By The Landlord

“I have always imagined that Paradise will be a kind of library.” – Jorge Luis Borges

“A library is thought in cold storage.” – Herbert Samuel

“The only thing that you absolutely have to know, is the location of the library.” – Albert Einstein

“When I started the Imagination Library in my hometown, I never dreamed that one day we would be helping Scottish kids.” – Dolly Parton

“The very existence of libraries affords the best evidence that we may yet have hope for the future of man.” – T.S. Eliot

“A library is the delivery room for the birth of ideas, a place where history comes to life.” – Norman Cousins

“The library is like a candy store where everything is free.” – Jamie Ford, Songs of Willow Frost

“Doctor Who: You want weapons? We're in a library. Books are the best weapon in the world. This room's the greatest arsenal we could have. Arm yourself!” – from Doctor Who, Tooth and Claw, Season 2, written by Russell T. Davies

“I must say I find television very educational. The minute somebody turns it on, I go to the library and read a good book.” – Groucho Marx

“A library in the middle of a community is a cross between an emergency exit, a life-raft and a festival. They are cathedrals of the mind; hospitals of the soul; theme parks of the imagination. On a cold rainy island, they are the only sheltered public spaces where you are not a consumer, but a citizen instead.” – Caitlin Moran

“Ooh! I bet you've got a big one…”

Hushed monasteries for the expanding mind? Oaken cathedrals of reverential reference? Towering Babylonian staircases of spiralling mental adventure? Such may be the libraries of fantasy and imagination, and in some special havens a reality, but my first experience of one was somewhat different. When life at home got too stressful and I had to escape, when not riding my bike furiously around the park or the rainy Mersey meadows, or mooching around Woolworth's at their top 20 singles and albums section, I would sometimes park up at the local community library. There, my best mate's mum was one of several ladies behind the desk, waiting to stamp your ticket, but also, whether you wanted it or not, offer life advice. But mostly, in this most unquiet though entertaining of public spaces, they would loudly discuss their respective sex lives.

And when I approached the desk, a bit awkward and about 11 years old on the edges of puberty, it was the kind of phrase that greeted me with well-meaning friendliness, and they weren't talking about my book collection. To quote another local boy several years older than me, but who must also have frequented the place, “Caligula would have blushed.”

Meanwhile, as a part-time teacher as well as jobbing musician, my dad was an avid researcher of music of all genres, and without the funds to just buy anything he needed, his primary resource was the Manchester Music Library, an emporium of endless rows of vinyl catering every taste. Vast operatic works? Prog rock epics? Soul classics? Obscurities like a medical study of sounds of heartbeats afflicted by various diseases? They had it all.

My dad generally dived into the classical, jazz and folk sections, and I went deep into the rock and pop. Here, for a small fee (probably 5p or 10p) you could borrow a record for two weeks, and play it as much as you liked, but each came with a ticket record of all marks and scratches on the vinyl, carefully inspected by the librarian on return, and if noticeably more marked, you'd have to pay for it in full. That embedded in me a reverential respect and care for the collection.

And so, as a kid I voraciously consumed acres of vinyl and, admittedly, put some of it on cassette. Was borrowing, and sometimes taping such music, stealing it? My dad, who was extremely vigilant and virtuous about such things, didn't think so. Apparently, according to a study at the time, musicians, and authors received more from public lending rights than the paltry amount they got from record labels, and arguably that's still the case today. Many authors very much depend on PLR income more than the tiny cut of income they get from publishers.

Then, when at university, the library was not just a source of knowledge, but of vital social gathering. In the main reading and study room, with its vast dome ceiling, when any new person entered to take their place, with echoes of doors, coughs, and volumes slapping on desks, hundreds of faces would eagerly look up. It felt electrically, sexually charged, and in some of the more obscure sections of this vast building (eg. Chinese language reference section, seventh floor, rear) narrow corridors of almost never perused volumes could be the place for secret, intimate liaisons.

So then, it's time to open up volumes of songs, from referencing libraries as locations, and the knowledge therein, but also stories of visitors, encounters, librarians, subtle dramas and romances, the act of lending, borrowing and other related metaphors. So where will your browsing take you?

That’s the ticket …

Libraries have been around for hundreds, if not thousands of years, and the al-Qarawiyyin Library in Fez, Morocco, is believed to be the oldest, dating back to 859 CE, but there are many other timeless institutions, closed collections for religious scholars or wealthy merchants. The Nalanda Mahavahara was a large Buddhist monastery in the ancient kingdom of Magadha. The library there, called the Dharma Ghunj, was a center of learning from 7th Century BCE to about 1200 CE. The library at Saint Catherine’s Monastery at the foot of Mount Sinai, Egypt, opened somewhere between 548 – 565 CE, or the Imperial Library of Constantinople of the Byzantine Empire, thought to be the last great library of the ancient world, founded by Constantius II during his reign 337 – 361 CE.

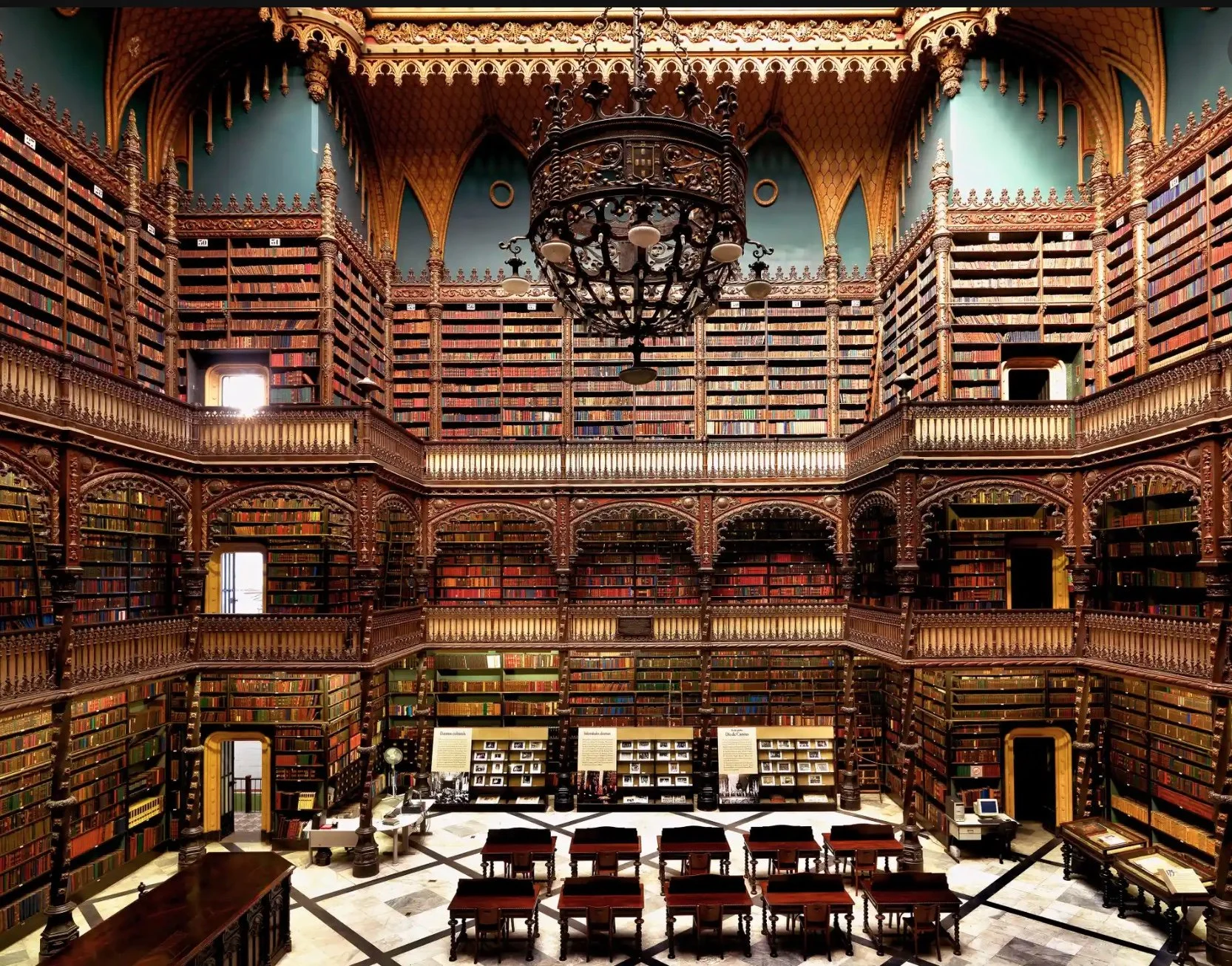

This week’s topic could centre on huge private collections, but the dynamics of songwriting are far more likely to be inspired by the public library. There are great university libraries such as Oxford University’s Bodleian, the beautiful building at Trinity College Dublin, or others around the world, but an example of a public building that had a very significant effect on society came in was established in 1653 under the will of Humphrey Chetham (1580–1653), for the education of "the sons of honest, industrious and painful parents.” Manchester’s Chetham’s library is the oldest free public reference library in the English-speaking world and was a regular place of study for Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in the 19th century.

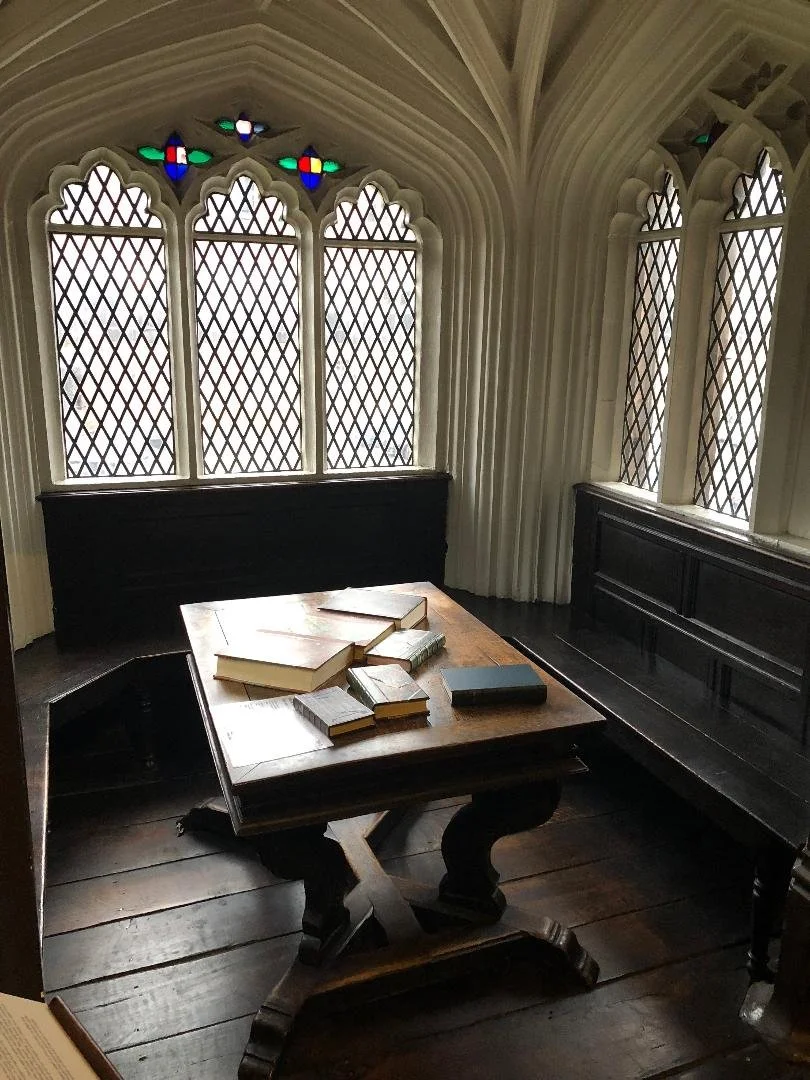

The alcove in which Marx and Engels worked at Chetham’s library. Opened in 1653, it’s the oldest free public reference library in the English-speaking world

Libraries have been a huge inspiration to authors and songwriters in their personal development. Dolly Parton has used some of her wealth to open Imagination Libraries for children across the world.

When I visit my local library now, to borrow something, or use their photocopier, I see loads of kids doing their homework, or just using it as a haven, as it’s likely they don’t have space or quiet at home. “As a child, I spent a lot of time at the library,” says Tracy Chapman.

“I read all the time. I love it. My fantasy would be to be locked into a library. I'd be very, very happy,” says Pink, who is also in our Bar today, perusing the bookshelves.

AC/DC’s Angus Young struts up and down too, and explains that “Because we grew up in Australia, to find information about a lot of blues guys, I used to go to the library and find the jazz magazines. They didn't even sell them at the time in news agents.”

For some, libraries just became a wonderful haven to indulge in the written word and develop your vocabulary. “Between the ages of fifteen and twenty-four, I must have read a whole library,” adds Charles Bukowski. And in his memoirs Malcolm X recounts how educated himself in the prison library.

Sue Townsend also describes how the borrowing system forced her to focus on reading. “We had library books in our house, but not our own. So you had 14 days to read them. There would be eight books a fortnight in our house and I'd read as many of those as I could.”

“I couldn't go to college, so I went to the library three days a week for 10 years. I discovered me in the library. I went to find me in the library,” adds Ray Bradbury.

And another sci-fi giant, Isaac Asimov, recounts their importance in his upbringing. “My real education, the superstructure, the details, the true architecture, I got out of the public library. For an impoverished child whose family could not afford to buy books, the library was the open door to wonder and achievement, and I can never be sufficiently grateful that I had the wit to charge through that door and make the most of it. Now, when I read constantly about the way in which library funds are being cut and cut, I can only think that the door is closing and that American society has found one more way to destroy itself.”

Again and again we hear how important they are but also underfunded and under threat.

P. J. O’Rourke meanwhile laments the decline of the physical space being replaced by the internet. “The library, with its Daedalian labyrinth, mysterious hush, and faintly ominous aroma of knowledge, has been replaced by the computer's cheap glow, pesky chirp, and data spillage.”

And yet arguably Wikipedia and the internet at its best, is surely also one of the most democratic forms of library available. As Peter Singer put it: “If we can put a man on the moon and sequence the human genome, we should be able to devise something close to a universal digital public library.”

“Information helps you to see that you're not alone … The library helps you to see, not only that you are not alone, but that you're not really any different from everyone else,” adds Maya Angelou.

“A library is not a luxury but one of the necessities of life,” wrote Henry Ward Beecher.

“Libraries store the energy that fuels the imagination. They open up windows to the world and inspire us to explore and achieve, and contribute to improving our quality of life. Libraries change lives for the better,” says Sidney Sheldon.

“I go into my library and all history unrolls before me,” says Alexander Smith.

And here’s Doris Lessing expanding on how vital they are for society: “A public library is the most democratic thing in the world. With a library you are free, not confined by temporary political climates. No one - but no one at all - can tell you what to read and when and how. What can be found there has undone dictators and tyrants: demagogues can persecute writers and tell them what to write as much as they like, but they cannot vanish what has been written in the past, though they try often enough...People who love literature have at least part of their minds immune from indoctrination. If you read, you can learn to think for yourself.”

But as well as public spaces, they are also private ones. Here’s Paul Auster, author of the New York trilogy in which public libraries also play a part. ““Libraries aren't in the real world, after all. They're places apart, sanctuaries of pure thought. In this way I can go on living on the moon for the rest of my life.”

But not everything always goes to plan in these institutions. Books get stolen, lost or misplaced. Some songs might use this as a hook for a story in their lyrics. There are many examples of books being returned after decades with record fines, but perhaps the longest is a copy of Charles Darwin’s Insectivorous Plants finally returned to Sydney library after more than a century had passed. It was borrowed in 1889 and returned in 2011.

Hilary Mantel, the brilliant author of the Wolf Hall trilogy, admits: “I once stole a book. It was really just the once, and at the time I called it borrowing. It was 1970, and the book, I could see by its lack of date stamps, had been lying unappreciated on the shelves of my convent school library since its publication in 1945.”

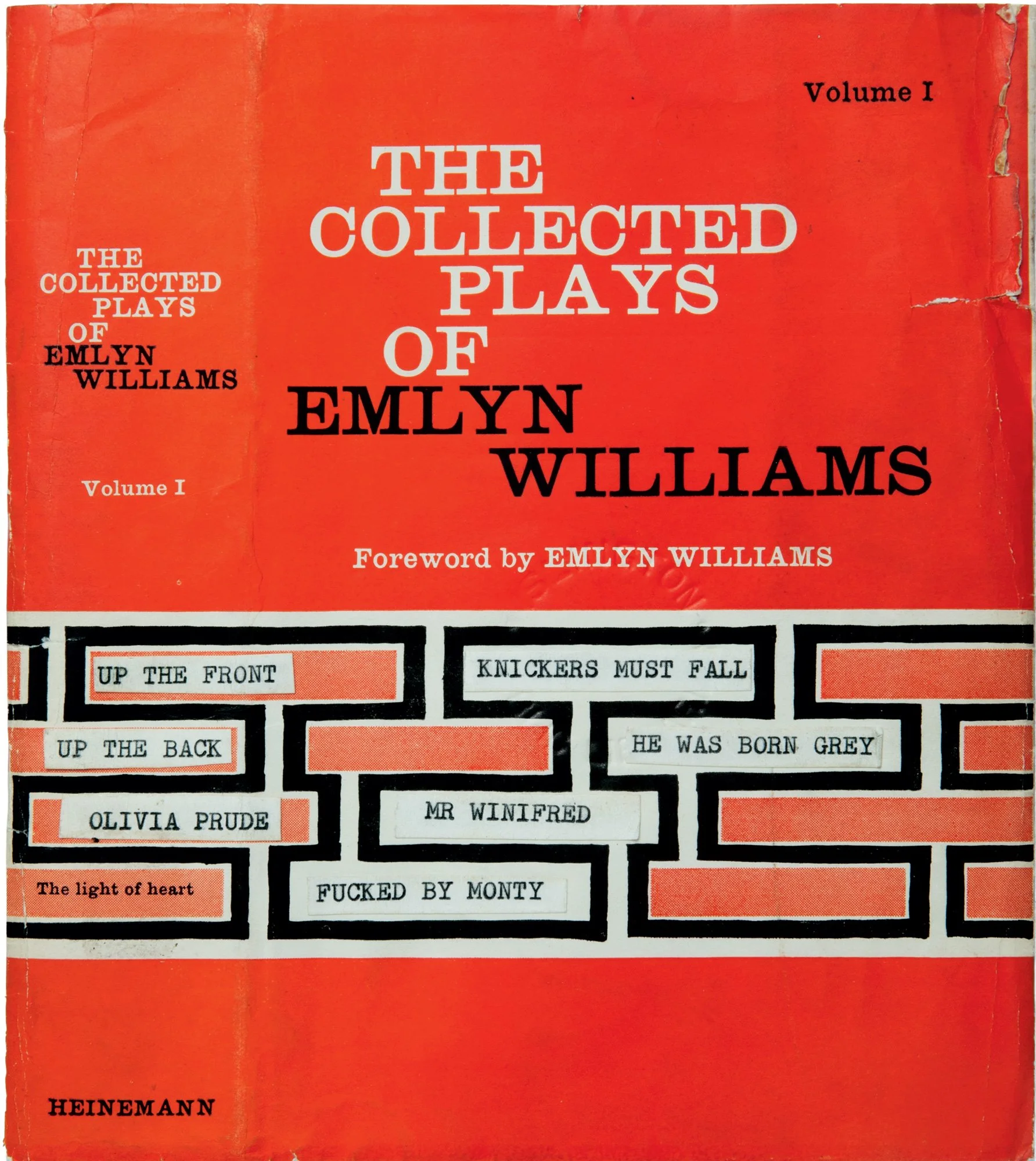

Playwright Joe Orton, alongside his boyfriend Kenneth Halliwell, devoured public library volumes, not just in reading them, but mischievously, and inventively defacing them, from 1959 for several years in the Islington area of London, and was fined and imprisoned for six months, perhaps given a stiffer sentence because of their homosexuality which was still illegal at the time. Orton, for example, took volume of poems by Poet Laureate Sir John Betjeman and returned it to the library with a new dust jacket featuring a photograph of a nearly naked, heavily tattooed middle-aged man. Disgraced for this sort of thing at the time, because of his fame, examples of it are now prized historic assets for public display. Here are a couple of examples.

Two volumes mischievously defaced by avid library visitor and famous playwright Joe Orton

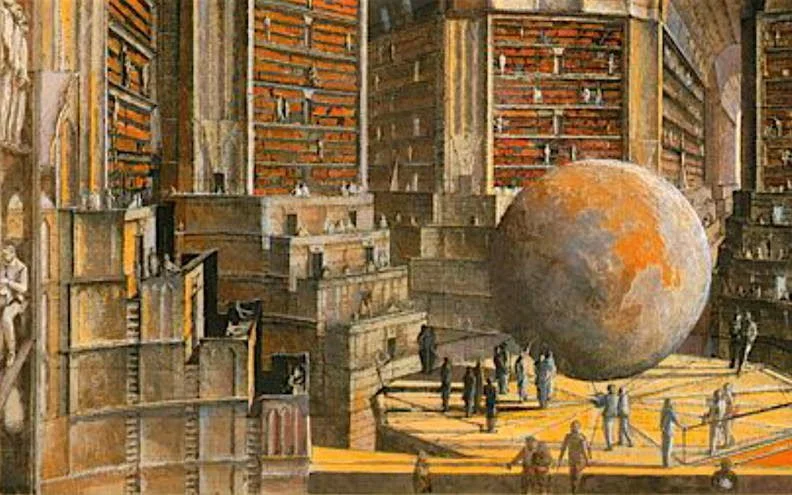

Libraries have also been the inspiration for many books themselves, such as Jorge Luis Borges’s The Library of Babel, imagining an infinite library containing every book ever written and every book that might be. It’s made up of interconnected hexagonal rooms, all identical and containing standardised bookshelves and randomised books in which some are gibberish, others not. Titles include: “Everything: the minutely detailed history of the future, the archangels’ autobiographies, the faithful catalogues of the Library, thousands and thousands of false catalogues, the demonstration of the fallacy of those catalogues, the demonstration of the fallacy of the true catalogue, the Gnostic gospel of Basilides, the commentary on that gospel, the commentary on the commentary on that gospel, the true story of your death, the translation of every book in all languages ….”

Voluminous possibility: from the cover of Jorge Luis Borges’s The Library of Babel

Libraries are imagined not merely as finite collections, but ones that are living, breathing entities. Terry Pratchett conceives of a library in which books are written themselves. In the 17th century John Donne’s Catalogus librorum aulicorum incomparabilium et non vendibilium, or The Courtier’s Library of Rare Books Not for Sale includes all kinds of imaginary titles, such as Hoby’s Afternoon Belchings and Luther’s On Shortening the Lord’s Prayer – and ironic tilt of pseudo-wisdom at courtiers. Rabelais also wrote an imaginary catalogue that wonderfully includes titles such as The Codpiece of the Law, The Testes of Theology and Martingale Breeches with Back-flaps for Turd-droppers.

This idea of infinite possibility is another key idea in library culture that may shape songs too, almost to a form of divination. This also inspired Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose set in a Benedictine monastery, The Citadel Library in A Song of Ice and Fire by George RR Martin, televised as A Game of Thrones, in which knowledge is used to fight the army of the dead.

Libraries then but keep fighting for their own survival, but how can we bring them to life in song? As settings for romance, for discovery of knowledge, or other metaphorical or literal borrowings, thefts or returns? Not wishing to direct your browsing, I’ll not start with any specific examples, but as this all began with a local library anecdote, a frivolous yet serious, and entertaining cover version of a certain Gloria Gaynor hit, rewritten to fight for the library’s survival by a group of librarians in Rappahannock, Pennsylvania, USA. More than a bit cheesy and cringeworthy at times, but also admirably well-worded and very worthwhile. Long may they survive:

So then, it’s time to grab your library card and start taking items out as well as returning them to our shelf of comments below. This week’s chief librarian, eager to stamp your ticket and check your lending history is the excellent global-spanning Loud Atlas! Deadline for returns is Monday at 11pm UK time BST, for playlists published next week. It’s time to get browsing.

New to comment? It is quick and easy. You just need to login to Disqus once. All is explained in About/FAQs ...

Fancy a turn behind the pumps at The Song Bar? Care to choose a playlist from songs nominated and write something about it? Then feel free to contact The Song Bar here, or try the usual email address. Also please follow us social media: Song Bar Twitter, Song Bar Facebook. Song Bar YouTube, and Song Bar Instagram. Please subscribe, follow and share.

Song Bar is non-profit and is simply about sharing great music. We don’t do clickbait or advertisements. Please make any donation to help keep the Bar running: