By The Landlord

"A preacher must be both soldier and shepherd. He must nourish, defend, and teach; he must have teeth in his mouth, and be able to bite and fight." – Martin Luther

"Love is the only weapon with which I've got to fight. I've got a hell of a lot of weapons to fight! I've got my claws. I've got cutlasses. I've got guns. I've got dynamite. I've got a hell of a lot to fight! I'll fight! I'll fight!" – Rev. Jim Jones

"To be a preacher requires two apparently contradictory qualities: confidence and humility." – Timothy Radcliffe

"One preacher turned me on, another turned me off." – Barry White

"Preachers denounce sin as if it was available to everyone." – Frank Dane

“The only people who like to live alone more than comics are priests.” – Colin Quinn

"Who will rid me of this troublesome priest?" - King Henry II on Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket

"That money was just resting in my account!" – Father Ted Crilly

Pulpit pontificators, grey-day lightning-conductors of belief, hands-laying, prayer-whispering, fear-flame-throwing proclaimers? Preachers can be all things to all people. They might be mesmeric, magnetic, inspirational, charismatic, intelligent, forceful, driven, perceptive, persuasive, and natural-born leaders.

Their presence might span entire lives of communities, from smiling down on screaming newborns, to blessing hopeful, happy couples, receivers of secrets as they bend a fascinated ear to distraught confessors, and then ultimately are magnets to the sick and dying, like clever, but comforting last-rites crows quietly approaching an impending carcass. They are shepherds and exploiters of the flock, sometimes saviours of our souls, sometimes total arseholes.

Heroes to some, and villains to others, religious preachers, ministers, priests and the like could be described as soundtrack performers to ordinary lives, some even arguably the past's rock and pop stars before that form of music even existed.

Saxophonist Clarence Clemons captures that crossover with this remark: “Rock-and-roll, to me, is very serious because we deal with the young people. We deal with people who need something, and that's the same thing that a preacher does. He feeds you something that you need spiritually in your soul and in your makeup.”

And here’s Curtis Mayfield: “With all respect, I'm sure that we have enough preachers in the world. Through my way of writing, I was capable of being able to say these things and yet not make a person feel as though they're being preached at.”

And in another genre, here’s the revered conductor Simon Rattle: “We have to be evangelists for music. We couldn't just be high priests of music.”

The church, and other religious institutions, after all, have been the cradle for so many musicians to first learn their craft, especially those of the gospel and evangelistic variety. But like such performers and life accompanyists, preachers are not divine, and far from perfect, but deeply flawed, human, complex, secretive, variously greedy and generous, contradictory characters, wrought with as many weaknesses as strengths. And they no doubt suffer inner torment from the strains of keeping up a public face, and can be as much a force of harm as well as good. All of which makes them a fascinating subject for song.

So this week we're looking for songs primarily about, or in which these figures play a key role, from priests, popes to preachers, ministers, bishops, deacons, vicars, reverends and clerics, curates, clergymen or clergywomen, and not just figures of of the Christian faith, but also imams, rabbis, ayatollahs, pujaris or any other type formally chosen to lead society's moral high ground in the name of god.

When Henry II's hypothetical remark was taken literally by four nights who rode to Canterbury Cathedral in 1170 to mercilessly hack a robed Thomas Becket to bits at the altar, leading to the king's ultimate shame and remorse, it was part of long history of deeply troubling times for church and state, the archbishop having been a staunch critic of the monarch meddling in religious affairs in confusing time over respective roles. Perhaps that sums up huge dilemma what preachers are for - moral or earthly matters, and when the two get mixed up, that's when there are problems.

This is a subject touched upon by religious figures of all types, good and bad often in contradiction. “Preachers are not called to be politicians but soul winners,” proclaimed Jerry Falwell, the controversial right-wing bible-bashing American Baptist pastor and televangelist and conservative activist, who despite what he said, had no qualms about wading into many matters, including declaring the sins of homosexuality.

Meanwhile the Reverend Al Sharpton, hero of the civil rights movement, declared that it’s impossible not to become involved in social matters: “As a preacher who has spent significant time in churches and houses of worship all across the country, I can tell you firsthand that religious liberty and freedom are principles that can never be infringed upon.”

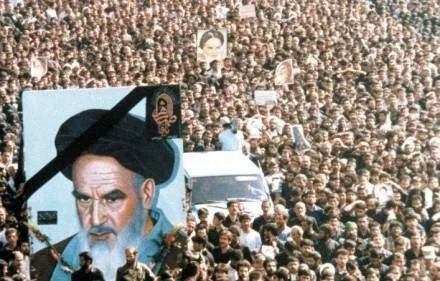

In a different way, that’s certainly a philosophy followed by Iran’s religious leader and revolutionary Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, but his 1989 funeral turned in a frenzied chaos:

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini;s funeral

Yet while history has seen preachers receiving mostly reverence, critics of the clergy are also nothing new. Diogenes wrote that: "When I look upon seamen, men of science and philosophers, man is the wisest of all beings; when I look upon priests and prophets nothing is as contemptible as man."

As Samuel Butler put it: "Priests are not men of the world; it is not intended that they should be; and a University training is the one best adapted to prevent their becoming so."

Thomas Paine, author of The Age of Reason, was also no fan of the clergy. "One good schoolmaster is of more use than a hundred priests," he wrote. And: "That God cannot lie, is no advantage to your argument, because it is no proof that priests can not, or that the Bible does not."

It's likely that good priests are far less likely to make headlines and songs that bad ones, and who remembers the good popes, after all? It's figures such the bad boys of the Vatican who make for the sexier stories, such as Pope John XII (955–964), who gave land to one of his many mistresses, murdered several people, and then was killed by a man who caught him in bed with his wife. What a rotter.

Or how about arch-torturer Pope Urban VI (1378–1389), who complained that he did not hear enough screaming when Cardinals who had conspired against him were put on the rack or other nasty dungeon devices? Not to mention of course, the various Borgias, such as Alexander VI (1492–1503), an outrageously corrupt nepotist who met with an untimely end and whose unattended corpse swelled until it could barely fit in a coffin. The Catholic Church is perhaps the leading breeding ground of greedy corruption, sex scandals, child abuse and much more.

Bad boy Pope Alexander VI Borgia

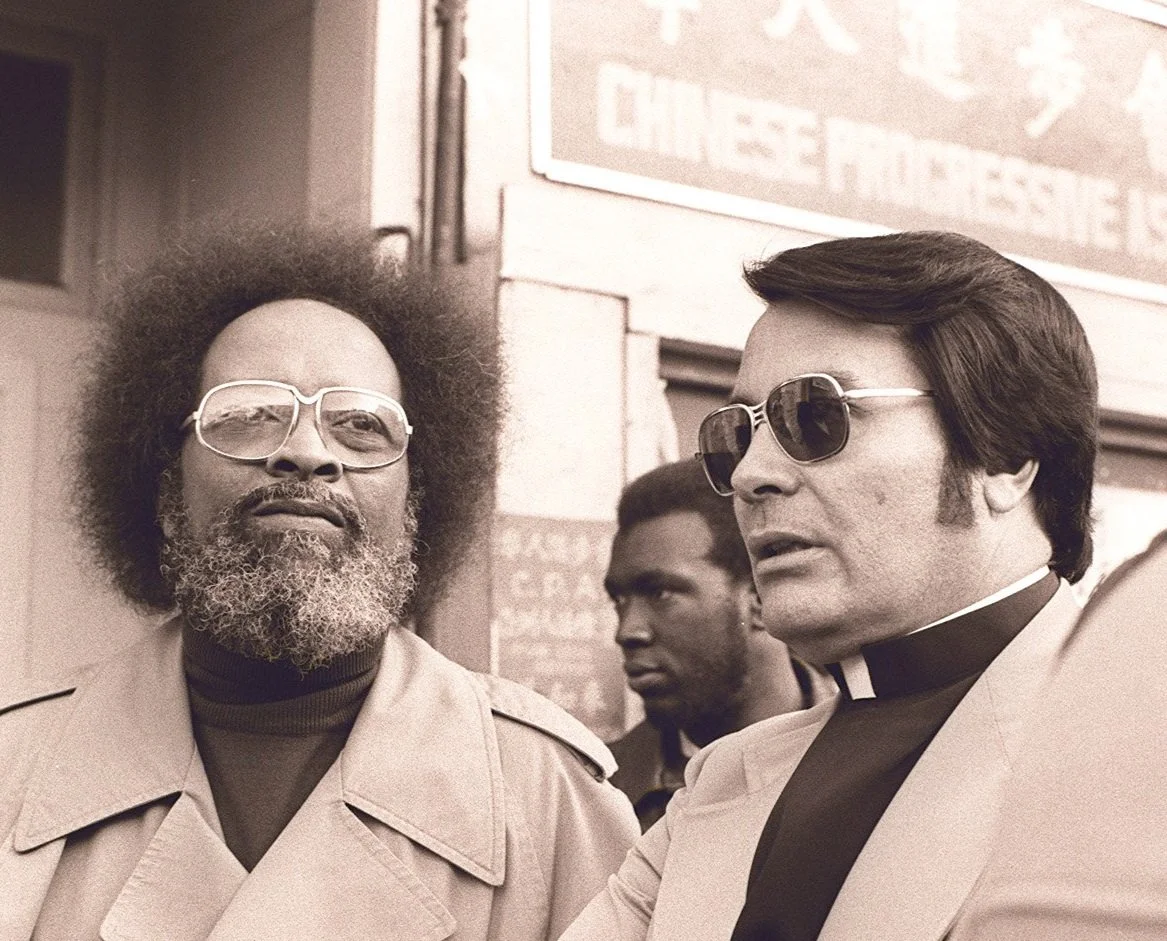

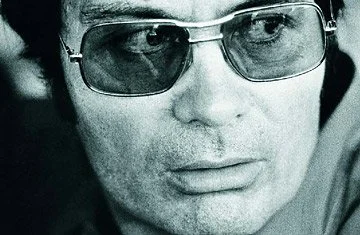

But perhaps is the more recent religious leaders who may attract song attention, not least those who stray into extreme controversy. James Warren Jones (13 May 1931 – 18 November 18 1978), better known as Jim Jones, was an extraordinary figure, highly intelligent, ambitious, fighting many social justice causes, a Pentecostal minister who formed his own church, the Peoples Temple, and adopted many children from different backgrounds into his “rainbow family” but got entwined in huge amounts of financial corruption, violence, murder, drug-taking, ultimately enslaving his followers for sex and other duties in his cult Georgetown settlement in Guyana, culminating in that infamous mass murder-suicide event in 1978 in which he also died. He was a man described succinctly by David Nemer as: “A paranoid narcissist, enthralling, persuasive and power-hungry. He thrived on attention, adoration and adulation. He was equal parts bully and charmer.”

Jim Jones in a rarely seen pensive moment …

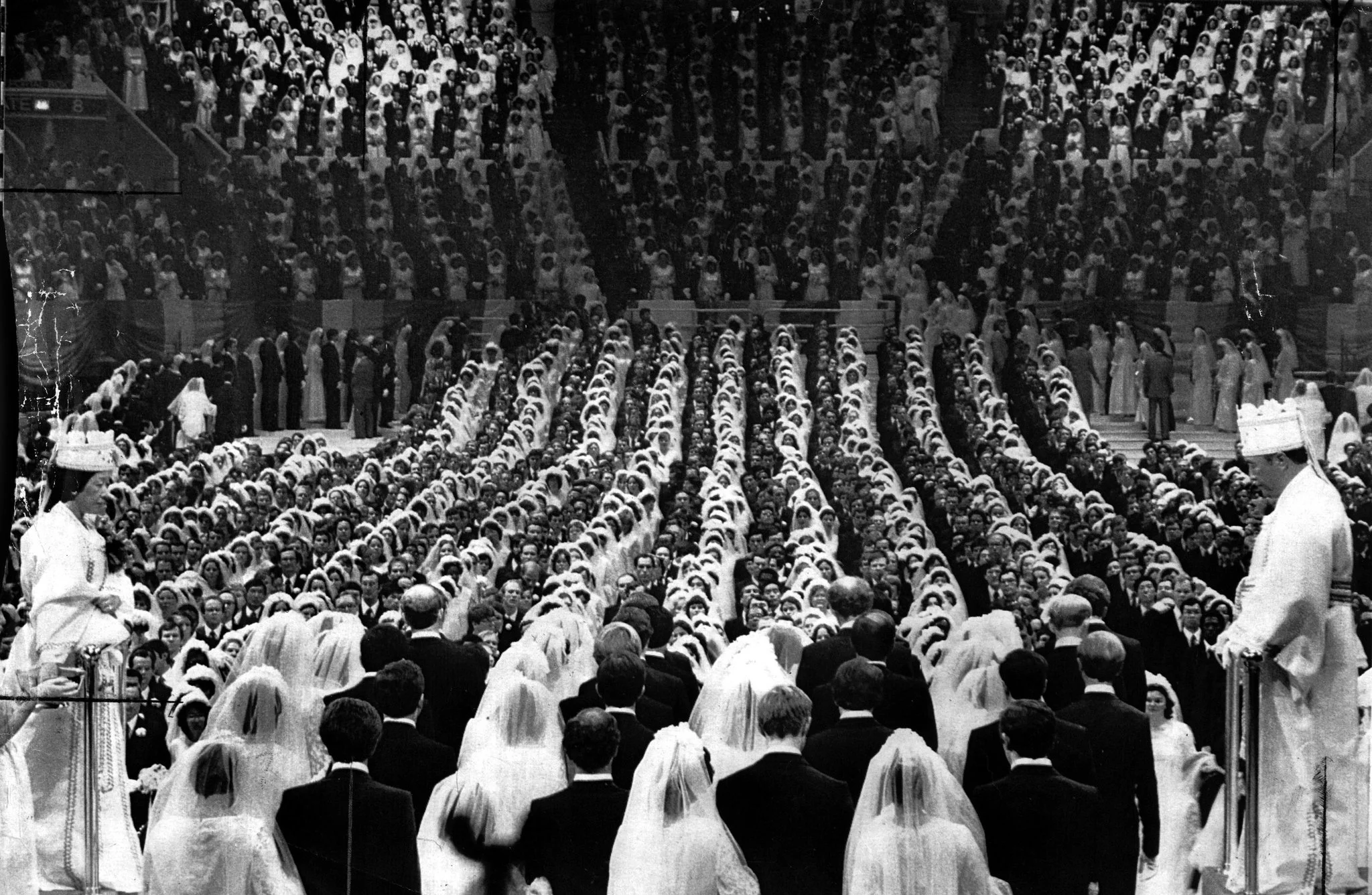

At this point we could get pulled into the topic of cults, one that is perhaps best left for another time, especially when it comes to figures of personality such as Charles Manson, but then again as they are forms of quasi-religious leaders, there may also be room, if song-relevant for numbers pertaining to figures such as the Jaimie Gomez and Buddhafield, Heaven’s Gate leader Marshall Applewhite, Shoko Asahara, who built the doomsday cult Aum Shinrikyo, or the controversial but eventually doomed Bhagwan Shri Rajneesh and followers, or the ongoing successful Sun Myung Moon, who transformed the Unification Church into a still-thriving economic machine with a particular penchant for mass weddings All extraordinary people, they all set out as preachers or spiritual leaders of a kind, but then became something else entirely.

Sun Myung Moon (right) conducting one of many mass weddings

As author Neil Postman put it: “Our priests and presidents, our surgeons and lawyers, our educators and newscasters need worry less about satisfying the demands of their discipline than the demands of good showmanship.”

But to get an insight into the mind of a preacher, perhaps it’s also fun to dip into some fictional examples in books, film and TV, that in turn have inspired song.

George Eliot captures public-private divided mind of preacher perfectly in the novel Romola: “His faith wavered, but not his speech: it is the lot of every man who has to speak for the satisfaction of the crowd, that he must often speak in virtue of yesterday's faith, hoping it will come back to-morrow.”

And in another great literary work, there’s a wonderful depiction of all the subtle nuances of the clergy in all their weakness and strengths. Perhaps within it does the most memorable character is the scheming underling in a lowly curate. As I’ve written before, unlike in the violent tales of religious leaders in America or other parts of the world, in this 19th-century setting, no one dies, except in old age. No violence occurs, aside from a sudden slap to the face. But something truly evil lurks in sleepy, leafy Barchester. It begins with a creeping sense of dread. Then comes a remorseless feeling that one’s livelihood, and everything on which it depends, could be entirely controlled by someone who has no interest in your welfare and cares only to better their own position. Sounds exactly like a modern-day Tory. This may sound like very contemporary villainy, but there are few more dangerous baddies than the ambitious, ever-plotting, slimy Obadiah Slope, the calculating curate who sends shockwaves of unease through the diocese of Anthony Trollope’s Barchester Towers.

Slope has an instantly unsettling physical presence. “His hair is lank, and of a dull, reddish hue, lumpy masses, cemented with much grease.” He is “saucer-eyed”. “His face is not unlike beef of a bad quality. A cold, clammy perspiration always exudes from him, the small drops are ever to be seen standing on his brow, and his friendly grasp is unpleasant.” But such things are only skin deep. It is Slope’s methods that cause greatest recoil. And every tiny detail of his character was wonderfully captured in a BBC adaptation in a performance by a youngish Alan Rickman:

Alan Rickman as Barchester Tower’s calculating curate Obadiah Slope

Another brilliant performance of an even dodgier preacher type, one at the centre of perhaps my favourite film is Robert Mitchum in Charles Laughton’s singular unsung masterpiece, 1955’s Night of the Hunter, a figure who fools almost everyone in his pursuit of stolen money in the hands of two orphans, first murdering their mother, but not before explaining how he is on the side of good over evil with his tattooed knuckles showing Love and Hate:

Another powerful film, The Apostle (1997) with Robert Duvall, follows an charismatic Evangelist preacher who loses his way. In a jealous rage he kills his wife’s lover, and then escapes to another community and sets up a new church before his past catches up on him. Duvall was inspired to make the film in his research: “I love going to black churches, and I love some of these black preachers. The best preacher I ever saw in my life was a 93-year-old in a black church in Hamilton, Virginia. What a preacher!”

But Duvall’s character is deeply flawed, a tough man channelling god but trying to do good. Here are a couple of clips, first in the throws of religious zeal but still troubled, and then tackling a racist interloper played by Billy Bob Thornton:

Perhaps one of the most passionate performances by and about a priest as much comes in David Milch’s superb TV drama Deadwood, set in the gold rush of Dakota and entirely based on real characters from the late 19th century. The town’s pastor, Reverend Smith (Ray McKinnon), dies a long, slow, painful, lingering death, but the best performance comes from Brad Dourif who plays the town’s doctor, who rages at god about the injustice of the good man’s suffering, in a Shakespearean monologue recalling his experiences as a civil war surgeon. All this then, before ruthless bar owner and town hardman Al Swearengen, played incomparably Ian McShane, comes to offer the priest some merciful last rites of his own.

But to lighten things up a bit, surely there is no more entertaining depiction of the priesthood than the 1990s sitcom Father Ted, set on the fictional Irish Craggy Ireland, a superbly timed comic satire of all the flaws of the profession, one that an Irish friend of mine wryly says is “less a comedy, more a documentary”. Ted is depressed man trapped in his profession, surrounded by all types, from the stupid to the mad, the thick Father Dougal to the angry alcoholic Father Jack to the crazy housekeeper, and there are many great supporting roles such as the dancing priest, the boring priest, the evil priest and the scary Bishop Brennan. There are far too many magical moments to do it all justice but here are a few:

There’s plenty of dark sides to preachers and priests, but for balance, let’s end on a more positive note. The great Maya Angelou credits much of her to a certain type. “I find in my poetry and prose the rhythms and imagery of the best - I mean, when I'm at my best - of the good Southern black preachers.”

We began with a quote by Martin Luther, but talking, as Maya does of the best, let’s end with that speech by Dr Martin Luther King Jr. Look at the faces of the crowd …

So then, it’s time for you to sermonise with your songs on this subject. Following the potent and powerful topic of shame a couple of weeks ago, sorting out the good from the bad, this week’s high priest of playlists sees the return of the ever diligent DiscoMonster! Place your preacher-related songs in comments below, in time for end of service at 11pm UK time on Monday, for playlists published next week. It’s time for some divine, as well as earthly inspiration …

New to comment? It is quick and easy. You just need to login to Disqus once. All is explained in About/FAQs ...

Fancy a turn behind the pumps at The Song Bar? Care to choose a playlist from songs nominated and write something about it? Then feel free to contact The Song Bar here, or try the usual email address. Also please follow us social media: Song Bar Twitter, Song Bar Facebook. Song Bar YouTube, and Song Bar Instagram. Please subscribe, follow and share.

Song Bar is non-profit and is simply about sharing great music. We don’t do clickbait or advertisements. Please make any donation to help keep the Bar running: