By The Landlord

“Maps codify the miracle of existence.” – Nicholas Crane, Mercator: The Man Who Mapped the Planet

“Give me an atlas over a guidebook any day. There is no more poetic book in the world.” – Judith Schalansky, Atlas of Remote Islands

“Men read maps better than women because only men can understand the concept of an inch equaling a hundred miles.” – Roseanne Barr

“And outside the window was like a map, except it was in 3 dimensions and it was life-size because it was the thing it was a map of.” – Mark Haddon, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time

“A map has no vocabulary, no lexicon of precise meanings. It communicates in lines, hues, tones, coded symbols, and empty spaces, much like music. Nor does a map have its own voice. It is many-tongued, a chorus reciting centuries of accumulated knowledge in echoed chants. A map provides no answers. It only suggests where to look: Discover this, reexamine that, put one thing in relation to another, orient yourself, begin here... Sometimes a map speaks in terms of physical geography, but just as often it muses on the jagged terrain of the heart, the distant vistas of memory, or the fantastic landscapes of dreams.” – Miles Harvey, The Island of Lost Maps: A True Story of Cartographic Crime

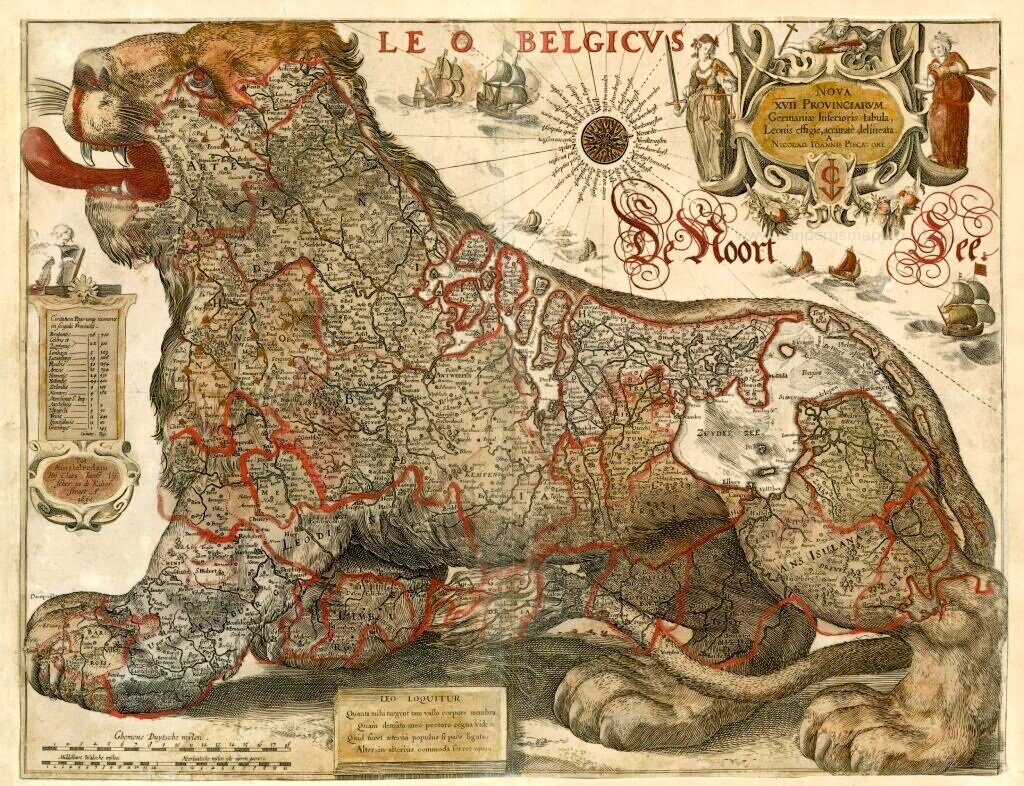

Who doesn’t love a map? I can stare at them for hours. They are meticulous, and yet metaphorical, they are recordings that stir the imagination. They are the stimulus of holidays without having to go anywhere. They are a fixed work of autocracy and discipline that also represents fantasy and adventure. They are equally absorbing as annoying. From massive old dusty atlases of the world to a crinkly, wind-flapping crinkly Ordnance Survey editions stained by tea and biscuit crumbs, from precious rare artwork maps, to out-of-date maps of past landscapes and retired streets in old bookshops, even the instantly updating screen Google versions and talking GPS, they are like life’s board game ready to roll out, offering an instant glimpse of the local and global, the historical and virtual, a perfect meeting of stay-at-home culture and terra incognita. Maps are the stimulus of stories. So, with that in mid, this week we celebrate the art of the cartographer as mentioned in song, in lyrics of evoked in music.

Probably since cave drawings or sticks in the sand, maps have been a way to understand and sense of place, of the self in the world. And in paths across the land (or sometimes the sky) within the animist belief system of Aboriginal Australians connected history, self, story and landscape in songlines or dreaming tracks.

And pictorial representations of land dates back at least 25,000 years, discovered in what is now the Czech Republic, near Pavlov, carved on a mammoth tusk. But in about 600BC the first known formal map was created, the Imago Mundi, or the Babylonian Map of the World. The Babylonians map maps on tablets. The Greeks of course added more, and another great landmark work in Roman times was that of Ptolomy and and mapa mundi from his Geographica, a crucial form of reference until the Middle Ages. Ptomoly’s maps were highly influential, but as a pioneer, he also got things hopelessly wrong, as this 15th-century reconstruction shows.

Ptolomy’s pioneering mapa mundi. Not a bad effort, but a few errors

But at the same time works were also being created in China, like this rather beautiful colour one of the country by Da Ming Hun Yi Tu, dating from about 1390:

Da Ming Hun Yi Tu’s China, dating from about 1390.

As Louise Penny puts it, in A Great Reckoning: “Maps gave humans control over their surroundings, for the first time ever. It sounds simple now, but a thousand years ago it would have been an incredible feat of imagination and imagery. All maps are drawn as though looking down. From a bird's point of view. From their god's point of view. Imagine being the first person to think of that. To be able to wrap their minds around a perspective they'd never seen. And then draw it.”

It took a long time for longitude and latitude to be corrected combined. Charles H. Hapgood writes in Maps of the Ancient Sea Kings: Evidence of Advanced Civilization in the Ice Age: “It was in the 18th century that we first developed a practical means of finding longitude. It was in the 18th century that we first accurately measured the circumference of the earth. Not until the 19th century did we begin to send out ships for purposes of whaling or exploration into the Arctic or Antarctic Seas. The maps indicate that some ancient people may have done all these things.”

Maps represent power and change in the world, as brought about by an understanding of what is where and how to get it. “Wars of nations are fought to change maps. But wars of poverty are fought to map change,” said the great Muhammad Ali. “If geography is prose, maps are iconography,” said Lennart Meri, the Estonian politician, writer, and film director.

And at the time his own revolution, Poland’s Lech Walesa foresaw a European Union, or at least some concept of globalisation: “Tomorrow there will be no division to Europe and Asia. These are old concepts that would remain only on maps. Everything will be united. Companies will be united. It is a process of structures growing due to the technological progress.”

But as much as as tools of power, maps also have a significant effect on the psyche of individuals.

Charles Darwin found particular pleasure in map creation on his travels. “There are several other sources of enjoyment in a long voyage, which are of a more reasonable nature. The map of the world ceases to be a blank; it becomes a picture full of the most varied and animated figures. Each part assumes its proper dimensions: continents are not looked at in the light of islands, or islands considered as mere specks, which are, in truth, larger than many kingdoms of Europe. Africa, or North and South America, are well-sounding names, and easily pronounced; but it is not until having sailed for weeks along small portions of their shores, that one is thoroughly convinced what vast spaces on our immense world these names imply,” he writes in Voyage of the Beagle.

In Gerald Durrell’s My Family and Other Animals, he reminisces about how "maps that lived, maps that one could study, frown over, and add to; maps, in short, that really meant something.” Maps are important to us.

“My first kiss was in the geography room, where you put all the maps,” says Marion Cotillard, French actress and singer-songwriter.

“I've always been fascinated and stared at maps for hours as a kid. I've especially been most intrigued by the uninhabited or lonelier places on the planet. Like Greenland, for instance, or just recently flying over Alaska and a chain of icy, mountainous islands, uninhabited,” says Andrew Bird.

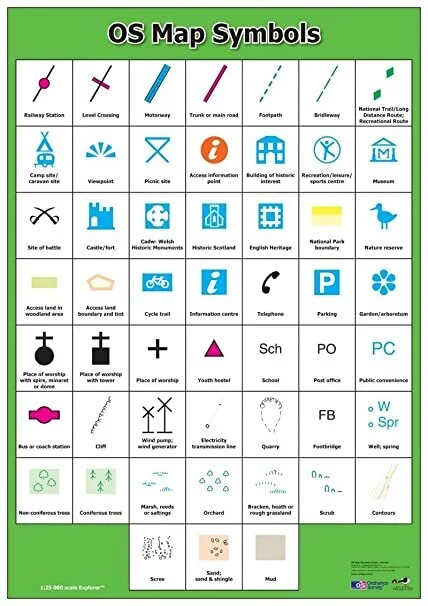

The wondrous world of OS symbols

Prolific travel writer Bill Bryson particularly loves the Ordnance Survey series as he recalls in Notes from a Small Island:

“Coming from a country where mapmakers tend to exclude any landscape feature smaller than, say, Pike’s Peak, I am constantly impressed by the richness of detail on the OS 1:25,000 series. They include every wrinkle and divot of the landscape, every barn, milestone, wind pump and tumulus. They distinguish between sand pits and gravel pits and between power lines strung from pylons and power lines strung from poles. This one even included the stone seat on which I sat now. It astounds me to be able to look at a map and know to the square metre where my buttocks are deployed.”

He probably also took a trip to Stanfords, the king of map shops in London, an emporium of every edition you’d ever need.

Maps are clearly also great stimulus for the brain and in gaining general knowledge. Super-nerd Ken Jennings is the highest-earning American game show contestant of all time. He reckons maps were a vital part of his education: “Even before you understand them, your brain is drawn to maps. I would stare at maps of Delaware for hours. There's just something hypnotic about maps. For me, it started as a child with one of those little wooden jigsaw maps of the US, where's there's crocodiles on Florida and apples on Washington state. That was my very first map.”

Maps have practical uses that range from the individual to mass communities. Roisin Murphy has popped in the bar to confess that she’s utterly useless with conventional maps, but “I use maps in my phone a great deal because I can't tell left from right. Having easy access to maps has given me a completely different life. When I first moved to London, I couldn't get anywhere and spent so much money on cabs because I couldn't figure it out.”

But maps aren’t just for flitting about a city. They can also save lives. “New flood maps in many states have raised the estimation of flood risks along rivers, streams and oceans, adding many properties to flood zones for the first time,” says Bill Dedman, the Pulitzer Prize-winning American journalist. Here’s an early example then, at the same time being rather beautiful:

Art and fact combined. Mississippi River flooding over time, by Harold N. Fisk, 1944

Google maps have taken over our lives. If you’re ever driving and want to avoid congestion, the chances are that it can gather information where where GPS numbers are building up.

Google’s Eric Schmidt tells us: “We know that Google Earth and Google Maps have had a tremendous impact on Google traffic, users, brand, adoption, and advertisers. We also know Google News, for example, which we don't monetize, has had a tremendous impact on searches and on query quality. We know those people search more. Because we've measured it.”

But it’s a double-edged sword of data collection. “As people talk, text and browse, telecommunication networks are capturing urban flows in real time and crystallizing them as Google's traffic congestion maps,” says Carlo Ratti.

And a word of caution from historian and author Yuval Noah Harari: “Take Google Maps or Waze. On the one hand, they amplify human ability - you are able to reach your destination faster and more easily. But at the same time, you are shifting the authority to the algorithm and losing your ability to find your own way.”

But while we travel this map towards song, maps are also tremendous stimulus for writing. We’ve got several writers in the Bar today to tell us why:

“A story is a map of the world. A gloriously colored and wonderful map, the sort one often sees framed and hanging on the wall in a study full of plush chairs and stained-glass lamps: painstakingly lettered, researched down to the last pebble and participle, drawn with dash and flair, with cloud-goddesses in the corners and giant squid squirming up out of the sea...[T]here are more maps in the world than anyone can count. Every person draws a map that shows themselves at the center,” say Catherynne M. Valente, in The Boy Who Lost Fairyland.

Nova Totius Terrarum Orbis Tabula by Hendrik Hondius, 1630

“Writing has nothing to do with meaning. It has to do with landsurveying and cartography, including the mapping of countries yet to come, says Gilles Deleuze.

Author Charles Frazier describes how, “while writing 'Cold Mountain,' I held maps of two geographies, two worlds, in my mind as I wrote. One was an early map of North Carolina. Overlaying it, though, was an imagined map of the landscape Jack travels in the southern Appalachian folktales. He's much the same Jack who climbs the beanstalk, vulnerable and clever and opportunistic.”

“A map does not just chart, it unlocks and formulates meaning; it forms bridges between here and there, between disparate ideas that we did not know were previously connected,” says Reif Larsen, in his book The Selected Works of T.S. Spivet.

Maps power the imagination, especially when they hint at the unknown. “Mental maps. Maps with edges. And for Auden, for so many of us, it’s the edges of the maps that fascinate …” says David Mitchell in The Bone Clocks.

Map creation is often not merely about accuracy or reality, but also fantasy. Two hugely successful authors in that realm are also in the Bar:

“Map-making had never been a precise art on the Discworld. People tended to start off with good intentions and then get so carried away with the spouting whales, monsters, waves and other twiddly bits of cartographic furniture that the often forgot to put the boring mountains and rivers in at all,” says Terry Pratchett, reading from Moving Pictures.

“It seems a great big hole to me,” squeaked Bilbo (who had no experience of dragons and only of hobbit-holes). He was getting excited and interested again, so that he forgot to keep his mouth shut. He loved maps, and in his hall there hung a large one of the Country Round with all his favourite walks marked on it in red ink. “How could such a large door be kept secret from everybody outside, apart from the dragon?” he asked. He was only a little hobbit you must remember,” says J.R.R. Tolkien, opening a copy of The Hobbit, also subtitled There and Back Again. And while we’re here, let’s get a glimpse of Middle Earth:

A map of the imagination. Middle Earth by JRR Tolkein

Maps are also inside the brain, as much of a psychological sense of place as a cartographic one. Memory works like a map too. The Czech psychiatrist Stanislav Grof says: “Ancient eschatological texts are actually maps of the inner territories of the psyche that seem to transcend race and culture and originate in the collective unconscious.”

“Regular maps have few surprises: their contour lines reveal where the Andes are, and are reasonably clear. More precious, though, are the unpublished maps we make ourselves, of our city, our place, our daily world, our life; those maps of our private world we use every day; here I was happy, in that place I left my coat behind after a party, that is where I met my love; I cried there once, I was heartsore; but felt better round the corner once I saw the hills of Fife across the Forth, things of that sort, our personal memories, that make the private tapestry of our lives,” says Alexander McCall Smith in Love Over Scotland.

“We're all pilgrims on the same journey - but some pilgrims have better road maps,” chips in Nelson DeMille.

Maps then are a key to a sense of self. Pick up a map covering a large area, and perhaps the first thing you’ll try to identify is where you are, or where you live. Through our maps, we willingly become a part of their boundaries. If our home is included, we feel pride, perhaps familiarity, but always a sense that this is ours. If it is not, we accept our roles as outsiders, though we may be of the same mind and culture. In this way, maps can be dangerous and powerful tools,” says Debbie Lee Wesselmann, author of Trutor & The Balloonist.

And here’s a poem by Lisel Mueller, from Alive Together, capturing the inner map:

A map of the world. Not the one in the atlas,

But the one in our heads, the one we keep coloring in.

With the blue thread of the river by which we grew up.

The green smear of the woods we first made love in.

The yellow city we thought was our future.

The red highways not traveled, the green ones

With their missed exits, the black side roads

Which took us where we had not meant to go.

The high peaks, recorded by relatives,

Though we prefer certain unmarked elevations,

The private alps no one knows we have climbed.

The careful boundaries we draw and erase.

And always, around the edges,

The opaque wash of blue, concealing

The drop-off they have stepped into before us,

Singly, mapless, not looking back.”

Maps most importantly encourage adventure within us. “Maps encourage boldness. They’re like cryptic love letters. They make anything seem possible,” says author Mark Jenkins

“Once, centuries ago, a map was a thing of beauty, a testament not to the way things were but to the heights scaled by men's dreams,” says Bea González in Mapmaker's Opera.

“When we allow ourselves to explore, we discover destinations that were never on our map,” says Amie Kaufman, in Unearthed

“Uncharted territory,” I said. “The parts on the maps of our lives that we don’t understand. In cartographer’s language they call these places sleeping beauties, is how Christopher Barzak likes to put it, in The Love We Share Without Knowing.

“Well,” says Jennifer Zeynab Joukhadar in The Map of Salt and Stars: “The most important places on a map are the places we haven't been yet.”

“I speak to maps. And sometimes they something back to me. This is not as strange as it sounds, nor is it an unheard of thing. Before maps, the world was limitless. It was maps that gave it shape and made it seem like territory, like something that could be possessed, not just laid waste and plundered. Maps made places on the edges of the imagination seem graspable and placable,” recounts Abdulrazak Gurnah, in By the Sea.

“When a thing beckons you to explore it without telling you why or how, this is not a red herring; it’s a map,” says Gina Greenlee, in Postcards and Pearls: Life Lessons from Solo Moments on the Road.

“A labyrinth is a symbolic journey . . . but it is a map we can really walk on, blurring the difference between map and world,” says Rebecca Solnit in Wanderlust: A History of Walking.

But can maps also take away our spirit of adventure?

“Consulting maps can diminish the wanderlust that they awaken, as the act of looking at them can replace the act of travel. But looking at maps is much more than an act of aesthetic replacement. Anyone who opens an atlas wants everything at once, without limits--the whole world. This longing will always be great, far greater than any satisfaction to be had by attaining what is desired. Give me an atlas over a guidebook any day. There is no more poetic book in the world,” says Judith Schalansky, in Atlas of Remote Islands, giving a balance to the argument.

The joyously informative: Comparative Heights of the Principal Mountains and Lengths of the Principal Rivers in the World by William Darton and W. R. Gardner, 1823

But some writers, and explorers are contradictorily against maps.

“For the execution of the voyage to the Indies, I did not make use of intelligence, mathematics or maps,” boasted Christopher Columbus.

Maps are inevitably flawed of course, just like people. “Maps are living, breathing organisms that change on a daily basis: You see it in new roads, bridge closures, and demolitions, says Noam Bardin.

And sometimes perhaps maps are no good at all. "The desert mocked the map-makers,” says Dean F. Wilson quoting from his boo, Hopebreaker.

“Life has no map; it's made of random events, always caused by something beyond your control,” adds Bangambiki Habyarimana, from Pearls Of Eternity.

John Steinbeck is also here, and he is quite scathing of map studiers: “There are map people whose joy is to lavish more attention on the sheets of colored paper than on the colored land rolling by. I have listened to accounts by such travellers in which every road number was remembered, every mileage recalled, and every little countryside discovered. Another kind of traveler requires to know in terms of maps exactly where he is pin-pointed at every moment, as though there were some kind of safety in black and red lines, in dotted indications and squirming blue of lakes and the shadings that indicate mountains. It is not so with me. I was born lost and take no pleasure in being found, nor much identification from shapes which symbolize continents and states.”

But let’s now wind up our cartographic journey with some inspiration from fiction to film and music. Maps play a key role in many film plots as well as books, particularly in children’s adventure works, from Stevenson’s Treasure Island to The Da Vinci Code, from Indiana Jones and Harry Potter to Wes Anderson’s Moonrise Kingdom, to more adult tales of greed and hidden treasure such as the Bogart classic The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. But my favourite is the Monty Python-related Time Bandits, in which a bunch of dwarfs steal the map of the Supreme Being, taking a small boy on a fantastic ironic adventure.

Finally though, some musical examples to set us on our path. There are many songs about maps specifically, but maps can also come into play in passing lyrical moments. Here, in a song previously chosen for another topic, is Joni Mitchell, with A Case of You:

On the back of a cartoon coaster

In the blue TV screen light

I drew a map of Canada

Oh, Canada

With your face sketched on it twice

However, some things can’t be mapped at all. Björk reckons Human Behaviour is one of them:

Human behaviour …

And there's no map

And the compassWouldn't help at all

Lastly, a lesser known number, and an example of how an instrumental can be evocative of the whirls and swirls, lines and contours, as shown by electronica artist Luke Abbott with his Hand Drawn Maps:

So then, X marks the spot, but where do you start digging? Chief cartographer this week, I’m delighted to say is that brave pioneer of musical playlists, the man sometimes known as sonofwebcore, the great and generous George Boyland. Please place your map related songs in comments below for last orders on Monday 11pm UK time, for playlists published on Wednesday. So, who has the coordinates?

“A map has no vocabulary, no lexicon of precise meanings. It communicates in lines, hues, tones, coded symbols, and empty spaces, much like music”

New to comment? It is quick and easy. You just need to login to Disqus once. All is explained in About/FAQs ...

Fancy a turn behind the pumps at The Song Bar? Care to choose a playlist from songs nominated and write something about it? Then feel free to contact The Song Bar here, or try the usual email address. Also please follow us social media: Song Bar Twitter, Song Bar Facebook. Song Bar YouTube. Subscribe, follow and share.

Please make any donation to help keep Song Bar running: