But as well as waltzes, minuets, scherzi, polonaises, mazurkas, not to mention other more modern genres, from pop to R&B and country & western ballads, there are also international genres such as sega, a genre of Mauritius, with origins in the music of slaves as well as their descendants Mauritian Creole people and there are now cross-genres such as the reggae-influenced seggae.

But as far as the songs that most commonly up in our weekly themes, it’s quite surprising that while the four-time signature dominates, waltz is also employed occasionally by a whole spectrum of very contrasting artists. Joni Mitchell once dismissed the genre: “White rhythm is waltzes, marches, and the polka. In Africa, rhythm is used for a celebratory groove, but white rhythm doesn't have such an enormous vocabulary of spirits. It's basically militant,” she said, rather angrily, but waltzes or at least the three-four time signature is certainly not restricted to the polka-dancing white folks.

From soul to rock, folk to gospel, metal to dance to punk and postpunk, it’s a form that has been used by artists as diverse as Joan Armatrading to Fiona Apple, Kate Bush to James Brown to Jeff Buckley, Leonard Cohen to The Clash to Cocteau Twins, Nick Drake to Bob Dylan, Elvis Presley to Elliott Smith, Echo and the Bunnymen, Fleet Foxes to Fairport Convention, Grateful Dead to Go-Betweens, Jimi Hendrix to Irma Thomas, Billy Joel to Joy Division, Led Zeppelin to Lynyrd Skynyrd to LCD Soundsystem, Mystery Jets, Mamas & The Papas to and Metallica to Moody Blues, Nina Simone and Nirvana to Otis Redding, Queens of the Stone Age to Radiohead, The Smiths, Siouxsie and the Banshees to Sly and The Family Stone, Richard Thompson to Traffic and Tindersticks, U2 to Vashti Bunyan, Jack White, who incidentally is obsessed with the number three and his Third Man Records label,Townes Van Zandt to Frank Zappa.

So then, before the dance begins, here are a few examples of songs and music already picked for A-lists for other topics, that use the three-four time signature. How about John Barry's brilliant Midnight Cowboy with Toots Thielemans on the harmonica?

And connected to a song in that film, here’s another by Fred Neil, with Dolphins.

Neil was a huge influence on Jeff Buckley, not only style but also time signature.

But perhaps there are none greater in delivery than Aretha Franklin, here with (You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman, written by the great team of Carole King and Gerry Goffin:

Al Stewart is also fond of the waltz time signature, here also including three elements into the bargain, previously chosen for a theme about that particular number in other contexts. The Three Mules are allegorical manifestations for the political figures of Ramsey, Stanley and Neville:

Going across the pond now, the beautiful movement of America by Simon & Garkunkel:

And who would have thought that Lou Reed would use a waltz rhythm? Slowly but surely he does with Perfect Day:

From one search for drugs to another, here’s that classical-style classic, Golden Brown, by The Stranglers with Dave Greenfield showing his skills on the harpsichord, doubling up into 6/8 time rather than 3/4, but also alternating into 7/8 with fiendish brilliance.

And finally, here’s a shout from me to start things off. The great David Bowie with Drive-In Saturday doing a 6/8. You can count him in anytime.

So then, it’s simply a question of one, two, three, and repeat. Taking up the conductor’s baton on this theme for the week, I’m delighted to announced the return of DJ Bear, aka Pop Off! who also has a radio show here. Place your songs in comments below for deadline this coming Monday at 11pm UK time (BST) for playlists published on Wednesday. Don’t forget … time is on your side ...

Three to the bar: a trio of regulars at the Bag of Nails pub in Bristol

New to comment? It is quick and easy. You just need to login to Disqus once. All is explained in About/FAQs ...

Fancy a turn behind the pumps at The Song Bar? Care to choose a playlist from songs nominated and write something about it? Then feel free to contact The Song Bar here, or try the usual email address. Also please follow us social media: Song Bar Twitter, Song Bar Facebook. Song Bar YouTube. Subscribe, follow and share.

Please make any donation to help keep Song Bar running: