By The Landlord

“The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.”

― George Bernard Shaw

Picture this. Aliens have landed on Earth. They are hovering in giant impenetrable monolith-like ships across the planet. Will they attack? Do they want to talk? Can they talk? What will they say? What do they even look like? The military might of the superpowers are braced. So what do they do? Brandish weapons, of course. Eventually, after a period of confusion and stalemate, they call in a language expert. And so a perilous dialogue begins …

This is the setting of a new sci-fi movie, Arrival, which, refreshingly, deals with some interesting ideas, including the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, originating from linguist and fire prevention officer Benjamin Lee Whorf (1897-1941), whose thesis was that the language we use shapes our ideas, thought processes, actions, and therefore our identities. Is it true? Does the mechanical nature of the German language make that nation more practical and logical? Does the flamboyance of Italian make the Italians excessive, gesticulatory, and romantic? Do some of the Nigerian languages sound angry and therefore induce rage? Does English make us more like … shopkeepers?

Here we are getting into dubious stereotyping territory, but Whorf’s research reveals some interesting reflections. He found that the Hopi, a Native American tribe, have a language that contains no reference to time, no reference to past or future. Imagine how that might affect your lifestyle and identity. Could be a bit inconvenient when it comes to making a doctor’s appointment or working 9 to 5: “Sorry boss, just a bit of a misunderstanding there. My language has no word for work.” And then there are the rules for how we view the world. There are basic agreed colours, at least 11, or so it seems, but the Namibian Himba people only list five categories, and two of them, zuzu and buru both contain types of blue. Try and categorise that, Dulux. Try and give that a stupid name, Farrow & Ball. And then there’s the word for truth. Well, we think we all know what that is. But the likes of Boris Johnson and Donald Trump simply do not have a word for truth in their language. Ah, so that explains it then. It’s all been a bit of a misunderstanding.

But what causes misunderstanding in daily life, and therefore how is it illustrated in song? Lack of clarity of expression? Laziness? Poor use of language? Cultural differences? Class and background? Stupidity? Emotion? Pre-conceived ideas? Prejudice? Not listening to the other person? Only being able to see from your own perspective? The answer is all of the above. Who has not, at one time, shouted at the telly when you see people arguing, on everything from Big Brother to Jerry Springer to EastEnders, simply because they do not understand each other properly. That’s what reality TV and soap is: shite communication as entertainment. But we can also witness this in high quality literature, film and TV, where we witness the tragedy of clashing perspective, and of course the same in song.

The Jerry Springer Show. Orchestrated misunderstanding?

Everyday life is full of misunderstanding. In one evening in the pub, or in family life, even at a friendly party, even with the best intentions, between friends, and especially between partners, arguments or resentments are constantly ignited because of a careless or provocative phrase, or because of insecurity on either side: “You’ve taken it the wrong way!” But in the world of song misunderstanding can be far more nuanced. Song can express frustration or even heartbreak because for example, the songwriter can’t communicate their love properly, or it is not received in the right way, or leads to falling out with friends, mothers, fathers, brothers or sisters. But song, whether in musical collaboration, as performer or listener, is the ultimate in communication, and can evoke misunderstanding clearly, or ironically.

When I was a young man, coming from the north to the south, I used to get myself in all sorts of bother (still do at times) by my tone of voice being misunderstood. I grew up in a culture in which friends talked to each other with relentless mock cruelty and sarcasm. But coming to university and beyond, that didn’t always go down well. To mildly insult, or point out others’ insecurities or frailties, was meant as a test of intelligence, a form of compliment, a greeting, the subtext that “I like you”, but “let’s wrestle a bit”. Has anyone else had this problem? This brings me to a first song example. Mancunian and front man of I Am Kloot, John Bramwell, used to perform as solo artist Johnny Dangerously, and I fondly remember his songs then as I enjoy his later stuff. The Kloot song, Mouth On Me, looking back on his younger self, seems to touch on this very same difficulty, with characteristic tenderness:

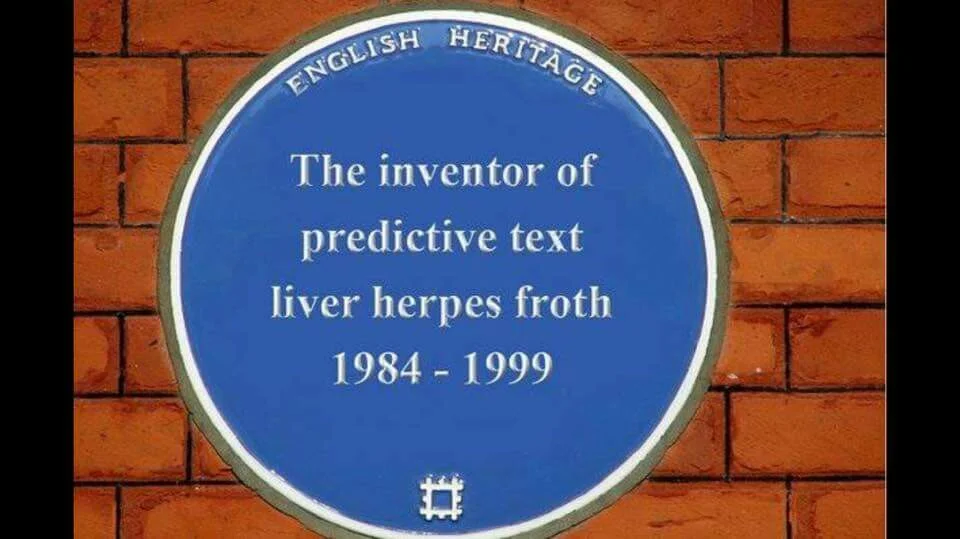

Modern life is full of the pitfalls and sinkholes of misunderstanding, and in particular irony, ironically, is one of its victims. Tone of voice is so important in communication, but the internet and emails, and even comment boxes, can be treacherous when something said in jest can be taken the wrong way. The internet, the American language of commerce, has no space for irony. So we are now compelled to use emojis, or semi-colons and brackets to convey our tone and avoid offence and ambiguity. How John Dryden, Jonathan Swift, Alexander Pope and all the greats of Grub Street must be turning in their graves at our literal banality. Talking of death, Martin King, inventor Of T9 predictive text died in 2010, and since then, without emoji, the internet announced: “That is absolutely tractor. His funfair will be hello on Sundial.” And with that a blue plaque was erected in his honour.

So let me text you something. Fancy a riot? Oh bollocks, bloody phones. Stupid technology! I actually wrote ‘fancy a pint’, but the predictive text got it wrong. It misunderstood me. But ironically (see what I died there?) as I write this, some experts have just walked into the Song Bar for a couple of jars, and join the notoriously opinionated George Bernard Shaw, to talk about this week’s topic.

“We're all islands shouting lies to each other across seas of misunderstanding,” exclaims Rudyard Kipling. “No need to shout!” shouts Shaw back at him. “Fellas, calm down,” comes a more soothing American voice. “There’s no need to misunderstand each other.” Kipling and Shaw glance at the stranger as if they are being patronised. How dare he! And who is this yank? It’s the very philosophical Henry David Thoreau. “In human intercourse the tragedy begins, not when there is misunderstanding about words, but when silence is not understood.” Hmm. There’s a quiet pause. He has a point. It’s what’s not said that is as much a source of trouble, because in that simmering space, we can all imagine something different.

The silence is then broken by a new customer. “But when you think about it,” says the writer Kevin Kelly, “we are infected by our own misunderstanding of how our own minds work.” Now everyone has gone quiet, lost in paradox. Fortunately the flamboyant figure of Charles Baudelaire sweeps into the bar. “Champagne for everyone!” he announces. “I say this. The world only goes round by misunderstanding.”

“So does that mean you are buying us a drink or not?” says everyone else, confused.

Beyond these high-profile figures, the history of the world certainly has gone round with misunderstanding and is littered with tragic, international examples. In 1170, King Henry II’s frustrated rant about Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Becket caused some thick soldiers to go and kill the clergyman. In the 1750s and with the Battle of Jumonville Glen, George Washington started a war with the French by signing a treaty he couldn’t even read, even through he made out that he understood the language. The 1854 Charge of the Light Brigade came about farcically due to miscommunication between orders indicating futility and suicide. In 1889, a massacre of Italians ensued when an agreement with the Ethiopians led to confusion over whether their emperor could or should use the Italian embassy to conduct foreign affairs, a simple confusion between optional and mandatory. Arguably on 9 November 1989, the cold war ended after a hungover East German politburo member, Gunter Schabowski, got the wrong end of the stick about visas, leading to a mass charge at the Berlin Wall. And so it goes on.

To end then, a couple of song examples to whet your appetite. We’ve already had I Am Kloot’s song about misunderstanding caused by oneself, but here’s Cher’s song on how others misunderstood her family and community of gypsies, tramps and thieves:

And to end, what better way than to have a punch-up at a wedding, where emotions, and glasses are charged:

So then, put your suggestions of songs about misunderstanding in comments below. This week’s clear-headed guest guru? I’m delighted to welcome another person making making their Song Bar debut! The super sensitive ears of Suzi will attend and understand your nominations and make up playlists next Wednesday. Deadline for suggestions? Time will be called on Monday evening. Let this be clear. After all, my intentions are good. Oh Lord, please don’t let me be misunderstood.

New to comment? It is quick and easy. You just need to login to Disqus once. All is explained in About/FAQs ...

Fancy a turn behind the pumps at The Song Bar? Care to choose a playlist from songs nominated and write something about it? Then feel free to contact The Song Bar here, or try the usual email address.